Written by: Patrick Carroll, Cultural Resource Management Advisor, Southwest NWT Field Unit, Parks Canada

About 50 km upriver on the Slave River from Fitzgerald, Alberta, among a small cluster of islands named Stony Islands, you will find the remains of a stone lime kiln. Archaeologist Marc Stevenson documented the kiln (IjOu-5) and a nearby quarry (IjOu-6) during a survey of the Slave River in 1980. He described the kiln as a, “large semicircular limestone feature 4m in height.” The quarry is an exposed face of limestone just upriver from the kiln. All that we know about the history of the kiln is based on notes from a conversation Stevenson had with a Brother Seaurault. According to Stevenson, “The feature, according to an elderly informant, is the limestone furnace used by residents of Fort Chipewyan in the 1910’s and 1920’s to make whitewash for their log homes in the latter settlement.” It appears, therefore, to have been here for at least a century and is now showing the degradations of time, seasonal flooding and ice scouring.

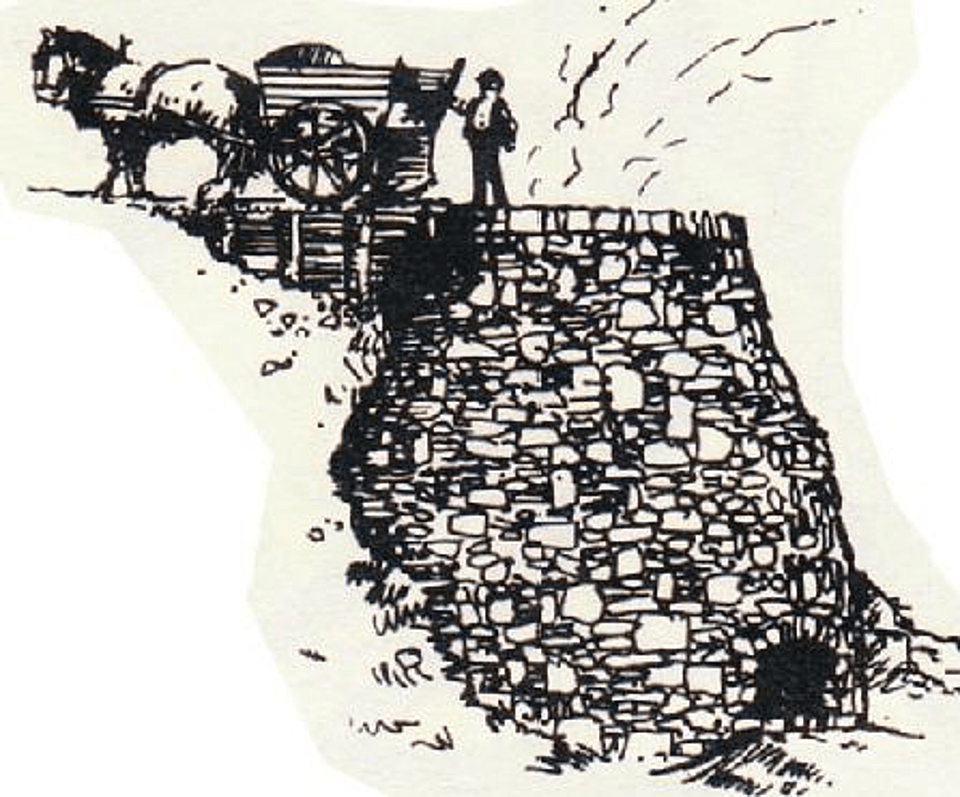

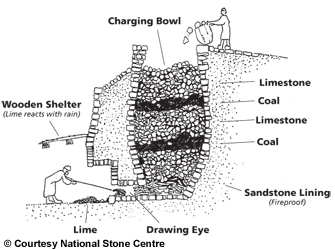

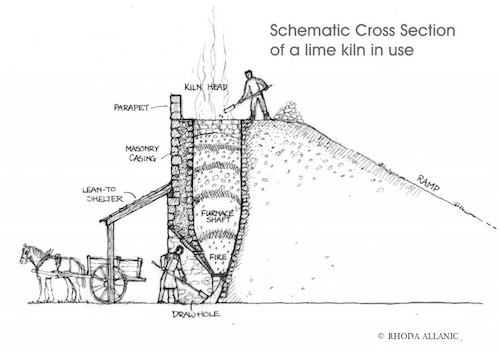

The kiln is built into a natural alcove in the limestone exposure, set on a rocky shelf at a height to protect it from the impacts of seasonal high water and ice scouring on the Slave River. It consists of a semi-circular convex stone wall extending from the bedrock which, together, create the chimney. The height of the wall extends to the height of the top of the bedrock. A stoke hole on the bottom of the wall faces toward the river. An interesting feature of this kiln is that one side of the wall of the kiln does not abut directly against the limestone outcrop. The collapsing wall on the down-river side appears to have been built mostly flush to the bedrock face. The wall on the up-river side, though, remains in its original condition showing it was built with a 30-60 cm gap between the edge of the stone wall and the bedrock face. It is not known what purpose this gap might have provided for the operation of the kiln, although, it is easily wide enough to allow for a person to enter the cavity of the chimney.

Making Lime

Lillian Klassen’s family homesteaded near Rosthern, Saskatchewan in 1899. In her handwritten memoir she describes the operation of a kiln that was built near her home. Her father had purchased the kiln to operate as a business. He hired local men to assist with the operations:

They were anxious to get some work to get a little needed cash so my father hired several as there was a lot of work. At first several men with a team had to drive along the riverbank and break up the lime stones with a crowbar which were plentiful along the bank and haul them to the lime kiln. Others had to chop down the dry trees and haul them to the site and cut them in cord wood lengths for firewood as one man had to sit and replenish the fire as it had to be kept burning for 3 days and nights. The lime was ready when a blue flame showed on top of the lime. To start with my father had to build a kind of fire box for the fire. After that was done the stones were just dumped in. Before any lime could be removed it had to cool off for a couple of days. Then my father had to crawl in with a crowbar and dislodge the key stone as the lime could tumble down as it had to be taken out below. My parents hauled a lot of lime to Rosthern for foundations and plastering the first large buildings as the public school and the Queen’s Hotel. Farmers would come along from far around getting loads of lime when they were building to make foundations & plaster as there was no cement in use at that time. The lime weighed 60lbs to the bushel as that was the way it was sold. It was measured in a bushel box at the lime kiln. My grandfather knew how to prepare the lime for use. So, he slaked lime and made the foundation for our house which was built in 1900. A young man John Baerg helped build the house and later also plastered it.

Lime: Quicklime, Whitewash, and Other Uses

Lime is produced by high temperature, controlled firing of limestone. Burnt limestone (calcium oxide) is called quicklime or burnt lime. Quicklime is chemically unstable until it is mixed with water, or hydrated, in a process called slaking. Water mixed with quicklime (calcium oxide) causes a chemical reaction characterized by extreme heat during which the calcium oxide is transformed to calcium hydroxide, or hydrated lime. Quicklime (unhydrated) and slaked (hydrated) lime are used in modern agricultural, industrial, and commercial industries. In early twentieth century Fort Chipewyan, lime could have been used for a variety of domestic purposes, including whitewash.

To make whitewash, hydrated lime is mixed with water. The resulting mixture was used for coating the exterior and interior surfaces of buildings. Applied like paint, it creates an impermeable surface, making exterior walls waterproof. It is also flexible enough to account for shifts in wood or rock structures due to changes of temperature and of season. As the name tells us, whitewash would brighten the interior of buildings. Because it is made from lime (calcium hydroxide), whitewash used on the interior of a house will also aid in repelling insects. Lime can also be used to reduce the smell and to increase the rate of decomposition in outhouses. Another important use for hydrated lime is in producing mortar and plasters that could also be applied to the interior and exterior surfaces of buildings. Since ancient times, lime has been used agriculturally to reduce the naturally occurring acidity of soils.

As well as the whitewash mentioned by Brother Seaurault, lime produced at the kiln on the Slave River could have been: used to improve the soils in community gardens; used in outhouses, stables and dog yards; used in the tanning of hides; potentially used for medicinal purposes; used in the making of plasters and mortars to be applied to walls, floors, and ceilings; and used as chinking in log buildings.

What Little We Know

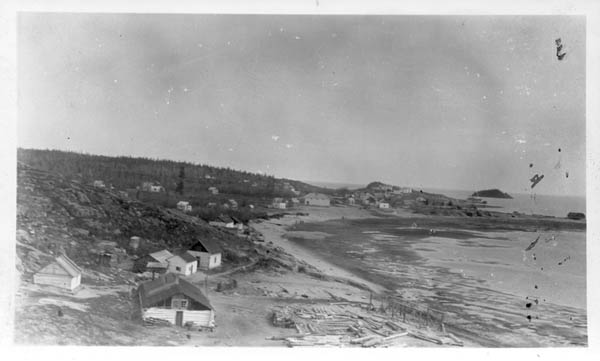

We know frustratingly little about the Stony Islands Kiln except that it closely resembles kilns commonly found on homestead sites in western Canada and across the British Isles and Europe where many of the settlers originated. Architecturally, it falls within a broad European vernacular tradition. Located on the frontier of settlement in the early twentieth century, does the kiln represent the northernmost expansion of these early pioneer technologies and traditions?

No evidence of the lime making operations remain in the landscape: tree stumps or logs, remains of a camp, slaking pools, worn trails between the limestone quarry and the top of the kiln, stockpiled limestone; none were documented during prior visits to the site. The only known artifacts associated with the kiln and quarry were a pail and a crowbar, both of which are gone. Aerial photos dating to the 1930s and 1940s do not show any clearing on the island, nor on nearby islands or the mainland, therefore providing no indication of the amount of wood that was cut to supply the operations. The kiln and the quarry are part of a cultural landscape that has been muted.

We are left with only the kiln; a semi-circular wall composed of pieces of limestone with a mud mortar, built against a limestone outcrop. Sometime after 2006, the wall started to collapse. The history of the kiln, as soon will be the kiln itself, is succumbing to the currents of time.

Sources

Johnson, David J. 2018 Lime Kilns: History and Heritage. Amberley Publishing, Great Britain.

Klassen, Lillian. n.d. My Pioneer Days in Saskatchewan. Unpublished manuscript. Saskatchewan Archives: Regina.

Stevenson, Marc. 1981 Archaeological Survey of Rivers Adjacent to the Eastern Boundary of Wood Buffalo National Park. Final Report, Permit No. 80-130. Parks Canada.