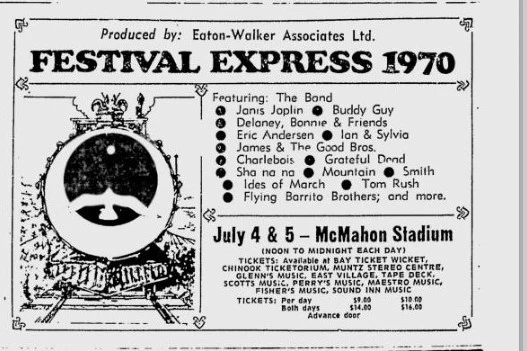

Editor’s note: Fifty years ago tomorrow, a trainload of famous rock, blues and country stars rolled into Calgary for one of the most unique music festival experiences ever…The Festival Express. The article below focuses mainly on the Calgary stop of the festival. Along with rare archival photos, we’ve included likely never-before-seen surveillance video of the festival from the skies above McMahon Stadium.

Written by: Ron Kelland and Jared Majeski, Historic Resources Management Branch

The 1970s were a good time for the City of Calgary. People came in droves to call Cowtown home, as its population increased by a third. Construction permits rained down like confetti as the city’s skyline shot mightily to the heavens. The famed Husky Tower (now simply known as the Calgary Tower) had recently been completed, giving Calgary’s skyline a truly distinctive look and providing a symbol of civic pride and optimism for decades to come. The famous, architectural award winning +15 Skyway pedway system, one of the most extensive systems in the world, was constructed and plans for a new and innovative urban transportation network, including the Deerfoot Trail freeway and what would become the LRT/C-Train system, were underway.

This is what Albertans call, “the good times”, the boom of our familiar economic cycle. Perhaps it was this optimistic feeling that convinced the city to approve a permit to host a now-infamous, “rock music festival” at McMahon Stadium in early July.

South of the border, tensions were, to put it lightly, running high. More and more citizens saw the Vietnam War as a failure; protests erupted throughout the country. In August 1969, the great music festival at Woodstock, NY used music to give an immutable voice to the hopes and fears of a generation of disaffected young people. That voice that was just as quickly threatened by violence in December of that year at the disastrous music festival at the Altamont Speedway in California, and, in May 1970, at Kent State University in Ohio, when National Guardsmen shot and killed four anti-war protesters. Youth in North America were increasingly fed up with it all—the war, the system, the man, the corporations, the economic system, their elders and their government. This dissatisfaction was voiced in an increasing number of protests, but it was also expressed through music, concerts and festivals.

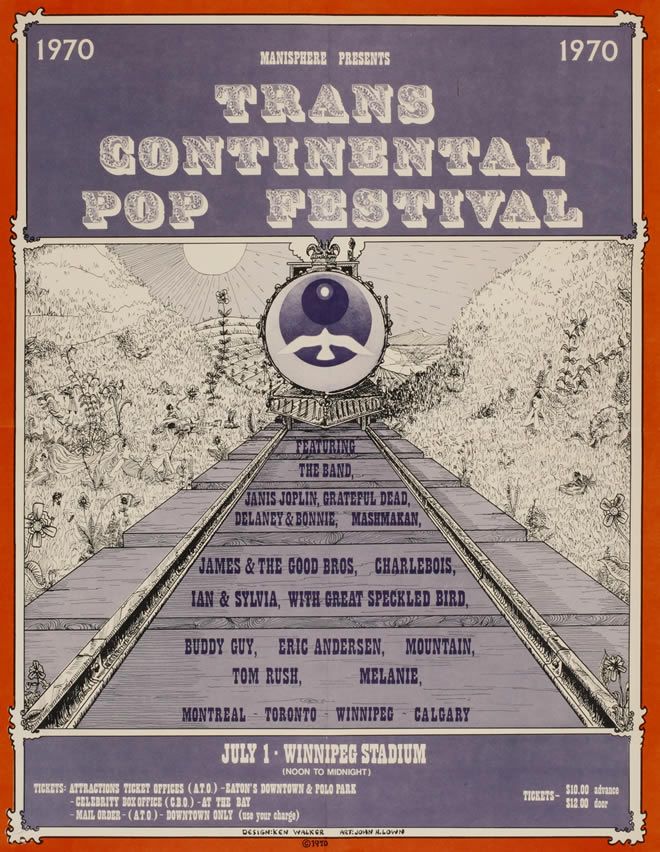

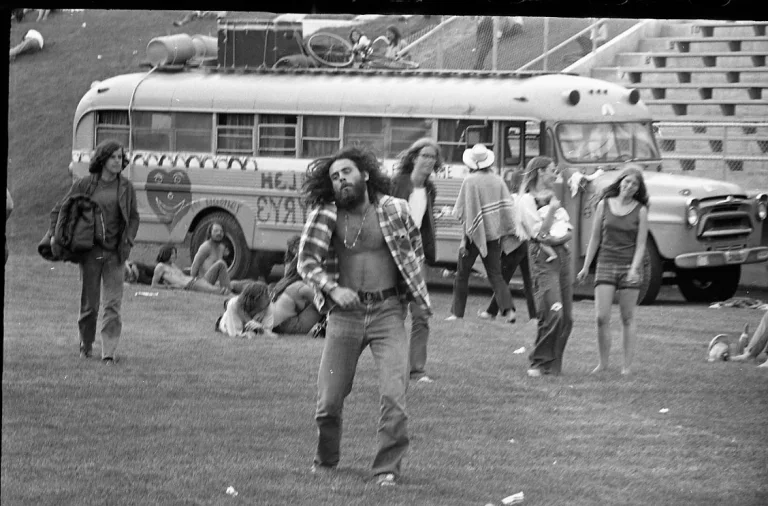

It’s in this context that we are going to examine the famous Festival Express, a musical experience that still stands unique even as the “music festival” is now so ubiquitous in our culture. Take the biggest rock, blues and folks stars of the time, put them on a train (with plenty of music and “good times”) and have them play to festival-sized crowds as they trundle west through Canada: that was the concept of Festival Express.

Created by a young 20-something promoter named Ken Walker, the idea was as bold as it was a financial ruin for many involved. Thankfully, despite the riots, cancelled gigs and physical confrontations with elected officials, a film crew was there to document the entire proceedings. What you ended up with, the documentary Festival Express, wouldn’t be seen by the public until 2003. Directed by Bob Smeaton, the film stars the aforementioned Walker along with The Grateful Dead, The Band, Janis Joplin, Flying Burrito Brothers, Buddy Guy and Ian and Sylvia Tyson, just to name a few. While most festivals see artists and bands part ways after their gigs, Festival Express ended each night with everyone piling onto a chartered Canadian National Railways passenger train where they partied all the way to the next stop. When all was said and done, the festival ended up playing only three stops: Toronto, Winnipeg and Calgary, and helped create a generational and national experience along the way.

Toronto and Winnipeg

An opening show was planned for Montreal on June 24, but the City of Montreal cancelled the event as it conflicted with plans for the annual St. Jean-Baptiste celebrations. So, the Festival Express opened its first show in Toronto on June 27.

The events at Kent State a couple months earlier led to violence and protest at the first stop of the Festival Express tour in Toronto. A protest group demanded that the concert be free; the price for a ticket was, at the time, an outrageous $14 (about $95 in 2020). The protesters tried to force their way through the gates, leading to a number of injuries to protesters and police officers. To placate the crowd, Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead worked with the Toronto police to stage a free ‘rehearsal’ concert on the back of a flatbed truck in a nearby park. With the protest diffused, both the free concert and the official show continued. An estimated 37,000 attended the show with up to 6,000 attending the free concert.

Given the scene at the Toronto show, police, promoters and the artists were eagerly waiting to feel the vibe of concertgoers at the Winnipeg stop. In the end, the event went off without much of a hitch. Attendance, at only 4,600, was much lower then anticipated, but everyone seemed to have fun.

Calgary

The Festival Express was originally planned to wrap up with a show in Vancouver, but scheduling conflicts at the Pacific National Exhibition Stadium resulted in a last-minute search for a new venue in the city. But it was all for naught as the City of Vancouver refused the event a permit over concerns about inadequate sanitation facilities and security. With Vancouver out of the picture, at the last minute, Calgary was added as the final stop on the tour with a July 4th and 5th show at the then 10-year old McMahon football stadium, located on the University of Calgary campus out on the northern edge of the city.

As the promoters were seeking a permit for the concert in Calgary, the Calgary Police Service sent a letter to Mayor of Calgary Rod Sykes expressing their concerns about the proposed concert. The Calgary police noted that the police service would be faced with an untenable decision to either enforce the law, potentially prompting a violent reaction from concertgoers, or permit a certain amount of lawlessness to occur, which could upset other citizens.

The Calgary Police Service was very concerned, “that the experience of other cities was one of tremendous public resentment, depreciation of the police image because of the impossibility of coping with the resultant flagrant breaches of the law.” Furthermore, the chief medical officer condemned the proposed concert saying that, “[t]hese music love-in festivals are generally only attended by hippies and the oddballs of society and create nothing but serious problems…to say noting of crime and general disorder. Everyone is certainly resolved to discourage any plans for such an event in this region.”

In a biography of Rod Sykes, journalist Andy Marshall notes that Mayor Sykes vehemently overruled all of these objections, stating that, “In no way does this administration support the expression of only negative, destructive, contemptuous, and antagonistic attitudes towards any group of people in this community. All have the same rights, and those rights will be respected.” With the support of the mayor’s office, city administration approved the event. Mayor Sykes further said that the festival and any future similar events would, “be treated with complete courtesy and the fullest co-operation” and that he expected the police to handle the situation in a professional manner.

It also probably helped that Sykes Executive Assistant and advisor Mike Horsey, saw the concert as an opportunity for Calgary to begin to shed its image as a backwater town and start to develop as a cultural center. Promoter Ken Walker acknowledged that the festival wouldn’t have come to Calgary, “had it not been for the encouragement in and around City Hall,” which is a bit of an ironic statement considering how events later unfolded between him and the mayor.

The Festival Express train pulled into Calgary, after a stop in Saskatoon to replenish the liquor supply. That first night in Calgary saw a number of the Festival Express artists exploring the city and getting into some shenanigans, some voluntary, some less so. Janis Joplin allegedly flashed her tattooed breasts at a Calgary Herald reporter and photographer, exhorting him to, “take a picture of these!”.

Ian Tyson was at that time part of the duo act Ian & Sylvia and the Great Speckled Bird. He had not yet acquired his ranch in the Longview area and had still to fully cement his reputation as one of Alberta’s premier singer-songwriters. Outside the Cecil Hotel in downtown Calgary, he was jumped in an attempted mugging. In his memoirs, Tyson recalled breaking his hand on the assailant’s skull and having to fight through the pain to perform the next day. James Good of The Good Brothers told a reporter that a few of the performers had made a run out to Banff for the day where they hiked up Mount Norquay and that the police had stopped them on way. According to Good, the performers played a few tunes while the officers were searching for drugs and that the cops and the performers had all parted on good terms.

In a less dramatic, but just as delightful story, Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead found his way to a free music festival on Prince’s Island Park that had been organized by local promoter Gerry Sylvan to feature nine local bands and one from Montreal. While under contract to the Festival Express tour, Garcia was not able to perform on stage, but he mingled with the crowds and audience and commented to Calgary Herald reporter Peter Leney, “This is more of a festival than tomorrow’s is going to be. Tomorrow is just going to be a gig – another concert.”

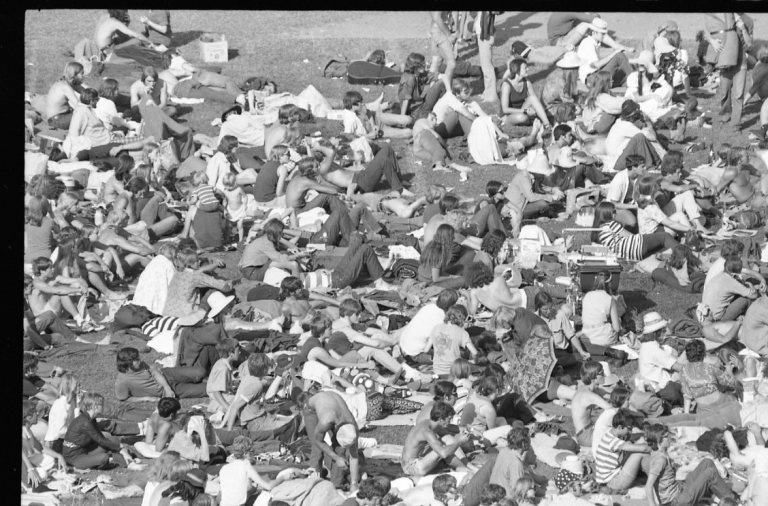

With the free concert being held on Prince’s Island, and with the official Festival Express show happening in the following days, Calgary found itself filled with youth from all around. A campground sprouted up and the Bow River became a large communal, clothing optional swimming and washing area. Volunteers organized food drives to keep the festival attendees fed. The City of Calgary, in a magnanimous gesture, granted the festival use of Prince’s Island for the concert and campground, all free of charge.

In the words of that same Herald reporter, “Prince’s Island was liberated. And in the minds of many people in the audience, Calgary’s image was changed drastically for the better.” Upon observing the events on Prince’s Island, one older Calgarian, who described herself as, “being a bit prejudiced” about the idea, conceded that everyone seemed to be very well behaved and added that it would be a real tribute to Calgary if both the Prince’s Island festival and the Festival Express concert at McMahon Stadium were pulled off with no trouble or violence. Her hopes would be prophetic.

Back at McMahon Stadium the following day, the festival promoters, the Calgary Police Service and Mayor Sykes were preparing for the shows. Having had their concerns about the show and the potential for violence dismissed, the Calgary police geared up for the show. Despite a failed attempt to mobilize the militia as a security force, the police were still arguably over-prepared. The chief of police had readied the riot squad, and secretly stationed them at the Sarcee Barracks a short distance away.

Mayor Sykes had apparently not completely dismissed the concerns of the police service, likely hoping to forestall the protests over ticket processes that had ignited the violence in Toronto. Mayor Sykes even tried to convince promoter Ken Walker to allow people in for free. Walker disagreed and the argument got heated. According to a police officer that witnessed the altercation, Sykes demanded that Walker be arrested and Walker threatened to sue the mayor and the city. Walker recalls that he ended the argument by punching Mayor Sykes in the face. The officer on the scene recalled that Walker’s swing missed and hit a garbage can instead.

The potential of drug use and medical issues arising from drugs was also a concern. In April 1970, the Drug Information Centre (DIC), know known as the Distress Centre, was established in Calgary to educate people about drugs and to provide medical assistance and counseling services for people with drug addictions. The DIC approached concert organizers and, with their co-operation and support, established a first-aid, treatment and recovery site near McMahon Stadium. Known as “Tranquility Base” the DIC centre was staffed primarily with volunteers, including three doctors. Over the two day event, Tranquility Base treated 155 patients, about half for general injuries and half for drug-related issues.

Editor’s note: To get the full experience, put on your favourite Grateful Dead or The Band song before playing this video.

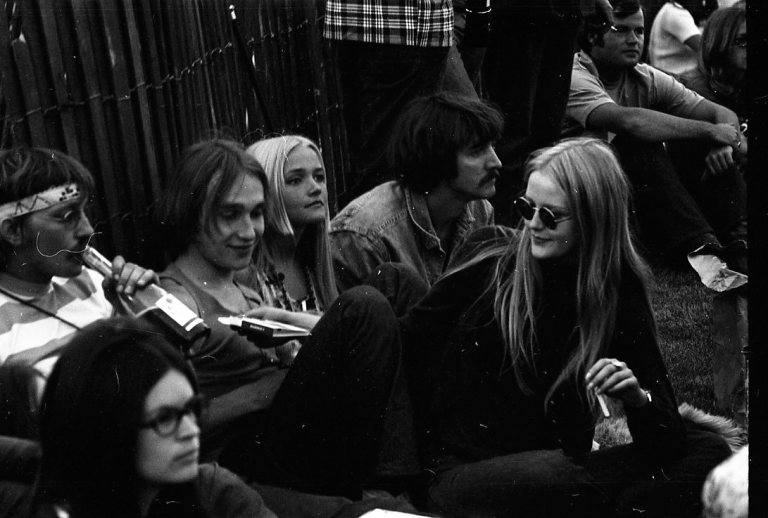

Whatever was going on behind the scenes, the concert itself was a spectacle to behold. An exact line-up of the concert order and set lists is difficult to determine, but some idea of the line-up can be derived from newspaper coverage of the show and film footage later released in a documentary about the tour. In a short review of the two-day event by Bill Mussellwhite of the Calgary Herald, we know that Sha Na Na performed “Rock and Roll is Here to Stay”. A local group, Gainsborough Gallery, offered a, “hard-driving” set that more than held its own amongst the high-flying international acts.

Janis Joplin owned the Saturday concert with her electrifying performance of “Cry Baby” and “Tell Mama” in what is arguably one of the best performances of her short, but legendary career.

The Sunday show was headlined and closed by The Band, described by the Herald as, “being also Canadians” (mostly true, but Levon Helm might have had objections to that description). They performed, among many of their other classics, “The Long Black Veil”, “Rockin’ Chair” and “I Shall Be Released”.

At one point, Ken Walker and the other promoters were called to the stage, where the artists presented Walker with a model train and a plaque honouring his dedication to making the tour happen. Joplin also personally presented him with a case of tequila.

Mayor Sykes, who had clashed with the Calgary Police Service about the concerts and who would continue to have a tempestuous relationship with police service throughout his tenure as mayor, himself praised the officers for their exceptional conduct during the event. A child psychiatrist interviewed by the Herald about the event enthused, “It’s just like a great big picnic. People are flying kites, throwing frisbees and running around. I can’t understand what all the fuss was about beforehand.”

The Aftermath

The Producers and the Performers

The Festival Express tour may have been a cultural milestone for Calgary and a good time for those that performed and attended, but it was a financial failure for its promoters. Ken Walker later said that if given the opportunity he would never embark on such a project again. For the performers, however, Festival Express was an experience that the artists enjoyed and appreciated. Jerry Garcia recalled that unlike most concerts and festivals, where artists show up, play their sets and leave, never having the opportunity to enjoy each others company, the Festival Express experience of a week all traveling together on a dedicated train gave these artists a rare opportunity to play together, to talk and to collaborate.

Ken Walker had ensured that the train was equipped with sound systems so that the artists could jam. The result was once-in-a-lifetime jam sessions with legendary artists of different styles and genres. Janis Joplin told a Herald reporter that it was the best party that she had ever been to.

The Morrow Report

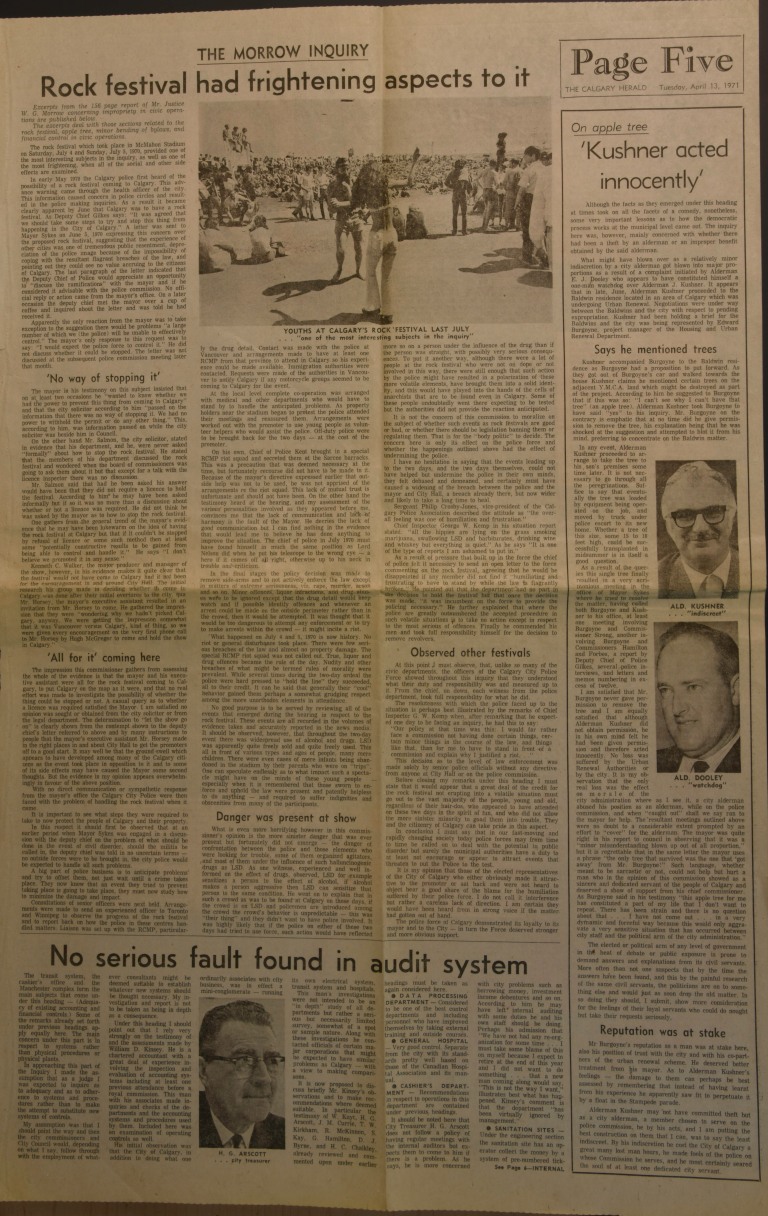

The festival had some less joyous fallout as well. Prior to the concert and quickly after his election to the mayor’s office, Rod Sykes had pushed for an inquiry into allegations of corruption and theft from the city’s transit service. Largely at the mayor’s insistence, the city requested that Justice W.G. Morrow of the Northwest Territories Supreme Court conduct an investigation into the matter. The Morrow Report, released in 1971, roundly condemned Calgary city administration for its cavalier use of transit revenues. However, Morrow’s investigation had also expanded to looking at the deteriorating relationship between the Mayor’s Office and the police service, specifically in regards to police service’s handling of the Festival Express concerts.

The Morrow report starts by making note the dismissal of the police service’s concerns by the Mayor’s Office. Morrow also concluded that a number of laws were broken at the concert, notably that, “liquor and drug offences became the rule of the day,” that, “nudity and other breaches of what might be termed rules of morality were prevalent” and that there were reports, “of mere infants being abandoned in the stadium by their parents who were on ‘trips’.” However, Morrow also noted the significance of the fact that the concert went off without any notable violence or criminal activity, concluding that, “It can be said that generally their [police] ‘cool’ behavior gained them perhaps a somewhat grudging respect among the more unorthodox elements in attendance.”

In the end, the performers dispersed with the high of a joyous and music-filled party still fresh in their minds. The promoters licked their wounds and moved on to their next projects. The police and politicians faced a mixture of adulation and criticism over the handling of the event. But perhaps the best summation of the Festival Express was offered by Bill Musselwhite of the Calgary Herald who signed off his July 6, 1970 review of a show that Calgary had never seen the likes of before, saying:

“It was a two-day high in a different world, a remarkably good world. That’s what mattered.”

Editor’s note: If anyone attended the Festival Express, leave a comment and share your stories! If you have photos or videos, you can send them to jared.majeski@gov.ab.ca.

Sources

“A Canadian Guide to the Festival Express 1970,” GratefulSeconds.com (blog), October 4, 2017, http://www.gratefulseconds.com/2017/10/a-canadian-guide-to-festival-express.html.

Distress Centre. “50 Stories Part 3: Sex, Drugs and Rock and Roll.” 21 January 2020. Available from https://www.distresscentre.com/2020/01/50-stories-part-3-sex-drugs-and-rock-and-roll/

Marshall, Andy. Thin Power: How Former Calgary Mayor Rod Sykes Stamped his Brand on the City…And Scorched some Sacred Cows. (Victoria: Friesens Press, 2016)

Smeaton, Bon and Frank Cvitanovich, dirs. Festival Express. 2003 (London, UK: Apollo Films & Amsterdam: PeachTree Films, 2003. Distributed by New Line Home Entertainment. DVD.

Tyson, Ian. The Long Trail: My Life in the West. (Toronto: Random House of Canada, 2010)

Excerpts from Morrow Inquiry, Calgary Herald, April 13, 1971

Calgary Herald, July 6, 1970

YouthLink Calgary Police Interpretive Centre

Thisdayinmusic.com

My sister and I were about 15 and went up there from Edmonton. We sneaked in with the Grateful Dead, who told security we were with them and got vip backstage passes. Met Janis Joplin. Had a ball.

Amazing!!

I know I was there and so were my friends but I can’t remember anything else … 🍄

I was in one of two buses (the Blue Bus seen in the video above) that traveled with the festival. Although the train couldn’t haul our buses, they paid our expenses and gave us full access. We were able to board the train at stops.Between Winnipeg and Calgary, the RCMP stopped our bus and held us in the midday sun on the side of the road for hours, while they searched our bus for non existent contraband. The best they could come up with was a 50 lb bag of brown rice, which they labeled as “corn mash” and confiscated. When we reached the next town, we called ahead to the festival, explained ourselves and asked them to make arrangements with the authorities so we we would get there on time. Arrangements were made, and when we arrived in Calgary, we were met by police motorcycle escorts. They lead us to the hotel downtown where all the performers were hanging out. After dinner with the gang, we were given another escort to the festival grounds..

It is sad that folks like , Janis Joplin and Jerry Garcia , as well as Levon Helm are no longer alive. One performer on that Festival Express that is still alive and is in the midst of His last Tour , Mr. Buddy Guy!

Whether you’re dealing with a minor injury or a major one, a Edmonton injury lawyers can help you assess your options and make informed decisions about your case.