Written by: Allan Rowe (MA, PhD), Heritage Marker Program Coordinator

More digital content about Euphemia McNaught: McNaught Homestead Preservation Society, McNaught Homestead Provincial Historic Resource, Art Gallery of Grande Prairie, Alberta Foundation for the Arts, Provincial Art Collections.

In his introduction to the book Euphemia McNaught: Pioneer Artist of the Peace, Robert Guest described Euphemia McNaught as “a chronicler of the Peace River Country and the pioneer era” (Guest 1982, p.22). McNaught’s art reflected a deeply felt connection to place that was born out of her family’s experience homesteading in the Beaverlodge area in the early 1910s. In addition to illustrating the striking natural beauty of the region’s landscape, her paintings captured the advance of agricultural settlement in the Peace River Country, a process that fundamentally transformed the region in the early- to mid-twentieth century.

Agricultural settlement advanced gradually across western Canada from the 1870s to the early 1900s, with hundreds of thousands of settlers from eastern Canada, the United States and Europe claiming land through purchase or homesteading. The Government of Canada promoted western Canada as “The Last Best West,” a region bursting with agricultural potential and economic opportunity. The catchy slogan promoted the idea that the Canadian Prairie West was, by the early 1900s, the last region in North America where homestead land was widely available. Government posters showed scenes of bountiful harvests and contented families with “homes for millions” still available. The population of the Canadian Prairie West soared in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, climbing from almost 420,000 in 1901 to nearly two million by 1921, approximately 590,000 of whom lived in Alberta.

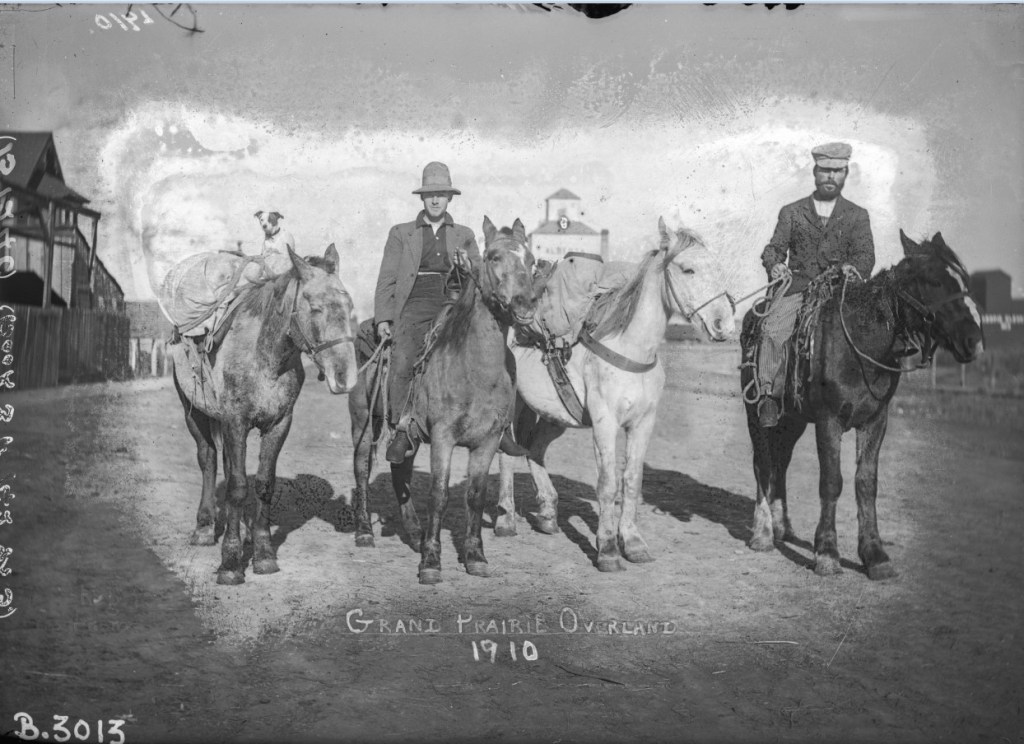

When the McNaught family arrived in the Beaverlodge area in 1910, however, they were part of the first major wave of homesteaders to take up land in the region. While agricultural settlement had exploded in southern and central Alberta in the early 1900s, it was very slow to arrive in the Peace River Country – it was the last significant part of the “Last Best West” to get a major surge of agricultural settlers. Despite its many natural advantages, the Peace River Country faced a number of challenges that significantly delayed agricultural settlement.

The first key reason was the region’s isolation from major transportation routes – for example, while major railway lines had reached Calgary in 1884 and Edmonton in 1891, there was no railway connection to the Peace River Country until the early 1910s. This lack of transportation infrastructure isolated the region from major markets, making it less attractive to settlers (Wetherell and Kmet 2000). Second, there was sharp and at times heated disagreement over the suitability of the region’s soil and climate for large-scale agriculture. The Geological Survey of Canada’s assessment in the 1870s was generally positive but more critical voices were raised over the next several decades. The most damning assessment came from botanist James Macoun, who concluded in 1903 that the upper Peace River Country “will never be a country in which wheat can be grown successfully” and that the region was “emphatically a poor man’s country” (Macoun 1974, pp. 212-13). Macoun noted that earlier positive assessments had been focused on the river valley rather than the region as a whole and argued that early frosts would make large-scale commercial agriculture impossible (Wetherell and Kmet 2000, p. 83). This assessment was quickly challenged by regional boosters but overall opinion about the region’s agricultural potential was at best mixed by the 1900s. As a result, the Government of Canada did little to specifically promote the Peace River Country as a destination for immigrants seeking land.

The Government of Canada’s general lack of interest in the region’s was also reflected in its failure to negotiate a treaty with First Nations leaders until 1899. The Government of Canada had taken this step in much of present-day Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta by negotiating the Numbered Treaties in the 1870s. The spirit, intent and consequences of these treaties remain issues of significant controversy to this day; however, in the late nineteenth century, these treaties were viewed by the Government of Canada as the legal means by which Aboriginal title over land was surrendered in return for reserve land, annual payments and other rights, such as hunting and fishing over unoccupied crown land (Filice 2016). With little pressure for agricultural settlement or other economic development, the Government of Canada felt no urgency to address Aboriginal title.

The situation changed dramatically with the start of the Klondike Gold Rush in 1896, which triggered a significant influx of prospectors into the Peace River Country. While these prospectors were travelling through rather than settling in the region, the sudden presence of hundreds of prospectors (many from the United States) compelled the Government of Canada to establish a stronger presence in the Peace River Country. The North-West Mounted Police were dispatched to establish Canadian authority and maintain order. New proposals for railways into the Peace River Country were quickly proposed, which in turn raised the prospect of greater long-term settlement. These factors finally pushed the Government of Canada to address Aboriginal title. In 1899, federal treaty commissioners, with the assistance and support of the North-West Mounted Police and the Catholic and Anglican Churches, began negotiations with the Cree, Denesuline (Chipewyan) and Dane-zaa (Beaver) First Nations. Treaty 8 was signed in 1899 and covered 840,000 square kilometres in present-day Alberta, Saskatchewan, British Columbia and the Northwest Territories. Adhesions to Treaty 8 were later negotiated with First Nations who had not been present at the original negotiation in 1899 (Tesar 2016). The government also launched a Scrip Commission to address Metis land claims in the region. From the perspective of the Government of Canada, these various measures had extinguished Aboriginal title in the Peace River Country, laying the foundation for further economic development.

The signing of Treaty 8 did not immediately trigger a major influx of agricultural settlers – there was still debate over the region’s farming potential and no railways were built by the turn of the twentieth century. However, a variety of factors created momentum for agricultural settlement in the coming years. First, Alberta was established as a province in 1905 and the new provincial government strongly promoted settlement in the Peace River Country (Wetherell and Kmet 2000, p. 88). Second, the federal government took a more active role promoting the Peace River Country after Frank Oliver was appointed Minister of the Interior in 1905. Oliver was a Member of Parliament from Edmonton, editor of the Edmonton Bulletin and strong supporter of agricultural settlement in the Peace River Country. He promoted the region through his newspaper and through his government office, dismissing negative reports about the region’s agricultural potential (Irwin 1995, pp. 54-57). Promotion by regional boosters and the provincial and federal governments thus helped raise the profile of the Peace River Country as a suitable field for agricultural settlement.

On a more practical note, teams from the Dominion Lands Survey were sent to bring the Peace River Country into the same grid system that was in place for the rest of western Canada. Historian David Leonard describes the survey work as a “Herculean undertaking” as surveyors had to travel with heavy equipment over unforgiving terrain and heavy bush (Leonard 2005, p. 79). By 1912, a significant portion of the region’s arable land had been surveyed into quarter-sections and made ready for homestead claims. Most critically, the Edmonton, Dunvegan and British Columbia Railway was chartered in 1907, raising confidence that a railway to the region would finally be built. Construction on the railway that linked the Peace River Country to Edmonton finally began in 1912, thus securing the access to markets that was essential to making large-scale agricultural settlement viable.

When the McNaught family arrived in the Beaverlodge area in 1910, they were part of the first significant land rush into the Peace River region. They were among the fifty-nine newcomers who claimed land in the Beaverlodge area by the end of 1910, roughly half of whom (like the McNaught family) had come from Ontario (Leonard 2005, p. 181). Agricultural settlement continued at a steady pace through the 1910s and into the 1920s, described by historian Robert Irwin as a “continuous, on-going and permanent feature characterised by important waves of activity” rather than a “single, brief intensive burst of activity” (Irwin 1995, pp. 64-65). Euphemia McNaught arrived in the Peace River Country in the earliest stages of agricultural settlement and her drawings and paintings of cabins, homesteads and farmyards offer a unique window into the process that fundamentally transformed the Peace River region.

Sources:

Filice, Michelle. “Numbered Treaties.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published August 02, 2016; Last Edited August 02, 2016.

Guest, Robert. “Introduction.” In Euphemia McNaught: Pioneer Artist of the Peace. Edited by Isabel Perry. Beaverlodge & District Historical Association, 1982: 21-24.

Irwin, Robert Scott. “The Emergence of Regional Identity: The Peace River Country, 1910-46.” PhD diss. University of Alberta, 1995.

Leonard, David. The Last Great West: The Agricultural Settlement of the Peace River Country to 1914. Calgary: Detselig, 2005.

Macoun, James M. “1903: An Adverse Report.” In Peace River Chronicles, edited by Gordon E. Bowes. Vancouver: Prescott Publishing Company, 1974: 212-13.

Tesar, Alex. “Treaty 8.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published August 29, 2016; Last Edited August 29, 2016.

Wetherell, Donald G. and Irene R.A. Kmet. Alberta’s North: A History, Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2000.