Editor’s note: September 30 is National Day for Truth and Reconciliation and Orange Shirt Day. Reading residential school histories can be a painful process. If reading this is causing pain or bringing back distressing memories, please call the Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419. The Crisis Line is available 24 hours a day and can also provide information on other health supports provided by the Health Canada Indian Residential Schools Resolution Health Support Program.

Written by: Laura Golebiowski (Indigenous Consultation Adviser) in collaboration with Whitefish Lake First Nation #128.

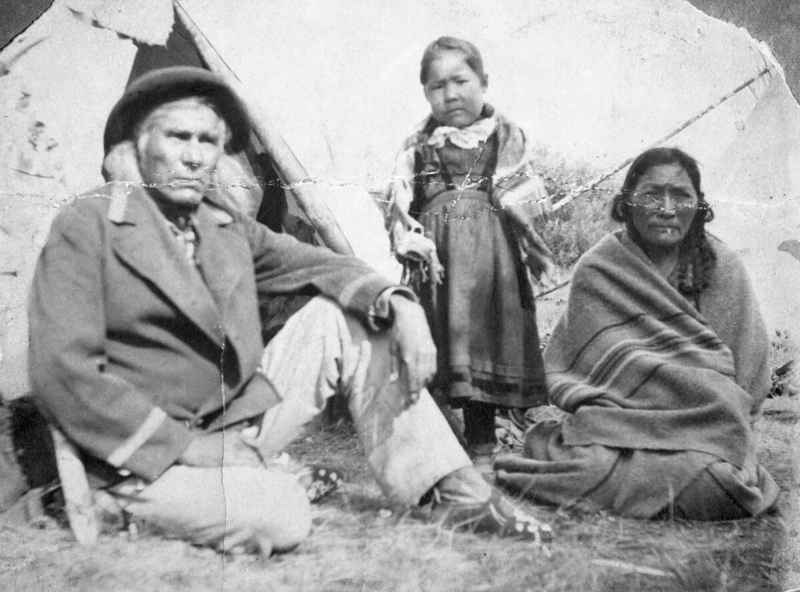

Emma Stanley was born in 1886, in the area known today as Whitefish Lake in northeastern Alberta. Her mother was Eliza and her father was Cheepo-Koot, or Charles. She had at least two sisters. The last name Stanley was assigned to Indigenous families upon christening by the Methodist ministers of time. These assigned names are still known and common in the community today.

Emma and her family were members of James Seenum’s Band, contemporarily known as Whitefish Lake First Nation #128. Their leader was Chief Pakan, or James Seenum: “a very forceful and highly respected figure.” When the Nation signed Treaty Six, Cheepo-Koot was selected as one of three Councillors.

In the years and decades prior to Emma’s birth, James Seenum’s Band members lived by the Cree seasonal round, which influenced their hunting, fishing, agricultural and travel practices. “In the spring-time, after the potatoes and turnips were planted, [the people] went south on their buffalo hunt, leaving the missionary and a few of the older people at home to look after the place and anything that had to be done. They would travel till they came to the buffalo range. After a good day’s hunt there was lots to do, such as curing the meat so it would keep. The surprising thing was that there was no such thing as flies to bother the fresh meat.”

Hunting, fishing and trapping was supplemented by the agricultural practices introduced by Shawahnekizhek, or Reverend Henry Bird Steinhauer—an Ojibway man who traveled west to establish the first Methodist missionary Whitefish Lake. As Sam Bull (himself a Survivor of Red Deer Industrial School) recalled in 100 years at Whitefish 1855-1955: “The weather was so favourable for the growth of crops that we never witnessed crop failures. There was a good steady rainfall which lasted four days, starting in June. For a livelihood there was plenty of fishing from the lakes and hunting of wild life galore.”

Emma, however, was born in the months immediately following the Northwest Resistance. James Seenum’s Band returned to Whitefish Lake from the west, where they had retreated to the bush in the wake of the conflict at Frog Lake. Their log homes had been ransacked and bullets remained lodged in the walls. The community worked hard to rebuild. “As the people had fled the previous spring, nobody had taken time to put in their crops. There was no grain or potatoes, just a few stacks of grain left from the preceding autumn but these were spoiled owing to heavy rains.” Rations were provided to family members.

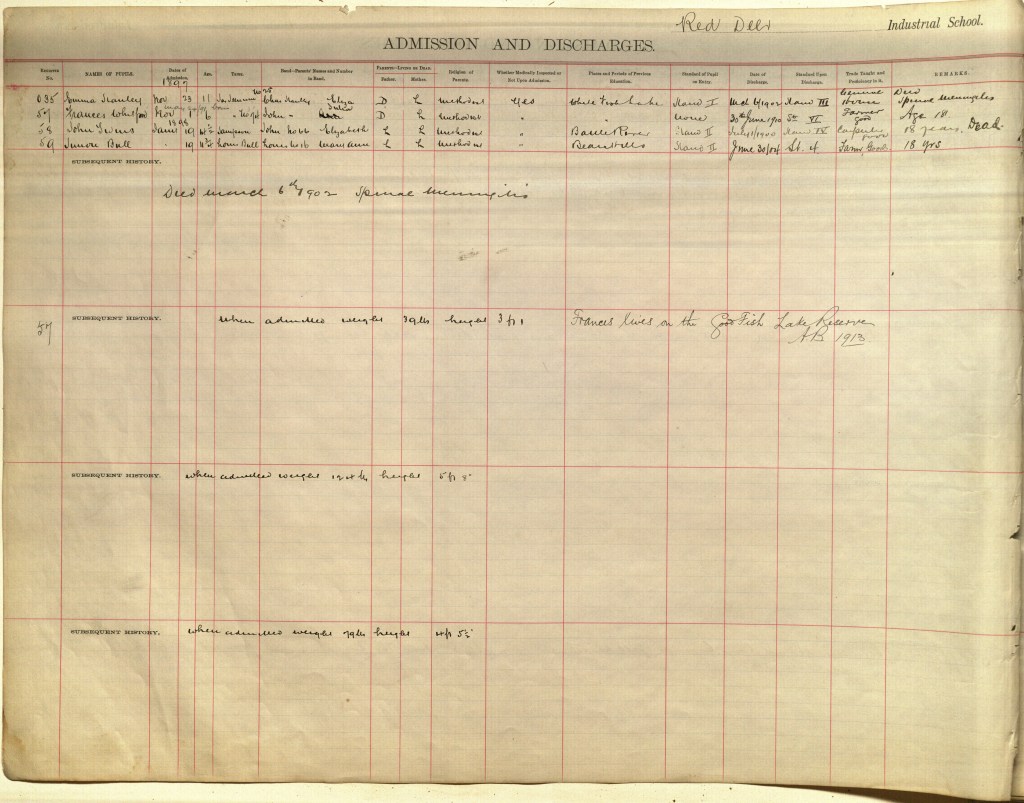

On November 23, 1897, Emma Stanley was admitted to Red Deer Industrial School. Cheepo-Koot had passed away, and the family had moved in with Emma’s sister and brother-in-law, Jacob Bull. Though she had received some previous education at Whitefish Lake, we can imagine Emma’s confusion and loneliness upon entering an institution located more than 300 kilometres south of her home and family. Like all children forced to attend industrial school, Emma spent half her day in the classroom and the other half working in an assigned trade; Emma’s was “general house[keeping].” She was 11 years old.

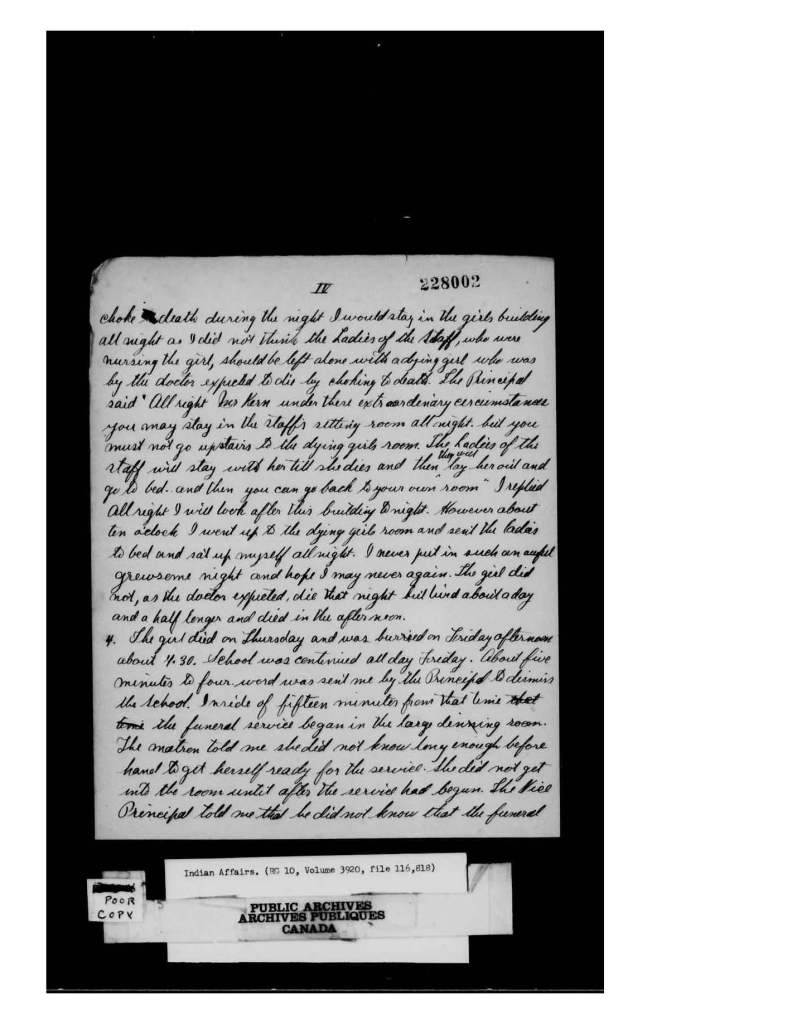

In the winter of 1902, Emma grew very ill. At the time, her condition was referred to as either spinal meningitis or “tuberculosis of the brain”—inarguably caused and exacerbated by the poor sanitation and ventilation systems that plagued Red Deer and numerous other industrial and residential schools. Daniel S. Kearn, an instructor who accompanied Emma for a portion of the night before she died, wrote: “I never put in such an awful gruesome night as hope I never may again.”

Emma died on a Thursday afternoon on March 6, 1902. The exact circumstances surrounding Emma’s death are contested within the archival record; claims made by Mr. Kearn were later denied by the school principal. We know she died far away from her family and the cultural traditions and practices she belonged to. She was 16 years old.

Emma was buried in the Red Deer Industrial School cemetery the next day. According to Mr. Kearn, her funeral was a rushed affair. “The matron told me she did not know long enough beforehand to get herself ready for the service. She did not get into the room until after the service had begun. The Vice Principal told me that he did not know that the funeral service was taking place till he saw the corpse carried out to the sleigh. The children were attired in their working clothes or school clothes. The coffin used was a plain, stained board coffin, apparently made by the carpenter instructor.”

In subsequent letters, the school principal refuted this too, stating: “Her funeral was conducted in the most becoming manner in every respect.”

Emma Stanley is one of at least 70 children who died as a result of their forced attendance at Red Deer Industrial School. The above narrative has been compiled using archival sources; however, we know the greatest sources of truth when telling residential school histories come from Indigenous community testimony and family recollection. The Historic Resources Management Branch is honoured to be collaborating with twelve Survivor communities regarding the preservation and recognition of the Red Deer Industrial School cemetery.

Thank you to Whitefish Lake First Nation #128 for helping us tell the story of Emma Stanley and Red Deer Industrial School. Special thank you to Councillor Louise Hunter and Darryl Steinhauer. Hiy hiy.

References:

Bull, Sam. 100 years at Whitefish 1855 – 1955. United Church Congregation. Retrieved online from: https://glenbow.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/m-203-28.pdf

Dominion of Canada. (1897). Sessional papers of the Dominion of Canada: volume 11, second session of the eighth Parliament, session 1897:1897. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved online from: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_08052_31_11/2

General correspondence relating to the Red Deer Industrial School from its inception, 1889-1912. RG10, Volume number: 3920, Microfilm reel number: C-10161, File number: 116818. Library and Archives Canada.

National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. National Student Memorial for Red Deer Industrial School. Retrieved online from: https://nctr.ca/residential-schools/alberta/red-deer-industrial-school/

Red Deer Industrial Student Register, Provincial Archives of Alberta PR1979.0268/162.

Steinhauer, Melvin D. (2015). Shawahnekizhek: Henry Bird Steinhauer: Child of Two Cultures. Edmonton: Self-published.