Written by: David Murray, Architect AAA, FRAIC

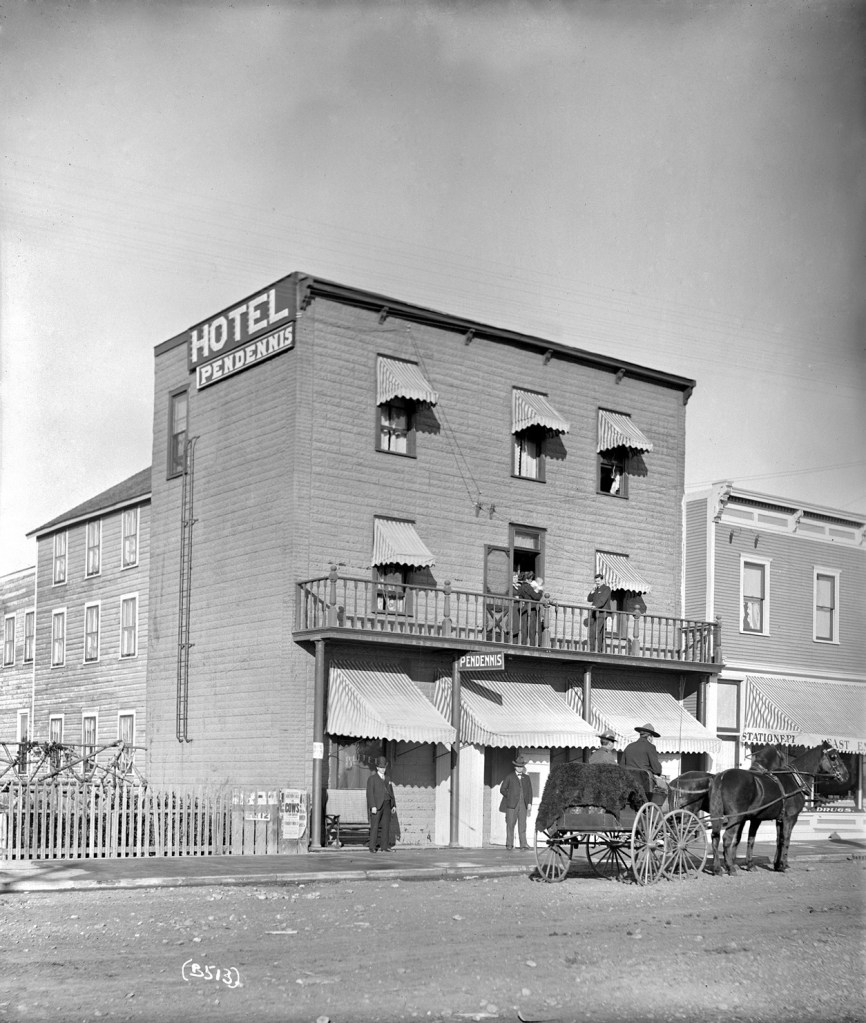

This story begins with the discovery of hundreds of artifacts that were uncovered during the dismantling of the interior of the original Pendennis Hotel in Edmonton in 2006. The Pendennis Hotel, located at 9660 Jasper Avenue, dates to the late 1890s when it was formerly named the California Rooming House. The earliest photo of the building is dated 1898.

In 1911, owner and proprietor Nathan Bell doubled the size of the hotel when he purchased the lot next door to the east, demolished the drug store building and constructed the enlarged hotel. The expansion incorporated, intact, the original Pendennis behind a new brick façade designed by Lang and Major Architects from Calgary.

In 2006, architects David Murray and Allan Partridge were engaged to conduct a feasibility study for the conversion of the 1911 Pendennis Hotel to a building that would provide a new home for the Ukrainian Canadian Archives and Museum of Alberta (UCAMA). The initial study included assessing the condition of the former hotel and documenting its configuration. It was at this time that we discovered the original pre-1911 building that had been simply retained and incorporated behind the new brick facade.

In 2006, the building we started working on was then known as the Lodge Hotel, a contemporary Jasper Avenue rooming house. The building had been previously designated as a Municipal Historic Resource during the earlier Jasper East Village Main Street Project in 2001, along with its neighbour, the Ernest Brown Block. Both had been purchased by UCAMA.

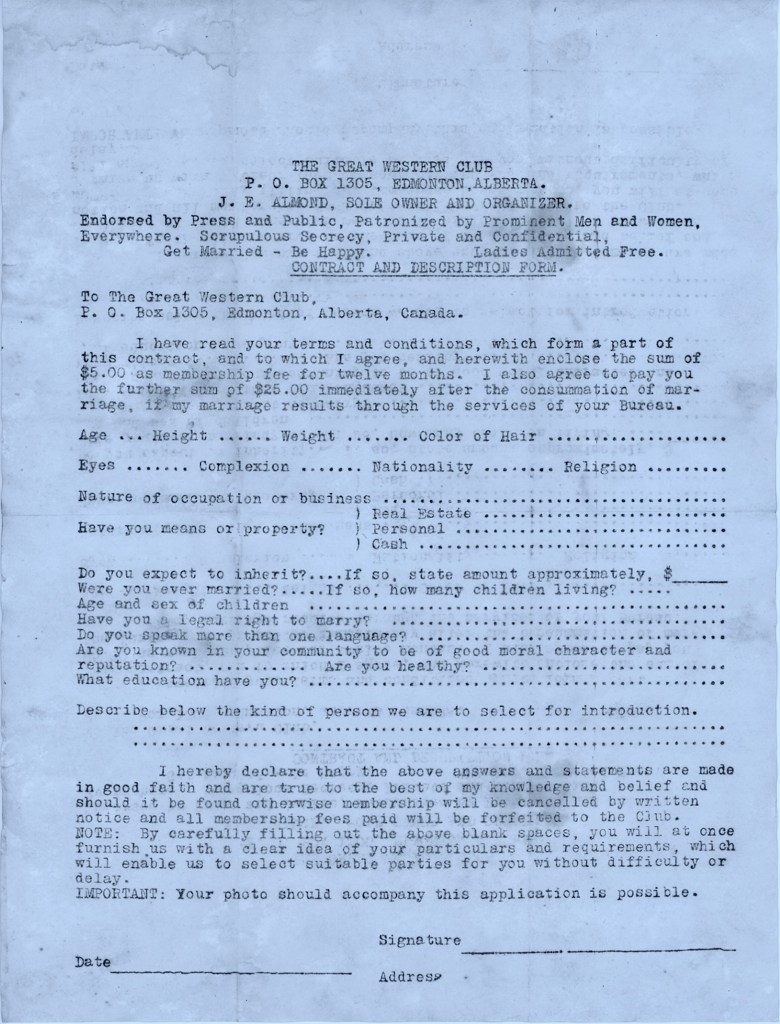

With completion of the feasibility study in 2006, construction of the new home for UCAMA began the following year. It was during the interior dismantling that hundreds of hidden artifacts were uncovered. They tell somewhat mysterious stories of life in the hotel and its subsequent rooming house uses after 1920. The artifacts included historic maps, kitchen equipment, a traveller’s account book from a dairy in San Francisco, many emptied bottles of Jamaica Ginger (an alcohol-based ‘medicinal’ tonic that presumably was a substitute for alcohol during prohibition 1916-1923) cards, letters, medicines and clothing. Among the artifacts was this application to The Great Western Club, a matrimonial agency owned by J.E. Almond. This application was probably left behind by an inhabitant of the hotel.

With the proliferation of dating sites online these days, I was interested to find out more about J.E. Almond and his motivation to start a matrimonial agency in the era of World War 1. The earliest newspaper reference to J.E. Almond and the Great Western Club in western Canada that I was able to find, is from 1917 in the Edmonton Journal. It is reported in Police Court News that J.E. Almond, was a member of the Woods Locating Company (a detective agency?), where he is charged with, “obtaining the sum of $20 by false pretenses with intent to defraud George H. Webb.” Almond was remanded to higher court for trial.

In September 1917, it is reported in the Edmonton Bulletin Supreme Court Docket that a case of, “false pretenses” against J. E. Almond was set for trial. There are no details of this case.

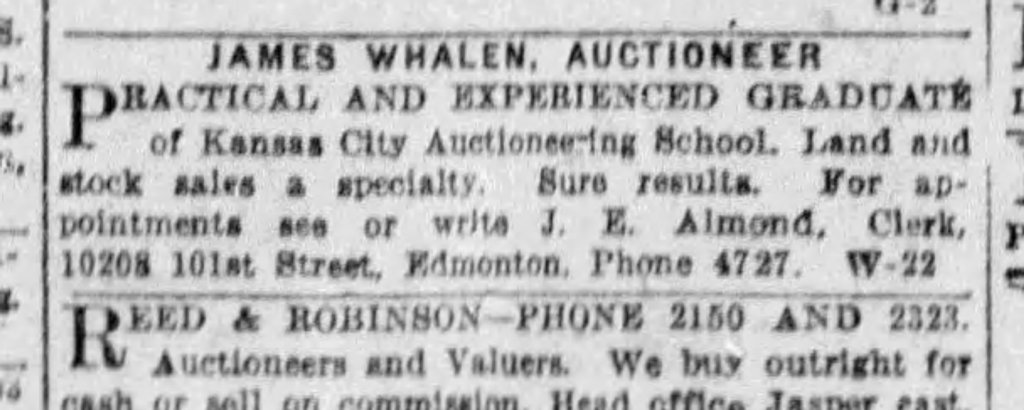

In March 1918, it was advertised that J.E. Almond was a clerk for James Whalen, auctioneer.

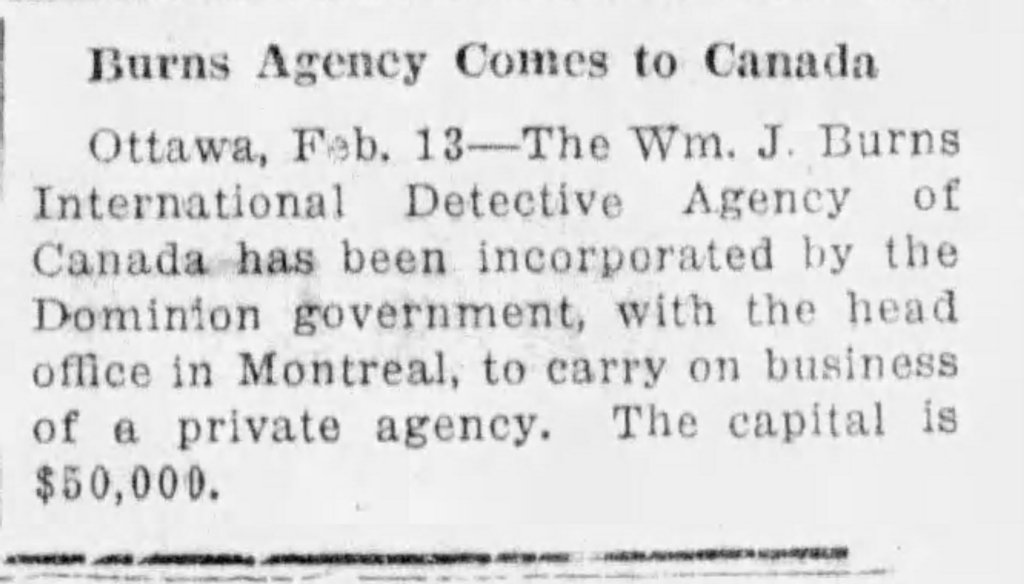

In 1919, J.E. Almond announces that he, as Principal, has opened an Edmonton branch of the International Detective Agency. Almond states in his July 1919 advertisement that, “our Quality of Service…is the best attainable in America”. This international reference suggests that Almond was seeking to associate his venture with the famous William J. Burns International Detective Agency established in 1909 in the USA. We don’t know if Almond’s detective business was a legitimate association with the Canadian organization headquartered in Montreal. Almond continued to advertise his International Detective Agency into the 1920s.

The Great Western Club: A hymeneal organization

“Get Married – Be Happy….Ladies Admitted Free”. The cost of joining the club was $5 for the men. The club, presumably J.E. Almond himself, would be the match-maker. Members would agree to an additional $25 fee immediately after the consummation of the marriage. We are left to wonder how the details of the club contract would be managed and how privacy, secrecy and confidentiality could be ensured.

A search for the Great Western Club did not result in an announcement of its origins. The first Edmonton Journal reference is about a lawsuit initiated by Mrs. Nora Calder against J.E. Almond as published on June 8, 1918 in the Edmonton Journal. She claimed that The Great Western Club, despite its claims for scrupulous secrecy, published her name as one who desired a third husband and that she was, “molested and insulted by strange men.” She sued for $2,500 in damages. “Mrs. Calder claims that she is a married woman living with her parents in Edmonton and that in February of this year, Almond wrongly and falsely published her in the lists…In counterclaim, the defendant states that Mrs. Calder during March made false, malicious and slanderous statements about his bureau and injured his business to the extent of $5,000, which he claims as damages.” I was not able to find any follow-up of any the court settlements and claims against J.E. Almond.

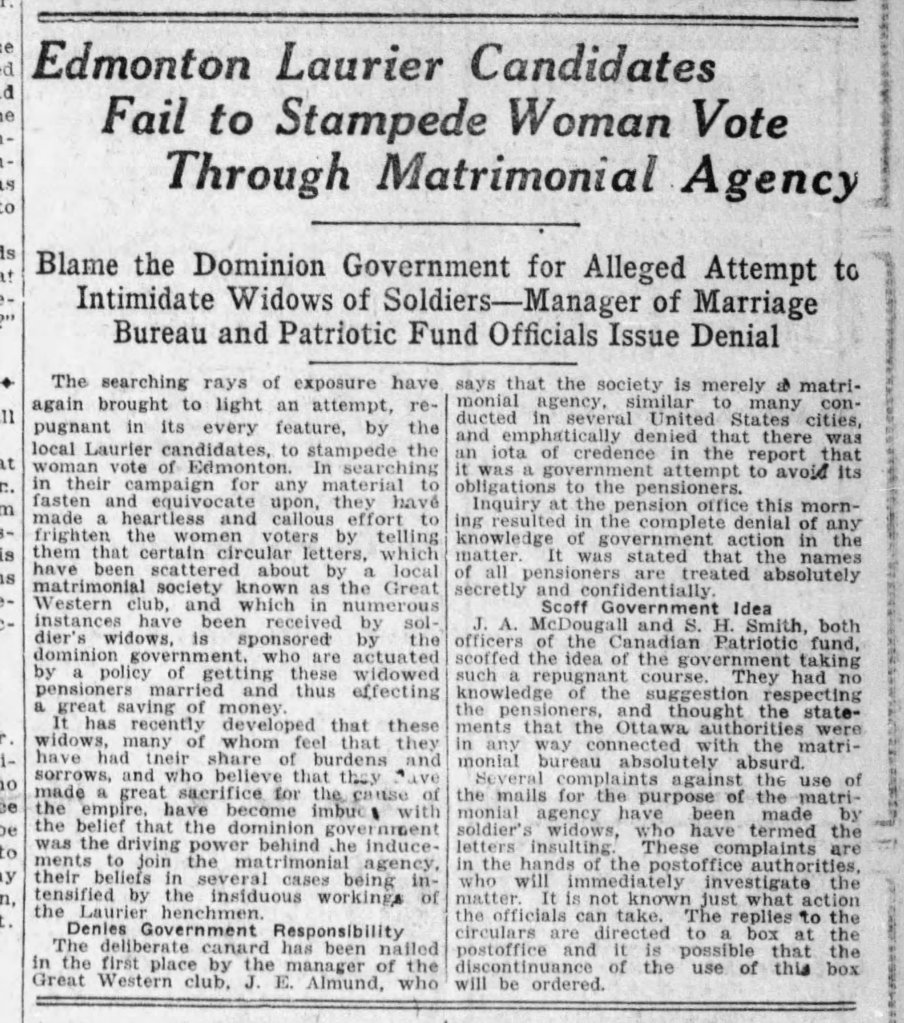

The story of the Great Western Club becomes even more intriguing when the Edmonton Journal reported on December 15, 1917 (the federal election was held that year 2 days later on December 17) an allegation by the local Laurier candidates (Liberal opposition in the federal government at the time was led by Wilfred Laurier) that the Dominion government under the leadership of Conservative Prime Minister Robert Borden, through The Great Western Club, were circulating letters to widows of WW1 soldier victims to get these widowed pensioners married and off the government payroll.

J.E. Almond denied any government responsibility, although it is reported that many soldiers’ widows received the matrimonial agency letters. The Ottawa pension office stated that, “the names of all pensioners are treated absolutely secretly and confidentially. Several complaints against the use of the mails for the purpose of the matrimonial agency have been made by soldiers’ widows who have termed the letters insulting.” The post office was given the task to investigate the complaints. It is suggested in the article that the post office box in the circulars might be discontinued, which could be ordered by the post office. I was not able to find any further reference in my newspaper research but given the background of J.E. Almond, as reported several times in the Edmonton Journal, perhaps The Great Western Club was short lived.

The last reference to J.E. Almond in the Edmonton Bulletin was the 1924 announcement of the funeral of his wife May Almond. It is stated that the couple lived in Waskatenau at the time, a village 90 km NE of Edmonton. May was buried in the Edmonton Cemetery, and therefore I would not be surprised if J.E. Almond was also buried there. Unfortunately we were not able to locate a reference to either of the Almonds in the Edmonton Cemetery database and I was not able to locate an obituary for J.E. Almond.

The Pendennis and prohibion

The Great Western Club existed at a time during the height of the Pendennis Hotel. The imposition of Prohibition in 1916 was the death knell for many hotels in Alberta who relied on their liquor sales. Nathan Bell lost his hotel in 1919 which was put up for judicial sale by the City as reported in the Edmonton Bulletin on December 6. There are many more stories embedded in the artifacts we found in the 2007 building renovations. The WW1 period of Prohibition remains one of those periods and this packaging reminds us of the continuous occupation of one of the oldest remaining hotel buildings in the city.

This item, found in the Pendennis Hotel, was packaging for Jamaica Ginger extract, prepared in Edmonton by the Wm. Haynes Pharmacy on Jasper Avenue. It was a late 19th-century patent medicine that provided a convenient way to obtain alcohol during the era of Prohibition, since it contained approximately 70 to 80 per cent ethanol by weight.

Fascinating, David! Thank you.