Written by: Fraser Shaw, Heritage Conservation Advisor and Allan Rowe, Historic Places Research Officer

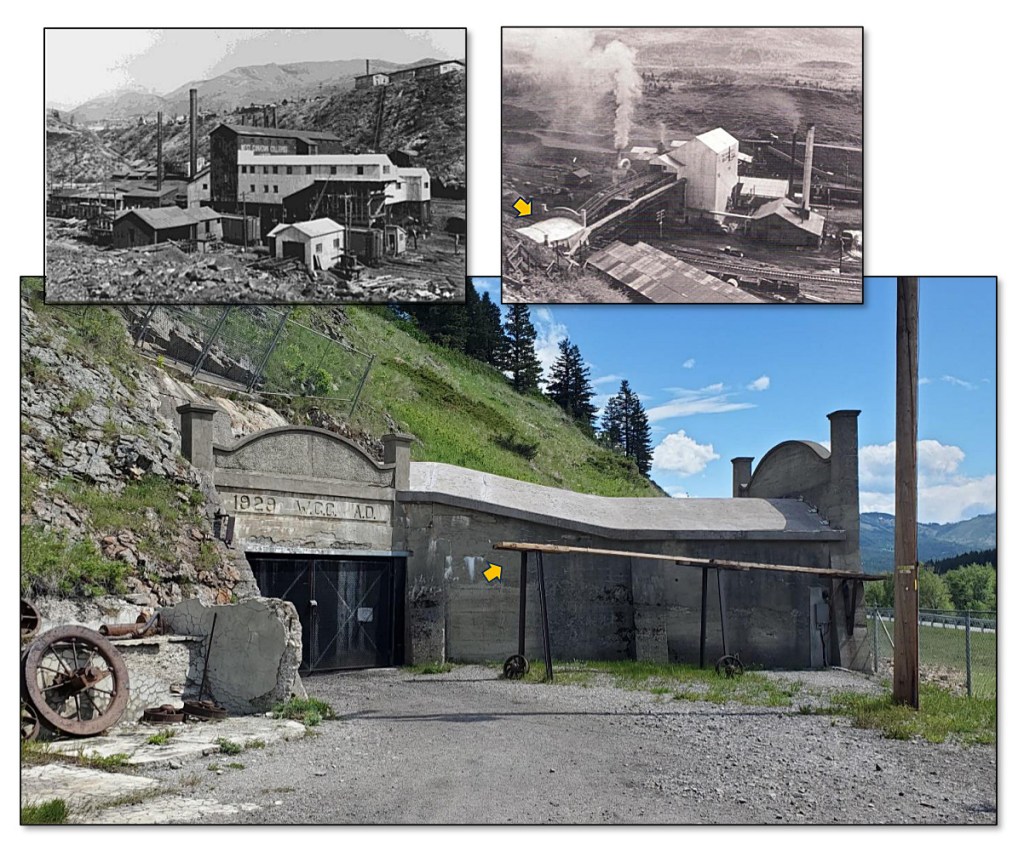

The Crowsnest Pass is a landscape of remarkable history and exceptional natural beauty in southwest Alberta. Highway 3 winds through the mountain corridor past the former site of the West Canadian Collieries Mine, where an enormous tipple once straddled rail spurs on what is now the highway. The tipple and above-ground operations were dismantled after the mine’s closure in 1961 but the distinctive concrete portals remain and are clearly visible from the road. Now a historic site, the Crowsnest Pass Ecomuseum Trust Society owns and operates an interpretive facility and maintains a portion of the main tunnel where public tours and thousands of visitors experience an underground mine that historically extended for kilometres along the coal seams.

Designated as a Provincial Historic Resource in 2011, the former mine exemplifies the early mining history of the Crowsnest Pass and represents industrial practices and technologies at one of Alberta’s most significant underground mining operations in this important historic coal-producing region.

The West Canadian Collieries Mine is strongly associated with the rich history of coal mining in the Crowsnest Pass. The industry emerged in the region after the dramatic growth of railways in late-nineteenth century Alberta created demand for a regional supply of coal for fuel. To meet this demand, in 1898 the CPR built a branch line west from Lethbridge to the eastern Crowsnest Pass, an area abundant in suitable coal resources. This sparked a flurry of investment as no fewer than 11 corporations began coal mining operations in the region between 1900 and 1909. Among the most successful was West Canadian Collieries Ltd., established in 1903 by French businessmen Jules Justin Fleutot and Charles Remy. The new company acquired over 20,000 acres of coal leases and opened mines in Lille, Bellevue and Blairmore in the early 1900s, making it one of the largest coal mining concerns in Alberta. By August 1905, there were 150 miners on the West Canadian Collieries payroll at Bellevue.

As was typical of the Crowsnest Pass, the workforce at the West Canadian Collieries Mine was largely immigrant and featured a diverse group of workers from around the world. Data from the 1911 Census of Canada reveals the largest group of miners in Bellevue came from England (34%) and Italy (26%), but the town was home to Scottish, Russian, Finnish, Ukrainian, Belgian, Hungarian, German, Polish, Swedish and Icelandic miners as well. Two decades later, workers from Great Britain (21.5%) and Italy (13%) continued to comprise the largest proportion of Bellevue miners, though the data also reveal a significant proportion of Slovak (11.5%) and Polish workers (11%) by the early 1930s. The ethnic composition of the workforce shaped the society that emerged in the town of as well – one teacher at the Bellevue School described her classroom as a “League of Nations,” with several dozen nationalities represented.

Coal mining was an extremely hazardous profession on the early 1900s – at least 1,000 workers died in accidents and explosions in the region’s coal mines between 1907 and 1945, while thousands more suffered significant injuries. Underground coal mining in the Crowsnest Pass was especially hazardous due to high concentrations of explosive methane gas that occurred naturally because of the region’s geology. On 9 December 1910, a falling rock ignited a powerful explosion in West Canadian Collieries Mine crippling the ventilation system and precipitating the formation of the poisonous gases known as afterdamp. An experienced mine rescue team was brought in from Hosmer, British Columbia, to search for survivors. In the end, 30 miners and one rescuer died, making the 1910 mine explosion in Bellevue the largest industrial disaster in Alberta’s history until it was eclipsed by the Hillcrest Mine Disaster of 1914.

Dangerous working conditions, along with low wages, were key factors contributing to the strength of organized labour in Bellevue. The miners at West Canadian Collieries Mine were members of District 18 of the United Mine Workers of America (organized in 1903) and by 1919, there were 426 unionized coal miners in Bellevue. Union membership soared in the 1910s as did coal production, in large part due to the huge increase in demand for coal during World War One. The miners won significant wage increases between 1916 and 1919 but those gains were threatened by inflation, high unemployment and a post-war economic slump in Alberta. Mining companies launched a campaign to scale back wages and other workers’ gains, triggering, “the sharpest and most sustained class conflict” in the region’s history between 1922 and 1926. A series of strikes broke out as workers resisted wage cuts and demanded company recognition of the miners’ new union, the militant United Mine Workers of Canada, established in 1925. The situation grew worse with the onset of the Great Depression as production at the Bellevue Mine declined by 54.8% between 1929 and 1931. In 1929, the West Canadian Collieries Mine only operated for 173 days, placing enormous economic strain on miners and their families.

The bitter struggles of the 1920s, coupled with the economic pressures of the Great Depression, set the stage for one of the largest industrial disputes in Alberta’s history, the Pass Strike of 1932. The strike was triggered by the arbitrary dismissal of a worker at Greenhill Mine, though the conflict reflected a larger struggle by workers to hold the line against further wage rollbacks. Workers walked off the job in Blairmore and Bellevue in February 1932 in a show of solidarity with the dismissed worker, while workers in Coleman joined the strike in March 1932. The strike lasted seven months and was marked by significant violence (described by Seager as “guerilla warfare in and around the collieries”) between strikers, strikebreakers and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Striking miners were blacklisted and mine owners and prominent, wealthy citizens engaged in a “vicious campaign of political racism” as Eastern European immigrant workers were smeared as foreign communist agitators. The result of the strike was a stalemate, though Seager notes that the workers had successfully held the line:

Sparked by petty tyranny on the part of the employers and prolonged by their desire to smash the last vestige of miners’ independence, the strike can be regarded as an exercise in futility…The miners were not broken and by their firm resistance they showed the line beyond which they could not be pushed.

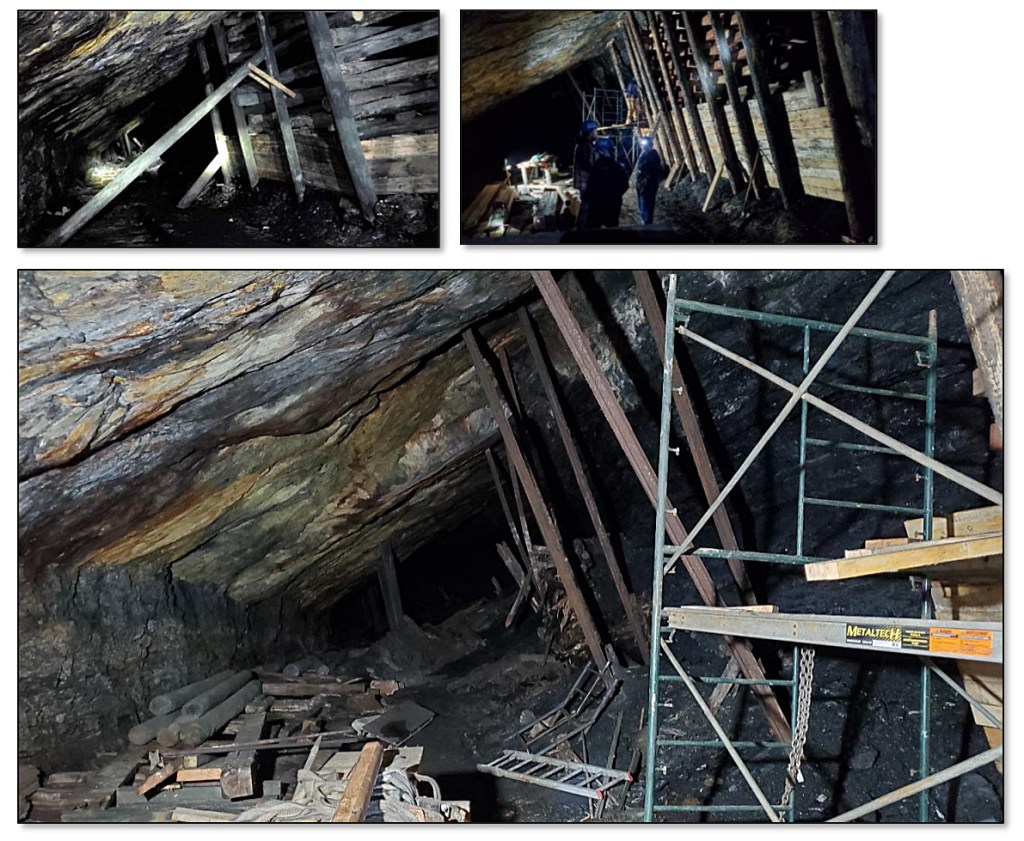

The West Canadian Collieries Mine remained open for nearly 30 years after the end of the 1932 Pass Strike. During the nearly six decades of its operation, the Bellevue mine participated in the evolution of “room and pillar” mining practices and technologies. Early twentieth-century mining with hand picks and chest augers was replaced in the 1920s by air picks that reduced the risk of explosion for a safer work environment and increased production. Industry-wide mechanization in subsequent decades to boost efficiency and help underground mines compete with emerging open pit and strip mines was in fact limited at Bellevue due to the steep pitch of the coal seams, which restricted heavy equipment to level tunnels. The transition from steam to diesel locomotives after the Second World War led to a precipitous decline in coal demand and forced the mine’s eventual closure in 1961. From 1903 onward, workers extracted roughly 13 million tonnes of coal, virtually all of it purchased by the CPR.

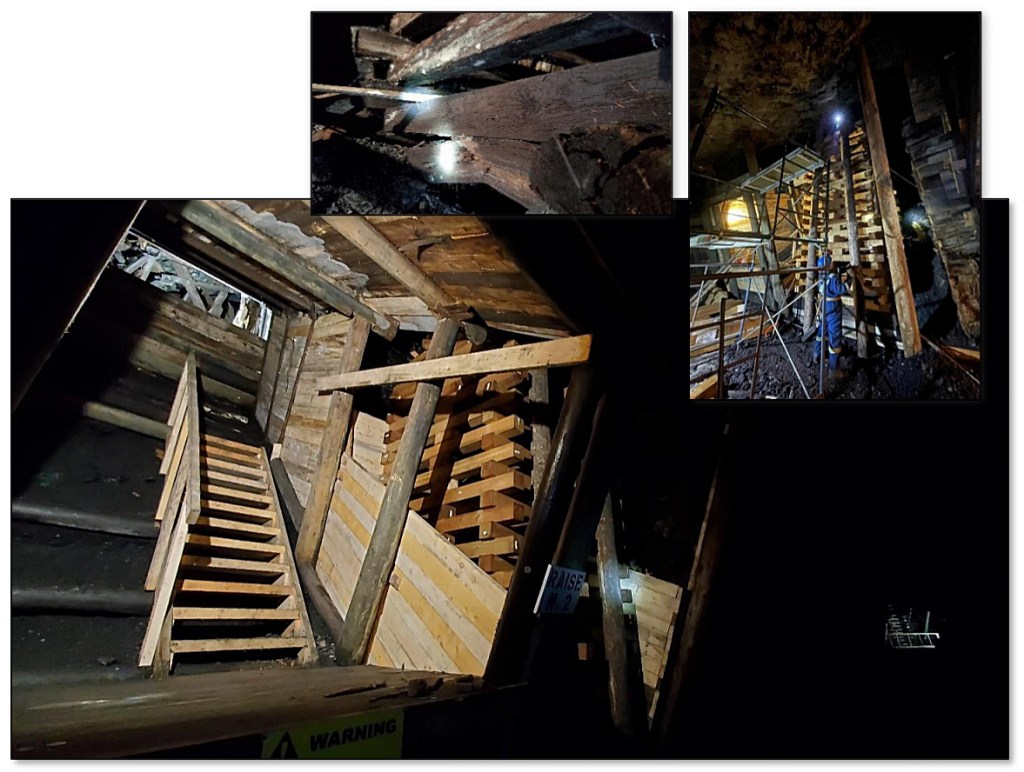

The site today reflects changes in the industry from circa 1900 to 1960 and retains many essential underground mine features of the period. These include the iconic 1929 portals embellished with concrete piers and arched parapets and approximately 300 metres of the main tunnel stabilized for public access. Exposed coal seams, heavy timber cribbing with steel rail and wood roof supports, and views into lateral tunnels and chutes clearly represent the “room and pillar” system of mining.

Public safety is foremost in operations and maintenance at the Bellevue Underground Mine. An elaborate system of protocols includes daily mine inspections; tours are led by experienced guides; and all visitors are equipped with miners’ hardhats and battery-powered lamps. Maintenance in the mine is ongoing, as it was historically, and all work at this Provincial Historic Resource follows the Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada. This work is possible through the skill and dedication of staff and a team of volunteers, some of whom are themselves former miners.

The West Canadian Collieries Mine represents the gamut of conservation treatments that include preservation of existing fabric and structures; rehabilitation or adaptation of historic elements for safety and practical reason; and restoration of irreparably deteriorated or missing elements based on physical and other evidence. Preservation protects, stabilizes and maintains historic or “character-defining” elements as much as possible and is fundamental to all heritage conservation. A guiding principle is to preserve integrity by doing as little as possible but to consider as much work as necessary for a viable resource with a compatible continued use.

The retention of thick, tree-like timbers at the No. 1 Seam near the tunnel entrance, which date to the mine’s years of operation, is a preservation approach where no intervention occurs beyond simply protecting the elements from harm. However, such minimal intervention is challenged at this former industrial site by adverse underground conditions that historically caused, and continue to cause, rapid and inevitable decay, from rotting timbers to collapsing coal faces.

A rehabilitation approach sensitively adapts materials and construction methods as needed for safe occupancy by workers and the public. Examples include replacing unsafe rotted timber with new preservative-treated wood of similar dimensions and overall appearance. Massive Douglas-fir logs originally shipped by rail from nearby British Columbia are now difficult to source and are challenging and dangerous for a small volunteer crew to maneuver. New, more slender treated logs supporting the heavy board “lagging” lining the tunnel wall maintain the historic appearance but dramatically slow decay in the chronically wet environment. Such practical considerations are critical where a former industrial site is sustained by visitor revenue rather than mining. These changes are unlikely to be obvious to visitors but are carefully documented and considered in advance. The adaptations themselves can be used to interpret historic mining practices.

In heritage conservation, a restoration treatment reveals, recovers or accurately represents hidden or missing historic elements to restore an earlier period of a site’s history. Restoration is in fact uncommon at most historic sites but is pervasive, if subtle, at the Bellevue mine. In the decades since the mine’s closure, ongoing natural sloughing of the coal face along the main tunnel led to re-lining of the upslope wall with new timber over old, eventually narrowing the tunnel by as much as two metres. Physical evidence such as post holes combined with an understanding of historic mine operations helped to determine the original tunnel dimensions. Re-lining of the tunnel that is now underway removes many tons of debris and reinstates the original width using materials and assemblies based on traditional mine construction.

These interventions all rely crucially on the knowledge and skills of the volunteer team. Their ongoing practice and adaptation of traditional mine construction methods maintains a form of intangible cultural heritage that intertwines with conservation of the physical attributes of the mine itself.

Sources

Babian, Sharon. “The Coal Mining Industry in the Crow’s Nest Pass.” Edmonton: Alberta Culture, 1985.

Buckley, Karen. Danger, Death, and Disaster in the Crowsnest Pass, 1902-1928. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2004.

Chambers, Allan. Spirit of the Crowsnest: The Story of Unions in the Coal Towns of the Crowsnest Pass. Edmonton: Alberta Federation of Labour and Alberta Labour History Institute, 2012.

Larmour, Judy. “Crowsnest Pass Historical Driving Tour: Bellevue and Hillcrest.” Edmonton: Alberta Culture and Multculturalism, 1990.

Seager, Allen. “A Proletariat in Wild Rose Country: The Alberta Coal Miners, 1905-1945.” PhD diss., (York University, 1981).

Seager, Allen. “Socialists and Workers: The Western Canadian Coal Miners, 1900-21.” Labour/Le Travail 16 (1985): 23-60.

Seager, Allen. “The Pass Strike of 1932.” Alberta History 25, no. 1 (1977): 1-11.

What a fabulous piece on the Bellevue Mine and mining in the Crowsnest in general. Thank you Fraser. Sharp as ever lad.

Ian C.

And thanks to Allan as well!!!