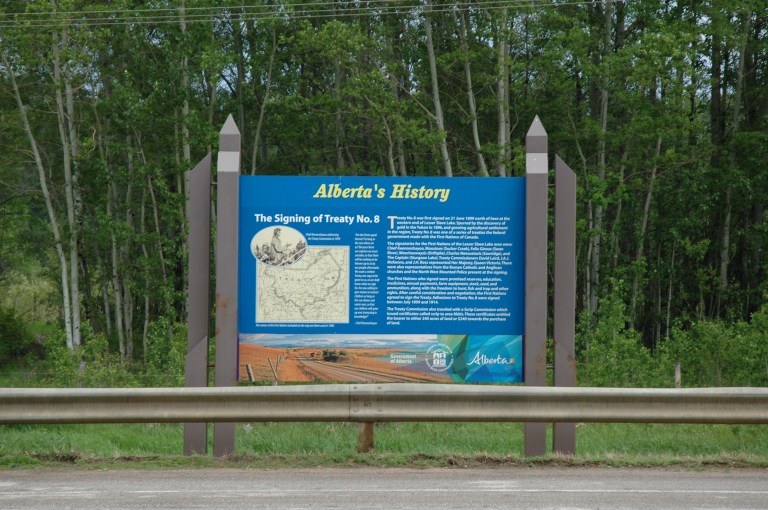

You have all probably seen them – large blue heritage markers located at highway rest areas or points of interest throughout Alberta. These interpretive signs tell of Alberta’s rich heritage. Come, travel Alberta and read a featured heritage marker:

Driving westward on Highway 18, I found this roadside sign a few kilometers east of the Highway 33 intersection, near the Town of Barrhead. Stopping to read it, I learned how close I was to the “all Canadian” route to the Klondike, used during the gold rush. Continuing on my way, I used part of the trail (now Highway 33) to get to High Prairie.

Driving westward on Highway 18, I found this roadside sign a few kilometers east of the Highway 33 intersection, near the Town of Barrhead. Stopping to read it, I learned how close I was to the “all Canadian” route to the Klondike, used during the gold rush. Continuing on my way, I used part of the trail (now Highway 33) to get to High Prairie.

Klondike Trail

When gold was discovered on the Klondike River in 1896, a frenzy swept North America. By 1897 a full-scale gold rush was on. Most “Klondikers” traveled by ship to Skagway in Alaska before crossing the White and Chilikoot Passes to the Yukon. Some, however, chose alternative routes. The Canadian government, the Edmonton Board of Trade, and Edmonton merchants promoted use of an “all Canadian” route. Gold seekers were encouraged to travel from Edmonton to the Yukon via the Peace River Country. Existing trails were very rudimentary, so the government hired T.W. Chalmers to build a new road between Fort Assiniboine and Lesser Slave Lake.

After an initial survey in September 1897, construction of the road was started in the spring of 1898. The Chalmers or Klondike Trail began on the Athabasca River at Pruden’s Crossing, near Fort Assiniboine. Located to the east of this sign, the trail skirted the present site of Swan Hills before following the Swan River north to what would become Kinuso. From there, travelers followed the shore of Lesser Slave Lake west before turning north to the goldfields – a mere 2,500 kilometers away.

The trail followed a very difficult route and was a challenge to all. Countless numbers of horses perished along the way, and travelers’ accounts describe the back-breaking labour and dangers of this trail. By 1901-02 use of the trail declined, and soon after it was abandoned altogether in favour of other routes to the Peace River area. Highway 33, just east of here, roughly follows the route of this early trail, which is linked to one of the most colourful episodes in Canadian History.

Heritage Marker Location

North side of Highway 18, 1 kilometer east of Highway 33.

Prepared by: Michael Thome, Municipal Heritage Services Officer