Wishing everyone a safe and enjoyable holiday season! The images below, courtesy of the Provincial Archives of Alberta, were taken from the John Glascow Family Christmas, Edmonton, 1963.

Editor’s note: All images in this post were taken by Suzanna Wagner. The image above is of a view across the Stromness Harbour, Orkney.

Written by: Suzanna Wagner, Program Coordinator, Victoria Settlement and Fort George & Buckingham House

Have you ever travelled vast distances only to find pieces of home?

Intent on exploring new vistas, seeing the ocean, and walking through Neolithic sites, this Canadian historian jetted off to Orkney, Scotland for a vacation. Orkney and Canada share a strong historic connection since the Hudson’s Bay Company hired a great many of their labourers from Orkney. Working with fur trade history made me aware of this, but the only concession my trip plan made to the Orkney-Canada connection was an as-of-yet unread copy of Patricia McCormack’s paper, “Lost Women: Native Wives in Orkney and Lewis” tucked into my suitcase.

After three flights, I arrived bleary-eyed on the largest island of this archipelago north of the Scottish mainland, feeling as though I had travelled to a rather remote part of the world. I couldn’t have been more wrong. Orkney may feel isolated today, but when the Atlantic was bridged with boats instead of planes flying out of densely populated southern urban centres, Orkney was much more central.

Maps of the world on display in Orkney did not have the equator as the centre of the image. Rather, they tilted the globe northward, bringing into focus areas of the northern Atlantic which usually shrink into obscurity- including Orkney itself. By changing the angle from which I considered the globe, I was able to see connections that had never before been made clear to me. One of those connections bridged the wide watery expanse between Orkney and western Canada.

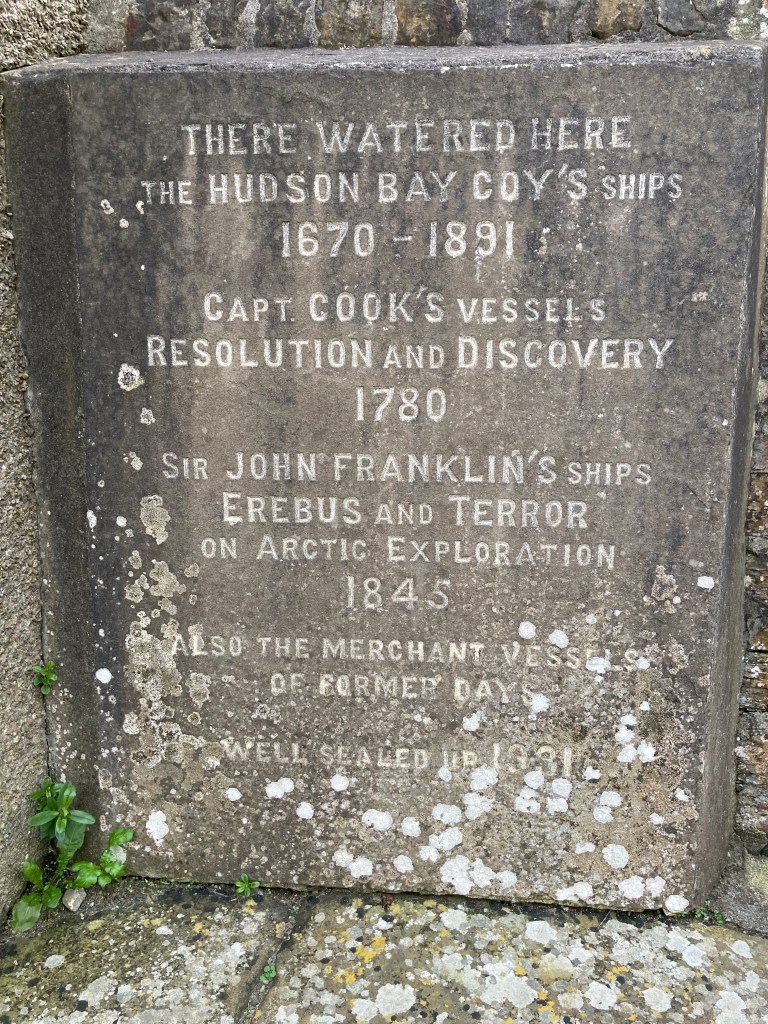

Orkney’s northerly latitude made it a geographically convenient place for the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). The oceanic entrance to the Hudson Bay is substantially further north than the mouth of the St. Lawrence seaway, which means that starting the journey from Orkney makes far more sense than leaving from a “more central” port in southern England. Hudson Bay-bound ships “called in” (made a stop at) at the Stromness harbour on the western edge of Orkney as their last landing place before braving the Atlantic crossing. Once in this harbour, they visited Login’s Well (pronounced “Logan’s”) to fill their all-important supplies of drinking water.

But it wasn’t just Orkney’s fresh water the HBC wanted. Orkney’s men were also in high demand.

Read moreEditor’s note: The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity. The banner image above is of the Carleton University School of Architecture, Ottawa, 1970. Source: University of Calgary, Canadian Architectural Archives, Carmen and Elin Corneil fonds, CA ACU CAA F0007.

Written by: Robb Gilbert, Archivist, Canadian Architectural Archives and Dorothy Field, Heritage Survey Program Coordinator

In my work with the Alberta Heritage Survey, I’m always on the lookout for sources of reliable information about Alberta’s architectural history. One such resource that people may not generally be aware of is the Canadian Architectural Archives (CAA), which is a veritable Aladdin’s Cave full of material donated by architects from Alberta and across Canada. But just what, exactly is the CAA? Recently, I had the opportunity to ask Robb Gilbert, Archivist at the Canadian Architectural Archives, about the history, holdings and services of the CAA.

(Dorothy) Hi Robb! Can you tell me about yourself and what you do at the CAA?

(Robb) I’ve been at the CAA for five years. My role is to manage the CAA’s extensive collection, improve access to the holdings, acquire new collections and additions to existing collections, teach students about the archives, assist visiting researchers, and generally raise awareness and engagement with the archives. I previously worked at the Kamloops Museum and Archives before joining Archives and Special Collections at the University of Calgary. My educational background before becoming an archivist was in religious studies and art history. Courses in art and architectural history at Carleton University in Ottawa fueled my ongoing passion for the history of Canadian architecture.

When was the CAA established, by whom, and what was its original mission?

The CAA was established at the University of Calgary 50 years ago in 1974. The idea to start an archive originated with the Dean of the Faculty of Environmental Design (now called School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape) William T. Perks (1934-2023) who proposed an archive to Ken Glazier (1912-1989), the Chief Librarian. The archive was established and developed by Perks, as well as the professors of architecture Michael McMordie and R.D. Gillmor (1930-2019), and the rare books librarian Ernie Ingles (1948-2020). McMordie built the holdings from his connections and through outreach to architects across Canada. And Ingles and the staff in the library provided the administration and operations for the archive. The original mission was to serve as a teaching and research resource for students and researchers, to collect and preserve historical records on Canadian architecture, and to promote public education and awareness about the built environment.

Read moreWritten by: Patrick Carroll, Cultural Resource Management Advisor, Southwest NWT Field Unit, Parks Canada

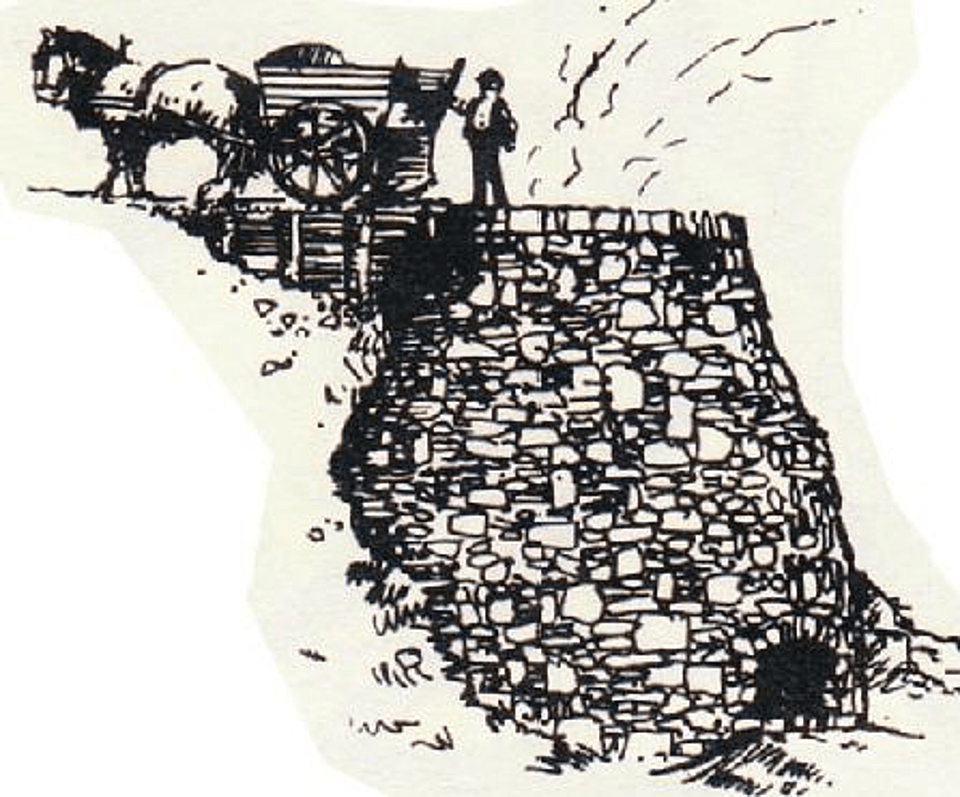

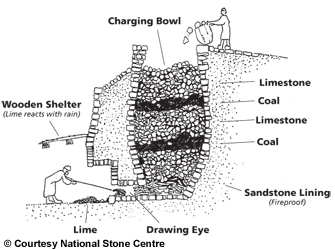

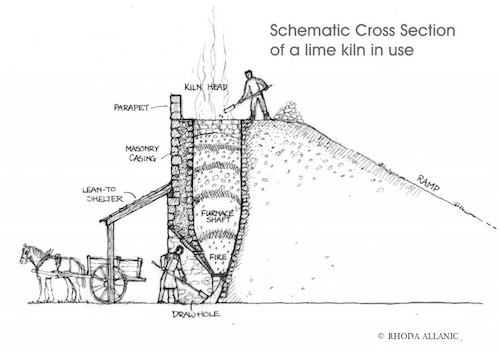

About 50 km upriver on the Slave River from Fitzgerald, Alberta, among a small cluster of islands named Stony Islands, you will find the remains of a stone lime kiln. Archaeologist Marc Stevenson documented the kiln (IjOu-5) and a nearby quarry (IjOu-6) during a survey of the Slave River in 1980. He described the kiln as a, “large semicircular limestone feature 4m in height.” The quarry is an exposed face of limestone just upriver from the kiln. All that we know about the history of the kiln is based on notes from a conversation Stevenson had with a Brother Seaurault. According to Stevenson, “The feature, according to an elderly informant, is the limestone furnace used by residents of Fort Chipewyan in the 1910’s and 1920’s to make whitewash for their log homes in the latter settlement.” It appears, therefore, to have been here for at least a century and is now showing the degradations of time, seasonal flooding and ice scouring.

The kiln is built into a natural alcove in the limestone exposure, set on a rocky shelf at a height to protect it from the impacts of seasonal high water and ice scouring on the Slave River. It consists of a semi-circular convex stone wall extending from the bedrock which, together, create the chimney. The height of the wall extends to the height of the top of the bedrock. A stoke hole on the bottom of the wall faces toward the river. An interesting feature of this kiln is that one side of the wall of the kiln does not abut directly against the limestone outcrop. The collapsing wall on the down-river side appears to have been built mostly flush to the bedrock face. The wall on the up-river side, though, remains in its original condition showing it was built with a 30-60 cm gap between the edge of the stone wall and the bedrock face. It is not known what purpose this gap might have provided for the operation of the kiln, although, it is easily wide enough to allow for a person to enter the cavity of the chimney.