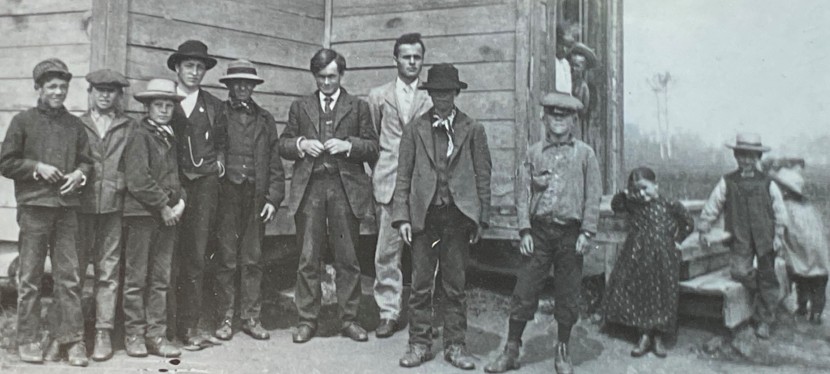

Editor’s note: The banner image above is of the school children of Pakan in 1910, the year before the 1911 census. Image donated by Rev. Metro Ponich.

Written by: Sarah Mann, Master’s student in Anthropology, University of Alberta

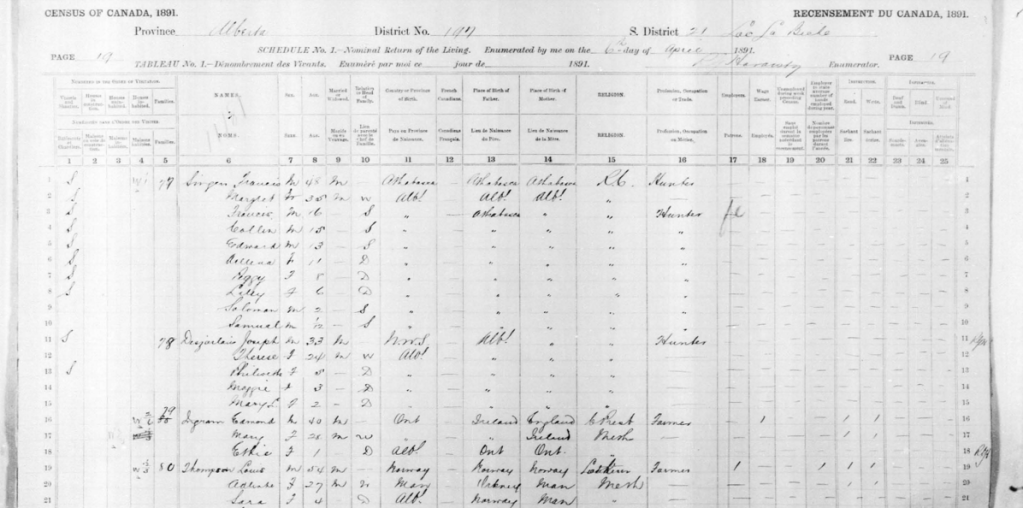

The Canadian census is something most Canadian adults have experienced. While the survey is often looked as tedious, it can hold a myriad of information and questions. My work around Victoria Settlement Provincial Historic Site was done as part of a Community Service Learning (CSL) internship with the Heritage Division of the Government of Alberta. This work involved looking at what information and further research plans can be drawn from the Victoria Settlement censuses using supplemental materials from community history books from around Alberta. From the census data, I created two spreadsheets tracing the changes and differences in the various censuses done in Victoria Settlement. Comparisons of the 1881, 1891 and 1901 censuses show several inconsistencies and allow us to ask many questions about life in the area.

Victoria Settlement, northeast of Edmonton along the North Saskatchewan River, was settled in 1862 when George McDougall founded the Methodist mission on the site of a traditional Indigenous camping ground. Then in 1887, the area became known as Pakan after the name of the local post office, which in turn was named for Cree Chief Pakan (James Seenum). The settlement was abandoned in 1922 when the railroad bypassed the community, instead being built through the town of Smoky Lake, approximately 15 km to the north. The eras examined in the censuses are the periods of 1881-1911, as there is a national census every 10 years. In between the years of 1891 and 1901 a large Ukrainian population settled in the area, but my study focused on the Métis elements of the community.

Read more