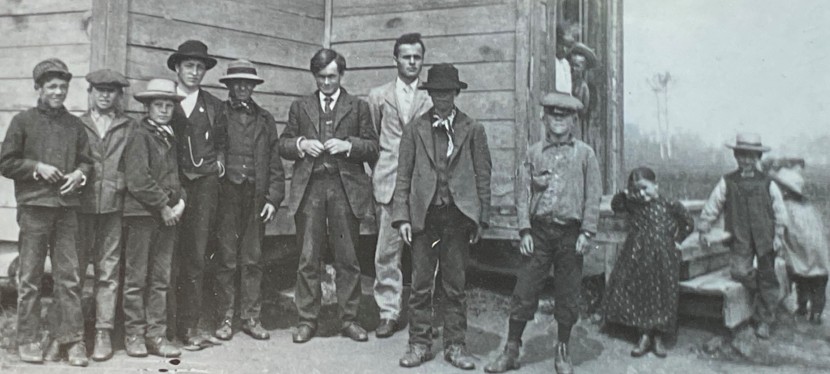

Editor’s note: The banner image above is of the school children of Pakan in 1910, the year before the 1911 census. Image donated by Rev. Metro Ponich.

Written by: Sarah Mann, Master’s student in Anthropology, University of Alberta

The Canadian census is something most Canadian adults have experienced. While the survey is often looked as tedious, it can hold a myriad of information and questions. My work around Victoria Settlement Provincial Historic Site was done as part of a Community Service Learning (CSL) internship with the Heritage Division of the Government of Alberta. This work involved looking at what information and further research plans can be drawn from the Victoria Settlement censuses using supplemental materials from community history books from around Alberta. From the census data, I created two spreadsheets tracing the changes and differences in the various censuses done in Victoria Settlement. Comparisons of the 1881, 1891 and 1901 censuses show several inconsistencies and allow us to ask many questions about life in the area.

Victoria Settlement, northeast of Edmonton along the North Saskatchewan River, was settled in 1862 when George McDougall founded the Methodist mission on the site of a traditional Indigenous camping ground. Then in 1887, the area became known as Pakan after the name of the local post office, which in turn was named for Cree Chief Pakan (James Seenum). The settlement was abandoned in 1922 when the railroad bypassed the community, instead being built through the town of Smoky Lake, approximately 15 km to the north. The eras examined in the censuses are the periods of 1881-1911, as there is a national census every 10 years. In between the years of 1891 and 1901 a large Ukrainian population settled in the area, but my study focused on the Métis elements of the community.

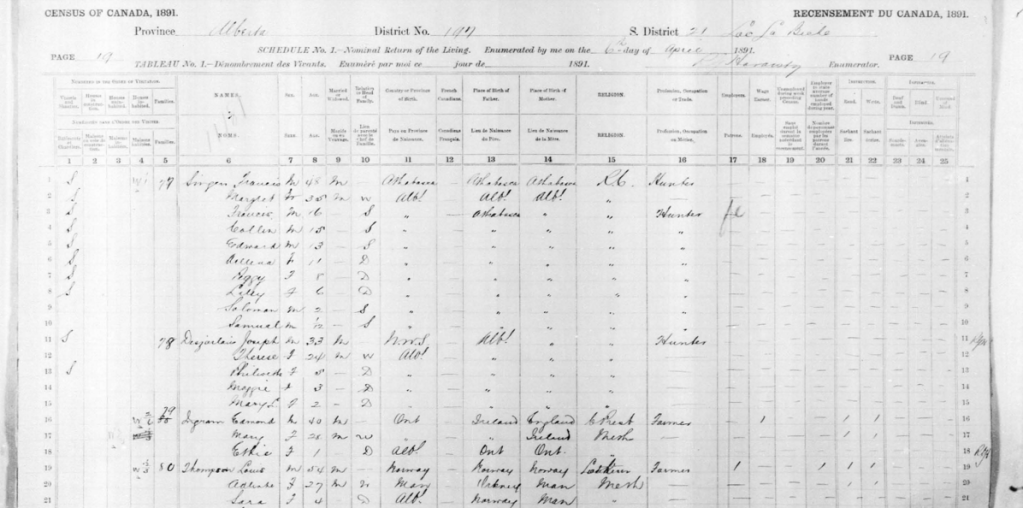

The biggest questions surround the identification of ethnicities of the families and people living in Victoria Settlement. At this point, we are uncertain whether individuals were self-reporting their ethnic identity, or whether census-takers assumed and assigned ethnic markers to residents. Either way, ethnic markers for specific individuals changed between censuses. The 1881 census shows that most families were identified as English or Scottish. Only 20 years later in 1901, the same families are listed as “English half breeds” and “Scottish half breeds”; therefore, the whole town was being identified as having mixed ethnic heritage. Then in 1911, those same families switched back to the identifiers of English and Scottish. The figure below shows how four individuals in this community are identified differently. If the parents have two different ethnic markers, then the children will inherit the ethnic markers of their father, with the one exception of the Thompson family where the children inexplicably take the mother’s ethnicity.

It is important to note here that changing political and social circumstances changed understandings and implications of mixed heritage or Métis identity and who identified as such. Historical events like the Battle of Batoche in 1885 and the western of expansion of Canada were huge changes and impacted government policy between the Métis peoples and the federal government. The way in which ethnicity was recorded reflected these changes in government policy, though government policy likely had little impact on how Victoria Settlement locals viewed their own ethnicity. Interestingly, scrip (money/land coupons received from the Canadian government in return for giving up land rights) came into the area in the 1880s-1920s, and to be considered for scrip, you needed to be seen as a “half-breed”. Records suggest that many Victoria Settlement residents took scrip.

Comparing four decades of census documents show families and peoples both leaving and coming to Victoria settlement and the area. There are questions, however, about where families go afterwards. In looking at the community history book of Smoky Lake, we can see that many families only established themselves there for a few years. These families then moved into the Whitford Settlement close to Lac la Biche in the 1930s. This has us asking multiple questions: where did they go other than Whitford Settlement and Smoky Lake? Why did they not move to Smoky Lake? How can we trace them beyond 1930?

This research has demonstrated that there is still much to learn about the Métis community who once inhabited Victoria Settlement. There is room for further exploration through techniques employed by Métis thinkers doing similar work, such as kinmapping by Paul Gareau. This involves using records such as scrip records, census records and church records in order to trace the movement of a family across Canada. The next steps revolve around comparing the land of Victoria Settlement and where the people left after the dissolution of Victoria Settlement (primarily Lac La Biche and Kikino Métis Settlement area) to see if it suggests patterns of migration after the settlement’s dissolution. The censuses of Victoria Settlement can give us important insight and understanding of the people who called the land of Victoria Settlement home.

Sources

Adese, Jennifer. ““R” Is for Métis: Contradictions in Scrip and Census in the Construction of a Colonial Métis Identity.” Topia: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies 25, no. 1 (2011): 203-212.

Andersen, Chris. “Métis” : Race, Recognition, and the Struggle for Indigenous Peoplehood. UBC Press, 2014.

“Census of 1881, Province of Battleford N.W.T District No. 192,Victoria Mission, 04 April 1881” From Government of Alberta.

“Census of 1891, Province of Alberta District No. 197, Sub District No. Lac La Biche, 6th April 1891” From Government of Alberta.

Chabot, Joseph “Census of 1901, Province of N.W.T District No. 202 Alberta, Sub district No. 131 Pakan” From Government of Alberta.

Gareau, Paul. Metis Kinscapes: Researching Metis relations and Peoplehood at Lac Ste Anne, Ab Research Proposal SSHRC. 2018.

Hurt, Leslie J. The Victoria Settlement : 1862-1922. Historical Sites Service. Occasional Papers: 7. Alberta Culture Historical Resources Division, 1979.

Lac La Biche Historical Society. Lac La Biche: Yesterday and Today. Lac La Biche Historical Society 1975.