“What is the matter with the Calgary Irishmen?” asked a frustrated correspondent to the Calgary Herald in March 1916. The writer, who identified themself as ‘F. Fitzsimmons,’ was complaining about the city’s apparent lack of enthusiasm for St. Patrick’s Day, with no public events planned to celebrate the day. Fitzsimmons conceded that people were likely distracted by the war effort, but lamented that Calgary’s leading Irish citizens had gotten “cold feet” and failed to plan any celebrations. “If all Irishmen were like the Calgary bunch” closed the writer, then “‘God Save Ireland.’”

The language used by Fitzsimmons in this letter is highly suggestive. By stating that Calgary’s Irish leaders had gotten ‘cold feet,’ he/she was implying that they lacked the courage to publicly celebrate their ethnic heritage. Further, ‘God Save Ireland’ was an explicitly nationalist slogan, associated with the last words of three Irish revolutionaries executed by the British in 1867. In short, Fitzsimmons was calling for an open celebration of Irish identity that did not shy away from nationalist politics. What Fitzsimmons saw as a simple issue, however, was much more complex for the majority of Irish people in Calgary and across Alberta. The often turbulent politics of the Irish homeland, and the campaign for Irish autonomy from Britain, raised difficult questions about what it meant to be Irish in Canada in the early twentieth century. Did public expressions of Irish identity automatically imply support for Irish nationalist politics, or could the two issues be separated? Could a person support Irish nationalism and still affirm loyalty to Canada and, by extension, the British Empire? What was the best way to frame St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in such a way as to affirm devotion to both the Irish homeland and Canada? The stakes of these questions were heightened after 1914, as supporters of Irish nationalism were accused of threatening British imperial unity during a time of war, and again after Easter 1916, when Irish nationalists launched an uprising against British rule in Ireland.

The uneasy relationship between Irish politics, identity and citizenship are reflected in the history of St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in early twentieth century Alberta. The general picture that emerges is of an Irish population that celebrated its ethnic heritage in ways that emphasized loyalty to Ireland, Canada and the British Empire. At particular times, such as the Great War (1914-18), this balancing act proved to be too difficult, and St. Patrick’s Day celebrations largely disappeared from public view. With the emergence of Ireland as an independent state in the early 1920s, Alberta’s Irish once again organized into associations dedicated to celebrating Irish heritage and St .Patrick’s Day soon emerged as an important event in the province.

The population boom of the early 1900s set the stage for significant St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in both Edmonton and Calgary. The 1916 census enumerated 58,068 Irish people in Alberta, of whom approximately 63% were Canadian-born descendants of Irish immigrants; 25% were American-born descendants of Irish immigrants; and 12% were direct immigrants from Ireland (most of whom had arrived in Canada between 1905 and 1914). The diverse origins of the province’s Irish population were reflected in the decorations chosen for the 1908 St. Patrick’s Day banquet at St. Mary’s Hall in Calgary – the platform was decorated with Union Jacks and American flags, over which hung a silk banner with the phrase “Erin go Bragh” (‘Ireland forever’). Toasts were delivered to ‘The King,’ ‘Canada,’ ‘Alberta,’ ‘The United States’ and ‘Ireland’s Future,’ and the event closed with a rousing rendition of “God Save the King,” leaving little doubt that the guests’ vision of ‘Ireland’s Future’ involved its continued association with the British Empire.

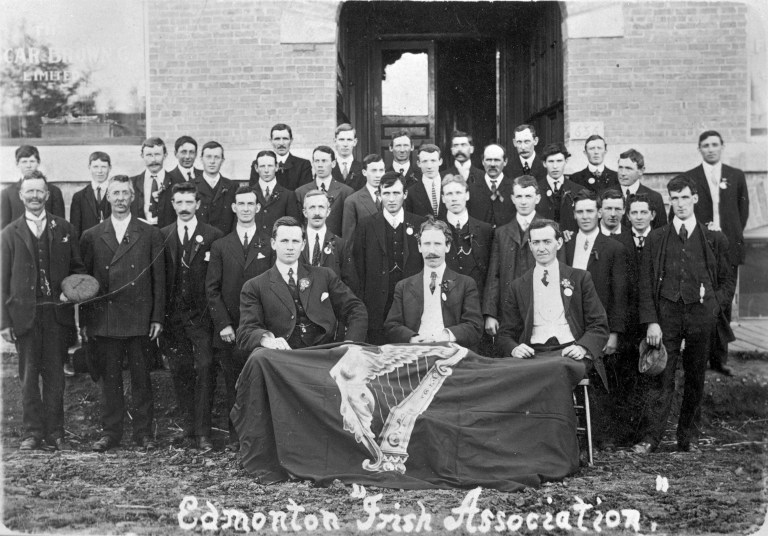

Similar scenes played out in Edmonton, where St. Patrick’s Day events were organized by the highly successful Edmonton Irish Association (EIA). Founded in 1909, the EIA grew to approximately three hundred members by 1911. While primarily a cultural and literary organization, the EIA also sponsored a number of sports teams, including the Irish Canadian Amateur Athletic Association, the Hibernian Football Club and the Irish Canadian Baseball Club. A 1911 profile in the Edmonton Capital stressed that the EIA was “non-political and non-sectarian in character,” and had “from the outset avoided the controversial.” This emphasis echoed the celebrations in Calgary, and indeed reflected a broader pattern across the Prairie West, where explicitly non-political and non-sectarian Irish associations emerged in the early 1900s.

With the worsening Home Rule crisis in Ireland in 1913-1914, it became increasingly difficult for Alberta’s Irish to continue to celebrate their ethnic heritage in an explicitly non-political way. In April 1914, for example, the Edmonton Capital advertised a meeting for those interested in forming an “Imperial British-Irish Association,” suggesting that some of the city’s Irish were no longer satisfied with the Edmonton Irish Association. The outbreak of World War One added another layer of complexity, as the British government put Ireland’s political future on hold for the duration of the war. By the end of 1914, the Edmonton Irish Association had dissolved. Similarly, there is no evidence of any Irish fraternal or benevolent societies in Calgary during the war years. Despite the non-political and non-sectarian nature of pre-war St. Patrick’s Day events, there appears to have been little appetite for Irish organization and celebration during the Great War or the subsequent Irish War of Independence (1919-21). The one exception is a short lived organization called the Irish Glee Club, which emerged in Calgary in 1919 to organize small concerts on St. Patrick’s Day. These events, however, were on a considerably smaller scale than those held prior to World War One.

With the end of the Irish War of Independence and the emergence of the Irish Free State in 1922, the province’s Irish citizens once again organized to publicly celebrate Ireland’s patron saint. Potentially awkward questions about how to reconcile devotion to Ireland and loyalty to Canada and/or Britain faded, as Alberta’s Irish honoured both Irish independence and service to Canada during the Great War. At the 1924 St. Patrick’s Day banquet, for example, the St. Patrick’s Society of Calgary celebrated Irish independence, but placed equal if not greater emphasis on Irish service, “loyalty and allegiance” to Canada during the Great War. The evening’s keynote speaker refused to take a political stance on the divisive civil war in Ireland, commenting only that “the Irish had settled the matter for themselves,” and that whether it had been settled “rightly or wrongly” was irrelevant to him as a Canadian. In place of politics, the new St. Patrick’s Society focused on the celebration of Irish folk culture, arts and crafts. A similar situation emerged in Edmonton, with the founding of the new St. Patrick’s Society of Edmonton in 1927. Like its Calgary counterpart, the society emphasized culture and avoided politics – a safely depoliticized way to honour Ireland. By the mid-1920s, Alberta’s Irish had found a comfortable balance between celebrating their Irish heritage and their contributions to Canadian growth and development.

The history of St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in Alberta thus yields significant insight into the province’s early Irish community. St. Patrick’s Day events represented an important point of intersection between the ethnic community and the rest of the population. It was a holiday intimately associated with Ireland, but widely observed by mainstream society – as such, it offered Irish organizations the opportunity to represent their heritage and their community’s values to a wide and receptive audience. The nature of those celebrations (or the absence of any organized events) is a reflection of what image Irish community leaders wanted to project to the larger population. At times, the tense situation in Ireland complicated those efforts and made it difficult for Alberta’s Irish to publicly embrace and celebrate their ethnic heritage. By the 1920s, such concerns had faded and St. Patrick’s Day celebrations flourished once again.

Written by: Allan Rowe, Historic Places Research Officer.

Further reading:

Cronin, Mike, and Daryl Adair. The Wearing of the Green: A History of St. Patrick’s Day. London & New York: Routledge, 2001.