What makes your holiday season complete? Is it fruit cake, latkes or bannock? Lighting a menorah, Christmas tree or a kinara? How old or new are the traditions you participate in? Where did they originate?

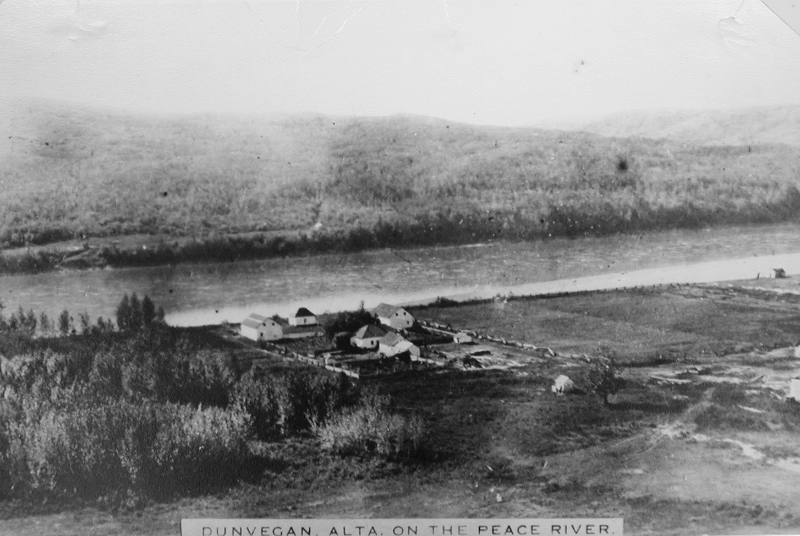

The Beaver people who first inhabited the areas bordering the Peace River have been gathering at Dunvegan for thousands of years. Like other Indigenous peoples, before the arrival of the fur traders and missionaries, it’s possible they may have celebrated the Winter Solstice while camping in the area.

When Northwest Company fur traders arrived in 1805 and established Fort Dunvegan, they brought with them the customs of European Christians, particularly those of the Scots. You’ve probably heard of Kwanzaa, but have you ever heard of Hogmanay? In Scotland, Christmas was celebrated quietly, while Hogmanay or New Year’s Eve, was well…a party! Being as many fur traders originally hailed from Scotland, those traditions came with them over to what is now known as Canada.

Indeed, this is reflected in the journals left by the men in charge at Fort Dunvegan through the 1800s. In some cases, Christmas isn’t even mentioned at all on December 25. When it is mentioned it’s often to say that nothing of importance happened. But every entry that was made on January 1 (at least between 1822 and 1844) mentions everyone gathering at the fort for their usual treat of a ration from the store. This included gifts of tobacco, rum, meat or biscuits. Even lime juice has been mentioned as a special treat given to visitors.

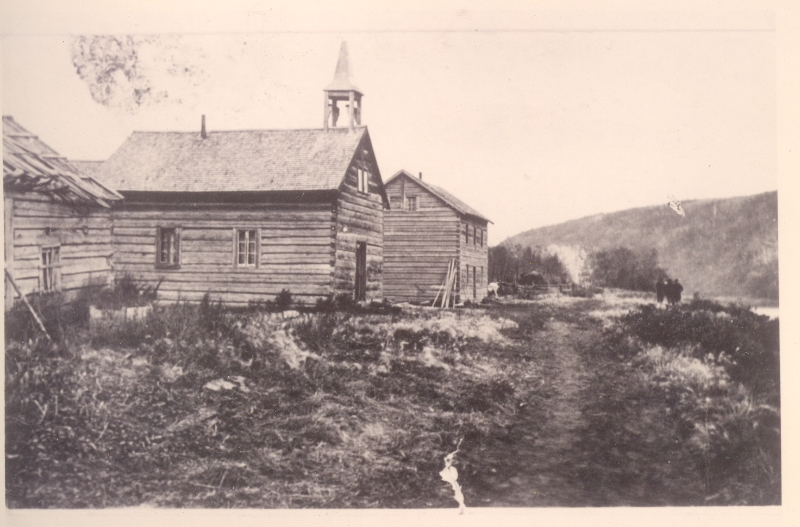

That’s not to say that Christmas wasn’t celebrated at all. With the founding of the St. Charles Catholic mission at Dunvegan in 1867, community members had a place to go to celebrate mass. When the church was built in 1886, it is highly likely that the priests would decorate it for Christmas with boughs and young evergreen trees with candles hung on them, and of course a nativity scene. One journal entry on Christmas 1897 said that it was a glorious day and everyone was off to church. Even the Protestants of the community went to the Catholic church.

Dances were often held on both Christmas and New Year’s at Fort Dunvegan. On Christmas Day, 1897, Albert Tate, the man in charge, recorded in the fort journal, “We are to have a dance tonight, but as it is Saturday of course we will stop at or before Sunday. At least the ‘Boys’ say they will.” It is known that Albert played fiddle and his wife Sarah not only had a formidable singing voice, but also was a master of the Red River Jig. One source describes: “Endurance is a sign of merit in the Red River jig. A man or woman steps into the limelight and commences to jig, a dark form in moccasins slips up in front of the dancer, and one jigs the other down, amid plaudits for the survivor and jeers for the quitter.” Apparently, Mrs. Tate could out-jig anyone!

And what of trees, cards and gifts – the trimmings of Christmas we’re most familiar with today? Unfortunately, there is no hard evidence of these items at Dunvegan, or what they might have looked like. But a few clues can lead us to make some educated guesses. When restoring the Factor’s House, crews found pine needles between the baseboard and the walls which may indicate that Christmas trees were in use at Dunvegan. Christmas trees had become popular in the later 1800s thanks to the trendsetting Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert (who brought the tradition from his native Germany). There is evidence that candle holders for Christmas trees were manufactured in Fort Chipewyan in 1890, so it’s not unlikely that Dunvegan may have received some of these decorations.

Christmas cards became commercially available in Britain in 1843 and then in America in the 1870s. By the 1880s, one company was producing five million cards per year. It is likely that in the 1890s, the Tate family would have received and/or sent at least a few Christmas cards.

As for gifts, the Tate children were probably quite lucky. Mrs. Tate was well-known for her handy work in activities like sewing, beading and lace making. Mr. Tate enjoyed woodworking and, as the man in charge at Fort Dunvegan, had ready access to the HBC catalogue. Perhaps a new pretty dress, or a carved top would have been under the tree for the children on Christmas morning.

While holiday traditions vary from person to person and change through time, many celebrations include common themes such as sharing food, gifts, and light with others. Certainly, this has been the case in the area now known as Dunvegan over the years.

Sources

Cameron, Agnes Deans. The new North: being some account of a woman’s journey through Canada to the Arctic. New York & London: D. Appleton & Co, 1909.

Larmour, Judy. St. Charles Catholic Mission: A Narrative History, 1867-1903; Material History of St. Charles Mission; Material History of the H.B.Co Factor’s House (1877-1900). Prepared for the Fort Dunvegan Historical Society and Alberta Culture and Multiculturalism, December 1990.

Leonard, David W., and Michael Payne, eds. Dunvegan Post Journals for 1822 to 1830; Dunvegan Post Journals for 1834-1845. Peace Heritage Press, 2016; 2019.