Editor’s note: Tansi! June is National Indigenous History Month, the opportunity to learn about the unique cultures, traditions and experiences of Indigenous communities in what is now Alberta and across Canada. This month also marks the 125th anniversary of the signing of Treaty 8, which encompasses a land mass of approximately 840,000 kilometres and includes portions of Alberta, British Columbia, Saskatchewan and the Northwest Territories. In Alberta, much of Treaty 8 territory is delineated by the Athabasca River extending north. Treaty 8 territory also includes the north shore of Lac La Biche extending northeast to the Saskatchewan border, as well as portions of Jasper National Park.

The banner image above is courtesy of Laura Golebiowski.

Written by: Laura Golebiowski (Indigenous Consultation Adviser) in collaboration with Woodland Cree First Nation.

“I believe Spring speaks its truest word when you can see the women setting out pails to get that sap from the birch tree,” Chief Dan George narrates in the 1973 film Season of the Birch. The short documentary focuses on intangible heritage knowledge and practices that are still present in Cree communities in Treaty 8 today: the tapping of birch trees and the making of birch syrup.

The window for birch tapping is incredibly narrow. The waskwayâpoy (birch sap) runs best in the early spring when the snow has melted, but before the tree leaves appear. At the kind invitation of Lawrence Lamouche, Traditional Lands Manager, I visited Woodland Cree First Nation in late April, to witness this centuries-old practice and learn how Knowledge-Keepers harvest waskwayâpoy and make birch syrup.

Woodland Cree First Nation, whose territory includes the Peace River region and is comprised of the reserve communities of Cadotte Lake, Simon Lake, Golden Lake and Marten Lake, signed an adhesion to Treaty 8 in 1991. 125 years ago, when Treaty 8 was first negotiated and signed among the Cree, Dene and Beaver Peoples who occupied what is now Alberta, birch tapping was observed by Commission member Oliver Cromwell Edwards. In his journal, he wrote of the Lesser Slave Lake area:

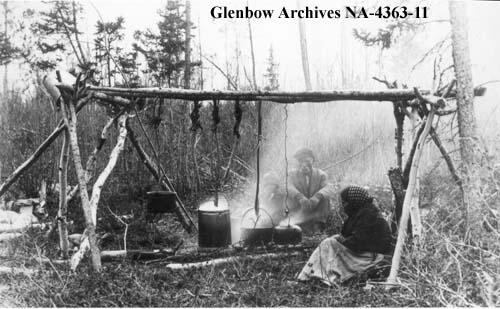

… I noticed several camping places that puzzled me—two uprights and a strong crossbar of wood from which were hanging a dozen or more pot hooks of wood blackened by smoke. I thought the Indians had been in some way curing fish but on enquiring at the Lake village I found that these were camping places used by the Indians in making a syrup from the birch tree—I was not aware before that the sap of the birch was treated in a manner similar to the maple.

On this afternoon, Lawrence and I meet Knowledge-Keeper Nancy Williams, who has already begun tapping several trees along a small lake. This area, northeast of Cadotte Lake, has been accessed by the matriarchs of Cree families, including the Cardinal and Laboucan families, for generations. Nancy’s kôkum harvested in this area, and today she and her daughters continue to tap here.

Nancy and her family use traditional methods to harvest the majority of the waskwayâpoy. A knife is used to cut a V-shape through the exterior, paper layers of the birch bark. Care is taken to not damage the internal cambium layers unnecessarily. A slender willow branch is stripped of its bark and a slit is cut on one end to attach to the V-shape, forming a lip and channel to direct the birch water into the bucket below. An axe is used to cut a small notch above the lip. In the spring when the sap is running, the cut instantly begins leaking birch water. Nancy kneels at the one tree that’s been the unfortunate victim of my first attempt (read: hack job), carving out a cleaner notch with her knife. She runs her finger from the cut down the truck, guiding the waskwayâpoy to the willow branch.

Nancy and Lawrence walk the forest with intention, looking for the best birch to tap. The trees that produce the most waskwayâpoy are often located in sunny spots; the sap runs faster during the day and slows significantly in the evening and overnight.

As we walk south along the lakeshore, we spot trees bearing healed scars of past harvests. Lawrence can even identify his signature ‘fox-face’ cuts from three years ago. In accordance with the land stewardship practices they have always known, Woodland Cree First Nation members do not return to the same tree year after year. Instead, once tapped, a birch is left to rest and heal for at least the next three seasons. Through Lawrence’s relationships with forestry operators in the region, he has obtained spatial data of existing birch stands within Woodland Cree First Nation’s territory. These areas will be considered for future waskwayâpoy harvests, as more community members continue the practice.

The next day, most of the buckets are at least half-full of waskwayâpoy. My poor tree hasn’t produced much water, and is also the only bucket filled with drowned bugs. I try to tell Nancy it’s because I’ve chosen the sweetest tree—I’m not sure she believes me. Woodland Cree First Nation members also drink the tapped waskwayâpoy as-is: it is hydrating and the natural sugars mean that some people liken it to “nature’s Gatorade.” Nancy and her daughter Sara gather the water into larger, plastic pails.

A propane stove and large pots are set up outside the band office. The waskwayâpoy is strained and set over low heat; too aggressive of a boil will cause all the water to evaporate. Unlike maple sap (with a ratio of approximately 40:1), birch sap contains considerably less sugar (approximately 120:1), meaning that more birch water is required to produce syrup.

It’s a time-consuming, monotonous labour of love, but spirits are high and the company is good. Elders, Leadership and community members visit throughout the day, asking questions or sharing their own experiences birch tapping. In the late afternoon on Tuesday, a van brings the Nation’s youth to the lake. For several, this is their first exposure to the practice. Lawrence reflected: “It was awesome to hear stories of how Elders used to see their parents or kôkums harvest syrup and to see the kids learn and try for the first time, it was priceless.”

In the days that follow, dozens of jars of both waskwayâpoy and syrup are canned and distributed to community members. The syrup is used as sweetener, in coffee or with bannock. The sweetest reward, however, is the opportunity for the community to come together, to be out on the land, and to transfer this knowledge to the younger generation. Lawrence says: “It’s very important that we keep learning and teaching each other to preserve our culture and traditional practices together.”

Thank you to Lawrence Lamouche and Woodland Cree First Nation for the invitation, and to Nancy Williams, Sara Williams, Amethyst Williams and Lawrence for sharing their knowledge and experiences. Ekosi.

References and further learning:

Gregoret, Gene. (1973). “Season of the birch.” YouTube, uploaded by Gene Roy, 19 April 2021. Retrieved online from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pbWzztB08Mk.

Leonard, David and Beverly Whalen (eds.). (1999). On the north trail: The Treaty 8 diary of O.C. Edwards. Published by the Alberta Resources Publication Board, Historical Society of Alberta. Altona, MB: Friesens Corporation.

Woodland Cree First Nation. (2015). “Woodland Cree First Nation – A vision for the future.” YouTube, uploaded by NSCA Video Channel, 4 December 2015. Retrieved online from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2IVQgNi5cOE.

Woodland Cree First Nation. (2015). Welcome to Woodland Cree First Nation. Retrieved online from https://www.woodlandcree.net/.

“Season of the birch” is a reference to the Gene Gregoret 1973 film of the same name. Banner image is courtesy of Laura Golebiowski.