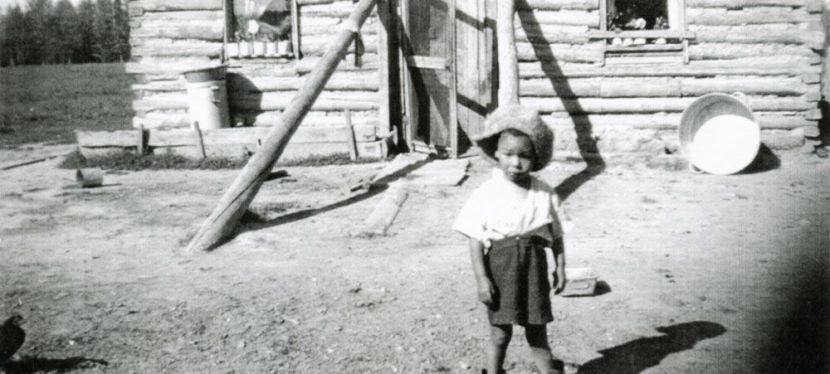

Editor’s Note: February is Black History Month, a time to honour the legacy of Black Canadians and their communities. Throughout the post below are excerpts of the poem “Our Pioneers” by Gwen Hooks, appearing in the book The Keystone Legacy: Recollections of a Black Settler. The banner image above is Ron Smith, grandson of Elizabeth Hayes, in front of the Hayes family home. Breton, Alberta, circa 1950. Credits: Nellie Whalen, Breton and District Historical Museum.

Author’s note: I am grateful to the past work of the Breton and District Historical Society, who have made these compelling histories so accessible to the public through various public awareness initiatives. This post greatly relies Gwen Hook’s excellent book The Keystone Legacy: Recollections of a Black Settler. I would also like to express my gratitude to Allan Goddard of the Breton and District Historical Museum for being so gracious with his time and knowledge.

Written by: Laura Golebiowski, Indigenous Heritage Section

The Black Pioneers to a new land came,

Around the year of nineteen ten,

Oklahoma and Kansas they left behind

A strange new life to begin.

As heritage professionals, it seems an unwritten rule that we must stop and read every historic interpretive sign we pass. It was in this way I was first introduced to the story of Keystone, driving home from Paul First Nation in the summer of 2021. The big blue highway sign spoke of a distinctive community built by Black families who arrived in the area from Oklahoma in the spring of 1911.

I was familiar with the story of Amber Valley, understood to have been the largest Black settlement west of Ontario. I quickly learned, however, that Amber Valley was only one of several Black-founded communities in western Canada at the turn of the century. Others included Wildwood (east of Edson), Campsie (northwest of Edmonton), Maidstone (in west-central Saskatchewan), and Keystone, now named Breton, located southwest of Edmonton.

They left a country so warm and rich,

With fruit plus nuts and grain,

They chose Alberta that was rugged and cold,

Huge trees covered the rough terrain.

The origin stories for these communities are much the same. A chain reaction of land dispossession saw the settlement of Indian Territory, forcing the removal of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Seminole Peoples from their lands. Oklahoma statehood introduced Jim Crow laws and segregation, making the area incredibly dangerous for the Black families already residing in the new state. Thus began the Black migration north: from 1905 to 1912, between 1,000 and 1,500 African Americans moved to western Canada from the United States in search of a better life. However, upon arrival, pervasive racism in city centres prompted Black settlers to establish roots in rural areas.

Read more →