Editor’s note: September 30 is the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation and Orange Shirt Day. Reading residential school histories can be a painful process. If reading this is causing pain or bringing back distressing memories, please call the Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419. The Crisis Line is available 24 hours a day and can also provide information on other health supports provided by the Health Canada Indian Residential Schools Resolution Health Support Program.

The banner image above is “General view of the I.I. School.” Date unknown. Source: City of Red Deer Archives, P10890.

Written by: Laura Golebiowski (Indigenous Consultation Adviser) in collaboration with Whitecap Dakota First Nation.

In the late 1880s, a group of Dakota Oyate led by Chief Whitecap were making their home along the northern extent of their territory. They settled near Mni Duza—the South Saskatchewan River—on a landscape known as “Moose Woods”: rich with water, wood, wildlife and plants for sustenance and ceremony.

During Pàhiƞ śa śa waciƞ uƞyaƞpi (the War of 1812, or “When the Red Head Begged for Our Help”) the Dakota participated as allies to the British and were promised the protection of their lands and territory in exchange. But when the Wapaha Ska Dakota Oyate (contemporarily Whitecap Dakota First Nation) returned north of the Medicine Line a half-century later, these promises were not upheld by new Canadian colonial government. Dismissed as “American Indians,” the Wapaha Ska were excluded from Treaty, yet still subjected to policies of segregation: sequestered to reserve lands and forced to attend residential school.

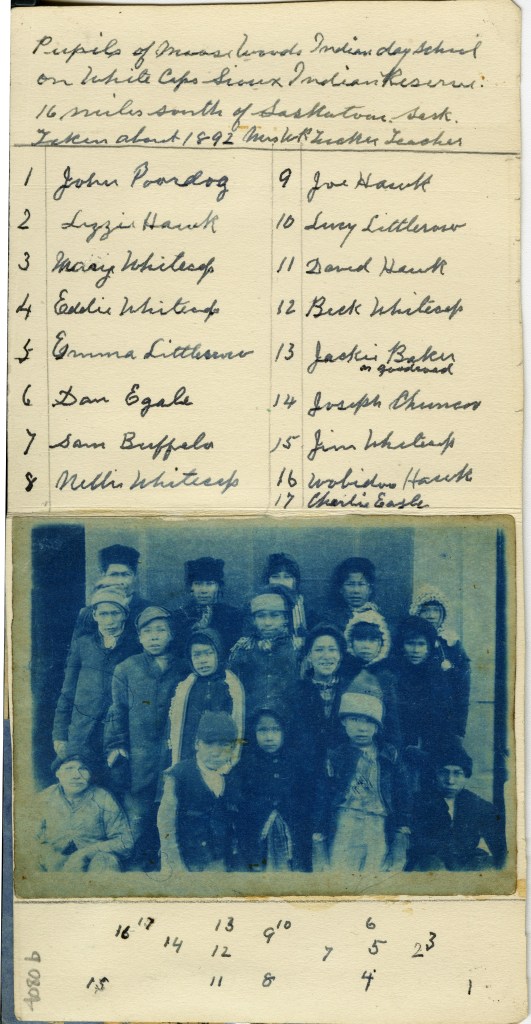

Children from Wapaha Ska were separated from their families, culture and territory and sent to schools in Regina, Duck Lake, Prince Albert, Lebret (Qu’Appelle), Elkhorn Brandon and Red Deer. Many of those children never returned home.

Charles Eagle (elsewhere named Charles Red Eagle), was born in 1876 and was admitted to Red Deer Industrial School on November 16, 1893 at the age of 17, though the school register erroneously states he was fourteen. He would have been one of the Red Deer Industrial School’s earliest students. With previous education at two Dakota day schools, Charles was regarded as a promising student and “anxious to be a teacher and a missionary.” Attendance at an industrial school was purported to be a means to further his studies.

Charles survived Red Deer Industrial School, and Brandon Industrial School, where he was sent following discharge from Red Deer in June 1895. By 1913, he was back home at Whitecap in the leadership role of Over-seer. Among his other responsibilities, Charles petitioned the government to re-open the day school within the community. He wrote:

…We do not wish to send our children to the Industrial School. We would rather have a school of our own on the Reserve…[We] do not want a priest to come to the reserve to get our children to go to Qu’Appelle [Indian Residential School] or elsewhere.

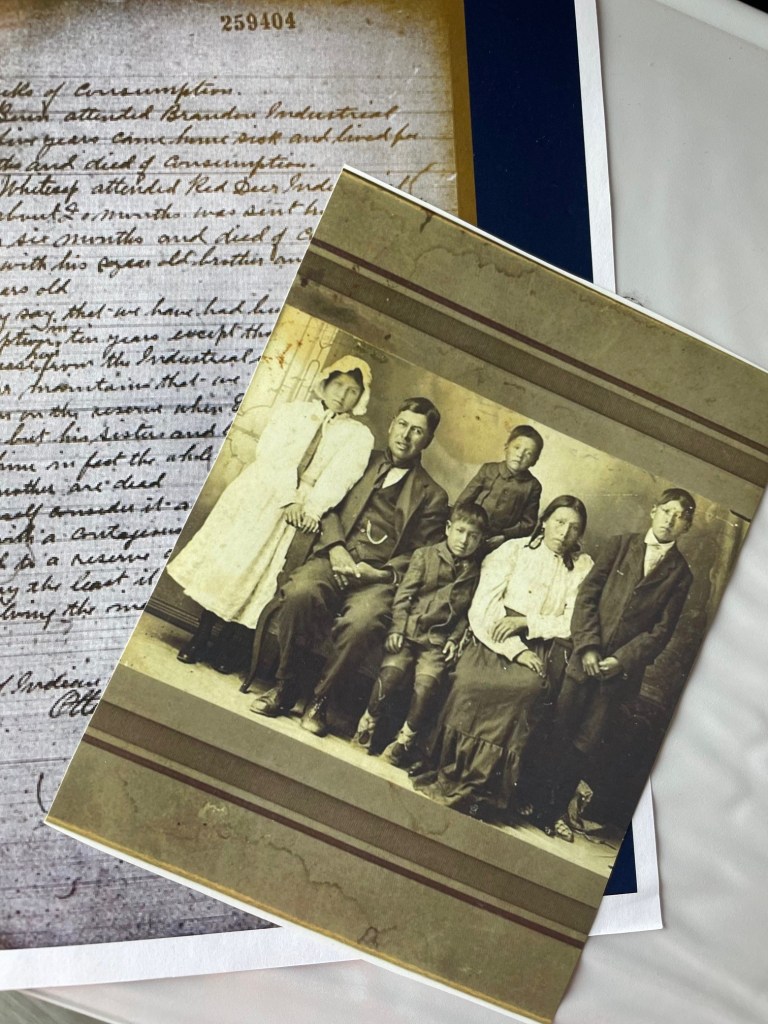

Charles married Mary Whitecap and together they raised several children. He died—still too young—in 1932 at the age of 56 and is buried in the old Whitecap cemetery. His grandchildren recall his stern personality; they wonder if the industrial schools made him that way.

Edward (Eddie) Whitecap was born in 1884; his grandfather was Chief Whitecap and his father was Chief Yanke Whitecap. He was taken to Red Deer in 1901. Though he was institutionalized for a short time, the archival record indicates that Eddie’s experience at Red Deer Industrial School included resistance, physical violence, and the illness that ultimately killed him and his family.

Eddie is named in a report by W. J. Chisholm, Inspector of Indian Agencies, who visited Red Deer Industrial School in the winter of 1903 in response to complaints of mismanagement lodged by a former teacher. Per the report, Eddie appears to have been subjected to corporal punishment from the school principal:

Yesterday the teacher overheard a boy of seventeen, Edward Whitecap, calling him (the teacher) a “bugger” and today, January 23, the same boy in school told the teacher to “go to hell.” The teacher proceeded to chastise the boy and the latter called on two other boys of about his own age to assist him. Fortunately the teacher dealt with him with such a dispatch that assistance was out of the question. The teacher then properly reported the case to the Principal who administered a formal punishment, moderately severe though it might have been done in a much more effective manner.

Eddie’s date of discharge from Red Deer Industrial School is June 30, 1903. The principal’s remarks only state: “dead.” With such scant information in the school register, one might assume he was buried in the school’s cemetery. However, through collaboration with Whitecap Dakota Nation, a more comprehensive and truthful picture of what happened to Eddie and his family emerged.

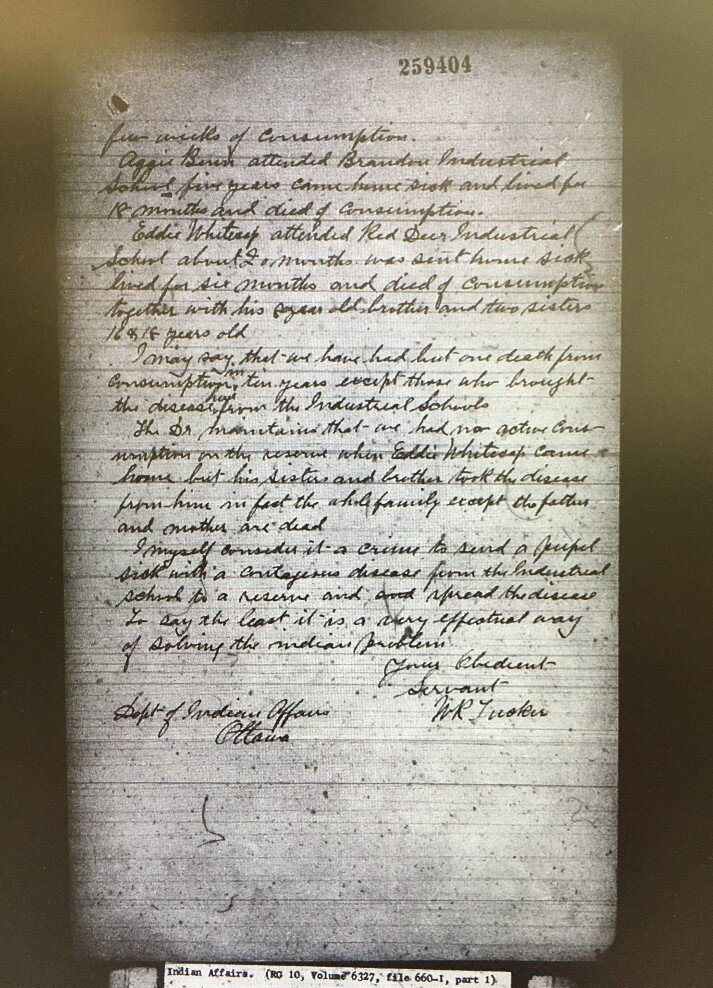

Councillor Frank Royal provided a copy of a letter written on May 26, 1904 by W.R. Tucker, the teacher at Whitecap’s day school. He wrote the Department of Indian Affairs to raise awareness of the harms of the residential school against Whitecap Dakota Nation children. His letter sharply protests against the residential school system:

As the Qu’Appelle Industrial School has been destroyed by fire—doubtless there will be discussions as to the advisability to rebuilding it—I thought perhaps my 16 years of teach[ing] and observations of Indians may be of some use to you in deciding what is best – to rebuild or not…

Eddie Whitecap attended Red Deer Industrial School about two months, was sent home sick, lived for six months and died of consumption together with his 8-year-old brother and two sisters, 16 and 18 years old.

…The doctor maintains that we had no active consumption on the reserve when Eddie Whitecap came home but his sisters and brother took the disease from him; in fact the whole family except for the father and mother are dead.

I myself consider it a crime to send a pupil sick with a contagious disease from the industrial school to a reserve and spread the disease. To say the least it is a very effectual way of solving the Indian problem.

Eddie is not buried in the school cemetery; he is buried in his home community, but his forced attendance at Red Deer Industrial School irrefutably killed him. Moreover, it brought disease home to his family and community, killing not only Eddie, but his siblings: Nellie, Becky and his younger brother. Their names are not listed in the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation’s Memorial Register. Should they be? And how do we honour the memory of children who died, but whose graves are located in multiple different locations across the prairies?

Whitecap Dakota First Nation works hard to reconnect to the language and culture that was taken from them. Whitecap’s Residential Survivors Group is dedicated to promoting healing and honouring Nation members who attended residential school. On the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation in 2024, the Survivors Group unveiled the community’s residential school monument, paying tribute to the, “determination, perseverance and courage of all student Survivors and their families.”

Charles Eagle and Eddie Whitecap are two of more than 350 children who were institutionalized at Red Deer Industrial School between 1893 and 1919. At least 70 children died as a result of their forced attendance. The Historic Resources Management Branch is honoured to be collaborating with Survivor communities regarding the preservation and recognition of the Red Deer Industrial School cemetery.

Thank you to Councillor Frank Royal, Senator Vivian Anderson, Crystal Buffalo, Cynthia Bear, Lori Buffalo-DeLaRonde and Rachel Littlecrow for their ongoing collaboration and guidance. Thank you to the descendants of Charles Eagle, especially Colette Eagle, for helping share their grandfather’s story. Pidamayaye.

Sources and Further Learning:

Danyluk, Stephanie, Max Faille, Jarita Greyeyes and George Rathwell. (2017). Wa Pa Ha Ska: Whitecap Dakota First Nation. Retrieved online from https://dakotalessons.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/WaPaHaSKa-book.pdf.

Dominion of Canada. (1893). Annual report of the Department of Indian Affairs for the year ended 30th June 1893. Government of Canada. Retrieved online from https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/aanc-inac/R1-90-1893-eng.pdf.

Duck Lake Agency – Moose Woods Sioux School – Teachers – General Administration. RG 10, Volume number: 6295, File number: 625-1, part 1 (Part of subseries: R216-247-1-E). Library and Archives Canada.

General correspondence relating to the Red Deer Industrial School from its inception, 1889-1912. RG10, Volume number: 3920, Microfilm reel number: C-10161, File number: 116818. Library and Archives Canada.

Red Deer Industrial Student Register, Provincial Archives of Alberta PR1979.0268/162.

Royal, Frank and Stephanie Danyluk. (2021). Our new legacy: Residential school survival at Whitecap Dakota First Nation. Saskatchewan History and Folklore Society. Retrieved online from https://www.skhistory.ca/blog/our-new-legacy-residential-school-survival-at-whitecap-dakota-first-nation.