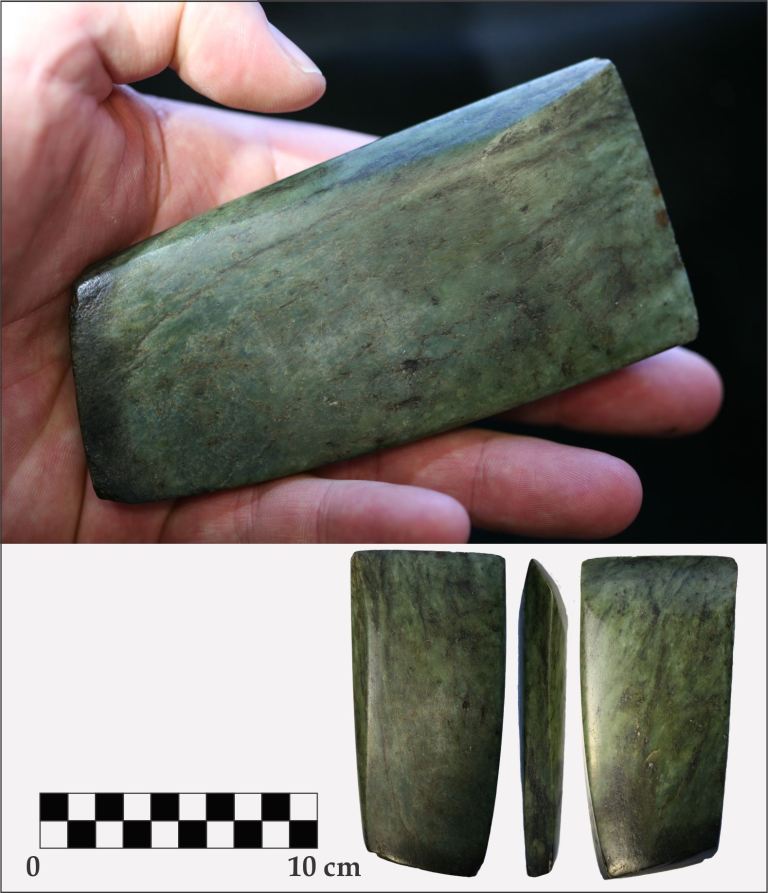

With no jade mines or known quarries in the province, you may be surprised to learn that people used jade in Alberta thousands of years ago. Jade is a common name that refers to two minerals, one of which, nephrite, is found in Canada.

Nephrite is one of the toughest natural materials on earth and for this reason, ancient people used it to make tools called celts. Tightly interlocking bundles of amphibole crystals (actinolite/tremolite) make nephrite incredibly resistant to fracture so the celts retain their sharp edges despite hours of wood-working with them.

How did people make jade or nephrite celts? Slowly! As in modern times, nephrite was too strong to chip with a chisel so it was patiently sawed and ground with materials like sandstone and quartz crystals and polished with a slurry of gritty water. Jade occurs in outcrops across British Columbia where some First Nations had specialized jade workers. Most of the evidence for Aboriginal nephrite working comes from the Fraser River of southern B.C. near Lytton, Lillooet, and Hope. While the celts manufactured by pre-contact people were certainly functional, the rarity of jade and the time it took to make celts would have resulted in a highly revered and prized type of tool.

Nephrite celts have been recovered from several farmers’ fields across Alberta but have never been found during an archaeological excavation in the province. They are generally more common in northern Alberta where First Nations likely maintained stronger trading connections to people from B.C. than in the south.

Based on historic records and tools used by First Nations shortly after European contact, jade celts were most likely tied onto wood or antler handles to increase the force that people could apply to the tool. The Alberta celts are thought to have been either ceremonial, status-markers, and/or they were used to build boats or prepare wooden poles.

Written By: Todd Kristensen (Regional Archaeologist, Archaeological Survey), Jesse Morin (Heritage Consultant), and Karen Giering (Curatorial Assistant, Royal Alberta Museum)

Acknowledgements

Staff from the Archaeological Survey, Royal Alberta Museum, and University of Alberta collaborated with museums and farmers across Alberta to analyse our rare jade artifacts. Jade expert Jesse Morin from B.C. analysed specimens and lent his knowledge to the project. Full results, including geochemistry, mineralogy, and archaeological significance of Alberta’s jade will appear in an Occasional Paper Series article that will be available to the public shortly. Thanks to all the researchers for their help and thanks to the museums and farmers for kindly loaning artifacts for this study!