Editor’s note: September 30 is National Day for Truth and Reconciliation and Orange Shirt Day. Reading residential school histories can be a painful process. If reading this is causing pain or bringing back distressing memories, please call the Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419. The Crisis Line is available 24 hours a day and can also provide information on other health supports provided by the Health Canada Indian Residential Schools Resolution Health Support Program.

An earlier version of this article appeared in the December/January 2024 issue of Nisichawayasi Achimowina.

Written by: Laura Golebiowski (Indigenous Consultation Adviser), in collaboration with Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation.

“Eight children, an equal number of boys and girls, were going with us to enter a Residential School… I applied, but without success, to the Principal of the Brandon Residential School, for the admittance of the Indian children. That they were “non-treaty” was the alleged objection. As, however, the Red Deer school was willing to receive them, we decided to take them there…In the course of two or three years, five of those apparently healthy children had died from Tuberculosis.”

– Samuel Gaudin, in Forty-Four Years with the Northern Crees

Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation are the Nisichawayasi Nehethowuk: the people whose ancestors lived near where the three rivers meet and who speak Nehetho, the language of the four winds. Their territory includes the rich lands of the Canadian Shield and boreal forest in what is now northern Manitoba. Their central community hub is located at Nelson House, a long-time place of Indigenous occupation where the Hudson’s Bay Company established a trading post in the late 1700s.

This landscape of rocky shorelines and many rivers, streams and lakes is remarkably far from Red Deer, Alberta. And yet, in October of 1900, eight children from Nelson House were taken from their home and admitted to the Red Deer Industrial School. They travelled the rivers, streams and lakes in one birch bark and one Peterborough canoe, watching the landscape become increasingly unfamiliar. First denied entry to Brandon Industrial School on account of their non-Treaty status, the children were then taken to Red Deer by missionary Samuel Gaudin.

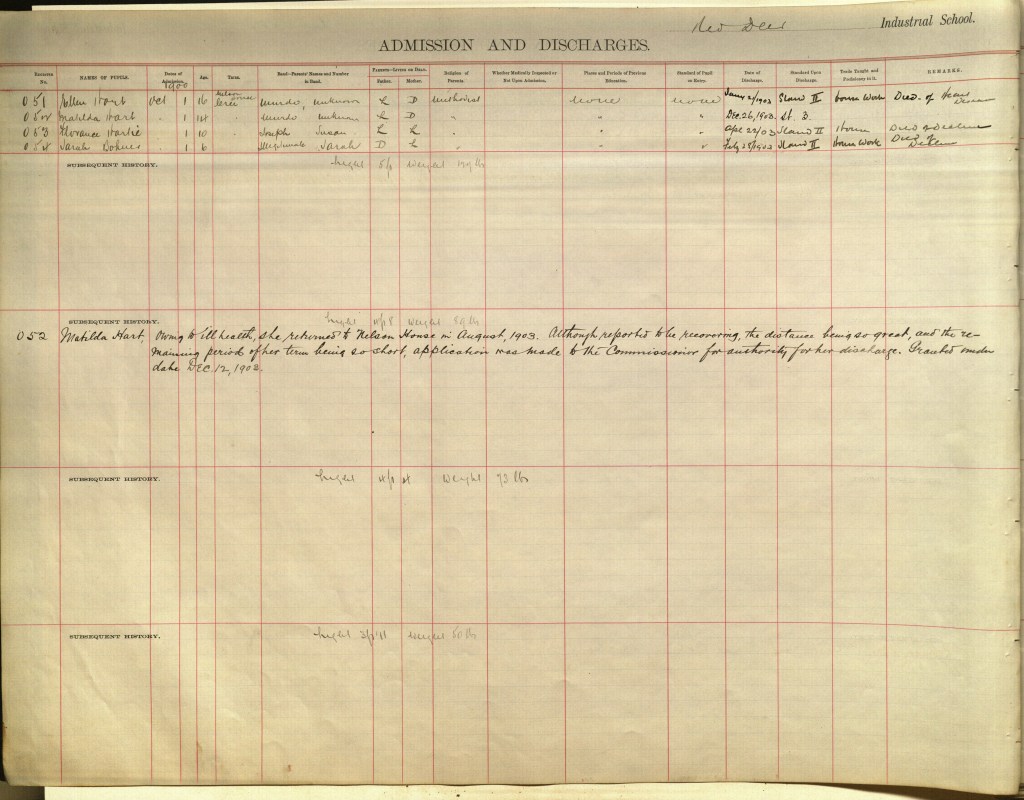

Their names were Isaac Bohner, Sarah Bohner, Ellen Hart, Matilda Hart, Florence Hartie (in the archival record, the last name Hartie also appears as Hardy), Richard Hartie, John Sinclair and Robinson Spence. More than a thousand kilometres separated these children from their families, community, and culture. They were so far from home.

In their 2016 history publication, Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation wrote:

The goal [of residential school] was to acculturate Aboriginal children into the European-dominated Canadian society by removing them from the cultural influences of their home communities. They were often forbidden to speak their native languages or observe their traditional beliefs. Families were split up and children from the same family were sent to different schools or were not allowed to share rooms with their siblings…The schools were underfunded, often poorly managed and badly built. Because of underfunding, students were rarely fed well and lived in overcrowded housing. Disease and death were common early in the past century and horrible health conditions were ignored. Children were called dirty savages and their self-esteem suffered.

By 1906, Sarah, Ellen, Florence and John had died. Their causes of death in the student register include “consumption” and “decline”—illnesses inarguably caused and exacerbated by the poor sanitation and ventilation systems that plagued Red Deer and numerous other industrial and residential schools.

Ellen Hart was sixteen years old when she was admitted to Red Deer. She was Matilda’s older sister; both girls were assigned “housework” as their vocational trade in the industrial school. On January 20, 1903, Ellen died at school of reported heart disease. Her grave marker, made of wood, is one of four that remain today, and is on display at the Red Deer Museum and Archives.

According to the archival record, Isaac, Richard, Matilda, and Robinson survived Red Deer Industrial School. Richard was “discharged at the strong request of his father,” presumably following the death of his sister, Florence. According to the book Anna and the Indians (a fictionalized retelling of her life and work in northern Manitoba), Anna Gaudin wrote an impassioned letter requesting that Matilda—the last surviving girl—return to Nelson House. Matilda was formally discharged from Red Deer on December 12, 1903. “How glad that girl was to be on her way home, away from what to her was a dismal school,” wrote Samuel Gaudin in his memoir Forty-Four Years with the Northern Crees.

Isaac and Robinson were both set to return home to Nelson House when—heartbreakingly—they missed their boat and instead were transferred to Brandon Industrial School. Though Robinson survived both Red Deer and Brandon, the devastating intergenerational legacy of residential schools is made very real through his son’s Clifford Spence’s testimony:

My name is Clifford D. Spence. I was born on October 26, 1945 in waskwatum – oskotimi sakahikanihk (Beaver Dam Lake).

I had two sisters and four brothers: Margaret, Mary Lou, Sandy, John, Simon, Jimmy and Roy. When I was young (a baby), I lived with seven different families because my dad Robinson Spence was a mailman for the northern area: Wabowden, Cormorant, Sherridon, Lynn Lake and South Indian Lake.

When they left, my mom Dinah would go with my dad; they would travel by dog team. They took turns running in front of the dog team, breaking trail.

They would leave Nelson House to Wabowden, then to Cormorant, Sherridon, Pukatawagan, Lynn Lake, then to South Indian Lake and back to Nelson House. It took them three months…when he returned to Nelson House, all the mail would be returned to Wabowden to be shipped out by train.

This is why I lived with seven different families. I never did go trapping, fishing or hunting with my dad.

The last time I saw my dad was in 1956 when he took me by the collar. He took me down to the lake and put me in a plane to go to school at Norway House. That was the last time I saw my dad.*

*Clifford Spence’s handwritten testimony has been transcribed and edited for clarity.

Red Deer Industrial School has been closed for more than a century, but the lives and stories of these eight children—those who survived and those who did not—are still known. In late August 2023, I had the great privilege of visiting Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation to discuss the Red Deer Industrial School cemetery preservation and recognition initiative. This visit was preceded by numerous discussions over phone and email and two prior visits from Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation Elders and Knowledge-Keepers to Alberta, to visit the cemetery, conduct ceremony and to meet representatives of the eleven other Nations that survived Red Deer Industrial School.

Over the course of several hours, the archival material relating to Red Deer was reviewed, corroborated, bolstered, and sometimes contested by Nisichawayasihk community knowledge and family testimony.

Genealogical information was shared, connections were made, and Reverend Nelson Hart provided so much valuable historical context that my notes were nearly indecipherable from trying to keep up with him. It was an emotional day: sharing information and building a more comprehensive and truthful picture of who these children were and what happened to them.

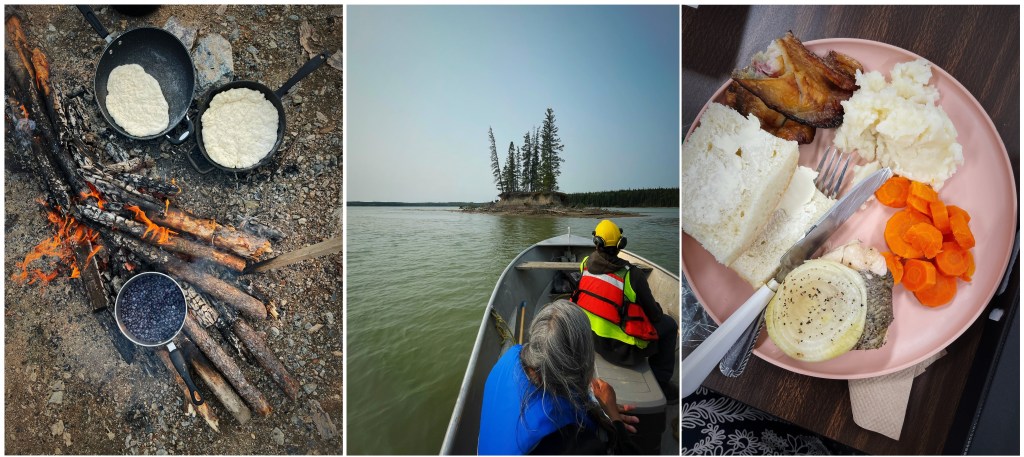

Alongside the heavy conversations, we also held space for joy, by sharing stories, meals (that smoked red sucker!) and good company together on the land. It is a profound privilege to do this work: to bear witness to the truth and to work collaboratively to tell it.

Ellen, Sarah, Florence and John are four of at least 70 children who died as a result of their forced attendance at Red Deer Industrial School. The Historic Resources Management Branch is honoured to be collaborating with twelve Survivor communities regarding the preservation and recognition of the Red Deer Industrial School cemetery.

Thank you to the descendants, Elders and Knowledge-Keepers from Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation for being so gracious with their time and knowledge. Thank you to Clifford Spence for sharing his testimony, and to Eva Linklater and William Elvis Thomas for their coordination efforts. Ekosi.

Sources

Gaudin, Samuel D. (1942). Forty-four years with the northern Crees. Toronto: Mundy-Goodfellow Printing Co.

National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. National Student Memorial for Red Deer Industrial School. Retrieved online from: https://nctr.ca/residential-schools/alberta/red-deer-industrial-school/.

Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation. (2016). Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation history: Respecting our past…Creating a bright future. Retrieved online from: https://www.ncncree.com/wp-content/uploads/2018-04-25-NCN-History-Book.pdf.

Red Deer Industrial Student Register, Provincial Archives of Alberta PR1979.0268/162.

Shipley, Nan. (1955). Anna and the Indians. Toronto: The Ryerson Press.

Banner image: “Part of the river near Red Deer Indian Institute.” Date unknown. Source: From Mission to Partnership Collection, United Church of Canada Archives.

My name is Arlene Emblau but my last name should have been Hamelin my father’s Baptismal last

name.

I have felt very sad that my farther was in one of the Government’s ‘scoops of the children and put in a Residential School . It explains a lot of why he was what he beame.

Mydfying 87 year old brother Robert Archie Emblau phoned me

from his dying bed in the General Hospital of Edmonton Alberta on the 13 March 2019. He told me that “he had something that should be told as it had been kept a secret for too long by him”.

I’m 85 years old now and after reading the stories here I still feel hollow and empty and too late.

I have tried to b find out where the Schools were in Alberta but

to no success.

Arlene Emblau/Hamelin

Hi Arlene, thank you very much for sharing your and your family’s story. There are interactive maps showing where residential schools operated in Alberta (and Canada) available through the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (https://nctr.ca/records/view-your-records/archival-map/) and Indigenous Services Canada (https://geo.sac-isc.gc.ca/ACPI-IRSMA/index_en.html).

You are also welcome to send me an email to discuss further at laura.golebiowski@gov.ab.ca. Take good care.