Written by: David Monteyne, Professor, School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, University of Calgary

Between 1885 and 1930, the Dominion government built and operated about a dozen immigration halls in Alberta (and rented space for this purpose in a dozen more towns), from Lethbridge and Medicine Hat in the south to Grande Prairie and Peace River in the north. But what, exactly was an “immigration hall”?

An immigration hall was a place where the federal immigration branch provided free accommodations as well as advice to new arrivals from Europe, the United States and even eastern Canada. These prairie immigration halls were part of a nationwide building program, described in my recent book, for which the federal Department of Public Works designed and built: pier buildings in ports like Quebec City and Halifax (Pier 21, now the Canadian Museum of Immigration); immigrant detention hospitals; and quarantine stations on both coasts. Of all of these, the immigration halls were the most numerically significant, with more than 50 buildings erected across the three prairie provinces. The immigration hall was a newly invented building type, unique to Canada.

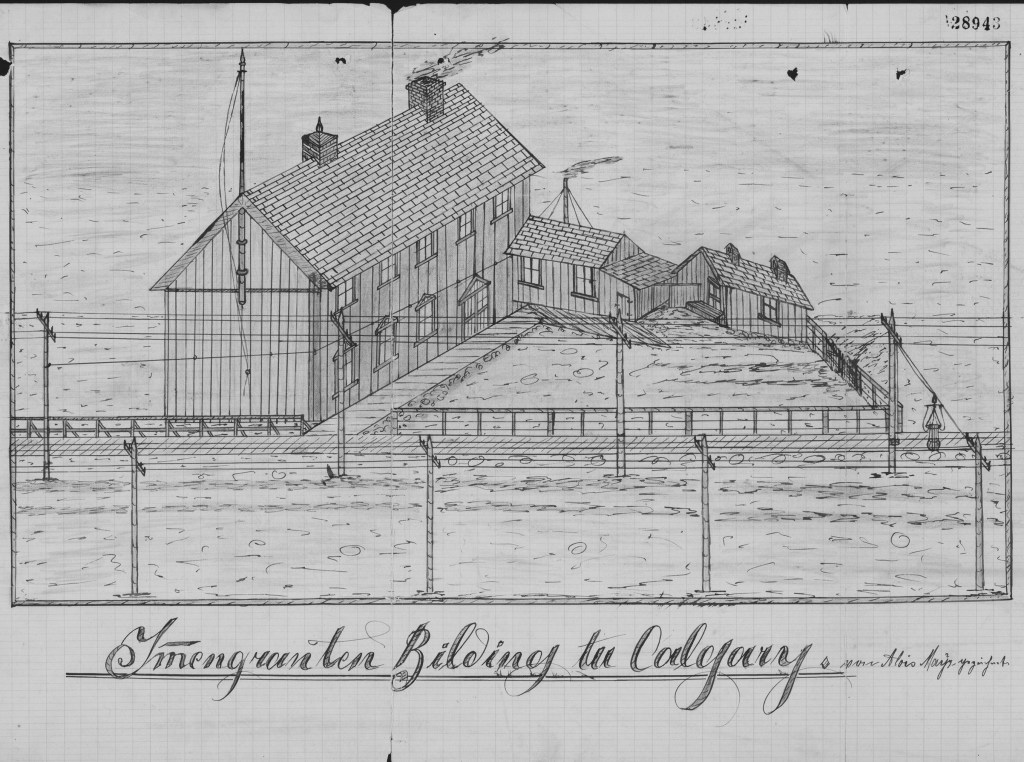

Calgary’s 1885 immigration hall was the first in Alberta, and among the first few built anywhere. As we see in this 1896 sketch gifted to the immigration agent by a grateful immigrant who stayed there, the Calgary hall was a two-storey, five-bay wide, wood-frame structure with board-and-batten siding. The ground floor was one large common room with rough tables and chairs and a cookstove for use by the immigrants. Upstairs were two large dormitories with built-in bunks (i.e., simple wood platforms). It was originally intended that the dormitories be sex-segregated, but this proved impracticable. Later, the upstairs floor in Calgary (as elsewhere) was divided into smaller rooms more suitable to lodge families in addition to single men. In the Calgary yard were three outbuildings, a caretaker’s cottage, the agent’s office and the biffies. Though the structure was centrally located across the tracks from the CPR station and eventually the opulent Palliser Hotel, the government deigned to pay for sewer connections until the City of Calgary actually condemned the immigration hall after a typhoid epidemic in 1912.

As the first, and sometimes the only, Dominion government building in a prairie town, the immigration halls were often called upon to serve other uses as well. Calgary’s immigration halls incorporated the federal courthouse in the late 1880s, and briefly became a relief shelter during the 1893 recession. The immigration halls in Edmonton served the same emergency purpose in the first years of the Great Depression. At other times, more remote immigration halls were accommodation for census takers or military recruiters. With their relatively large interior spaces, they also hosted local cultural events like dances, weddings and religious services, as in the immigration hall at Medicine Hat.

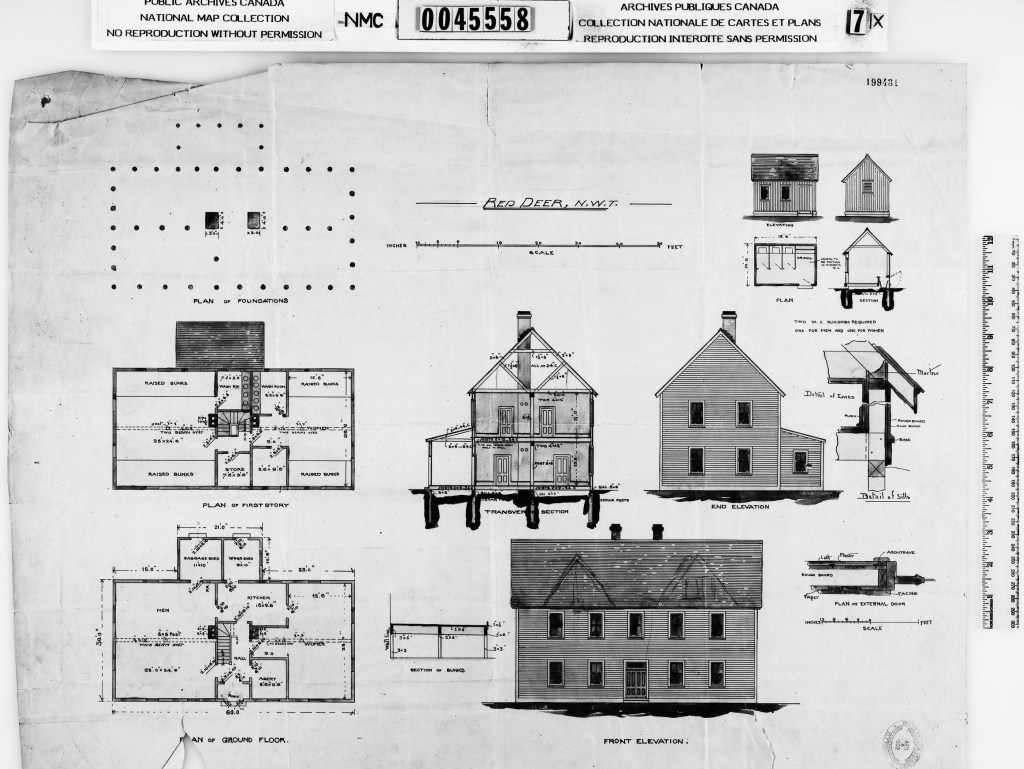

The scale of the Calgary building became standard for immigration halls built up until 1908, though the plans became more sophisticated as early as the 1890s. As we see in the full Department of Public Works drawing package for the (unbuilt) Red Deer immigration hall, changes include the central entrance that provides symmetry and order to both the plan and the elevation. The plans are now more thought-through, with a central chimney core around which radiate the agent’s office, kitchen and segregated common rooms; upstairs are a combination of dorms and family rooms. In 1904, Edmonton and Medicine Hat received more fancy versions of this design, with the symmetry of the façade emphasized by a raised entrance, classical pediment and flanking dormers and decorative finials. These fancier halls also included a basement with deep bathtubs, laundry facilities and a furnace for central heating.

After 1908, the standard design changed again, as seen in the postcard of the Edson immigration hall, which is no longer symmetrical or dignified with decoration. Now a one-storey building, the new halls were divided into functional areas, with the caretaker’s apartment and guests’ common rooms to the left of the entrance, and a wing of family rooms down a double-loaded corridor to the right. In a pinch, the externally-accessed attic could be used as a dormitory. One-third of the Peace River immigration hall, built in 1917 to this later design, survives as a private residence; the original immigration hall there was subdivided into three structures after Public Works sold it off in 1937.

Other than this Peace River residence, the only Alberta immigration hall that survives today is the substantial Edmonton hall, built of concrete and masonry at the end of the 1920s to replace several earlier halls in that city. This new structure marked both the modernization of the Prairie immigration hall as an institutional building type, and also its culmination. During the Great Depression and the Second World War, the flow of immigrants dried up and, along with it, the need for the Dominion Government’s immigrant reception architecture.

In my book, I propose that the prairie immigration halls were proto-social welfare institutions. In the context of the larger building program, immigrants were to be guided, aided, advised, sheltered and protected from the time of debarking into a Dominion Government pier building until they found work or a homestead on the prairies. In the late 19th century, the government increasingly – though reluctantly and somewhat selectively – recognized that it held some responsibility for the wellbeing of people within Canada, especially immigrants that it had convinced to come here with its promotional campaigns.

Although it is a work of architectural history, the immigrants’ experiences, stories and voices are foregrounded in the book, drawing on memoirs, recorded oral histories, newspaper accounts and historic photos. For these sources, I drew on both digitized and analog collections across the prairie provinces. In Alberta, I found rich material remembering immigrant experiences in the collections of the University of Calgary Library, Provincial Archives of Alberta, Glenbow Archives, South Peace Regional Archives, Athabasca Archives, the Esplanade Archives in Medicine Hat and in Peel’s Prairie Provinces at the University of Alberta.

A superb piece. Thank you. Ian CSent from Ian’s iPhone