Editor’s note: Learn more about the history and heritage of Black Albertans from the Royal Alberta Museum.

Written by: Michael Gourlie, Government Records Archivist, Provincial Archives of Alberta

Since the 1960s, the Provincial Archives of Alberta (PAA) has acquired kilometres of records, millions of photographs and thousands of hours of audiovisual recordings about the lives and activities of Albertans. While Alberta’s Black community is underrepresented among these archival holdings, it faces a similar challenge to other groups. For every famous individual whose life is documented in detail in numerous sources, there are dozens of other individuals who remain nameless and forgotten until someone researches their stories.

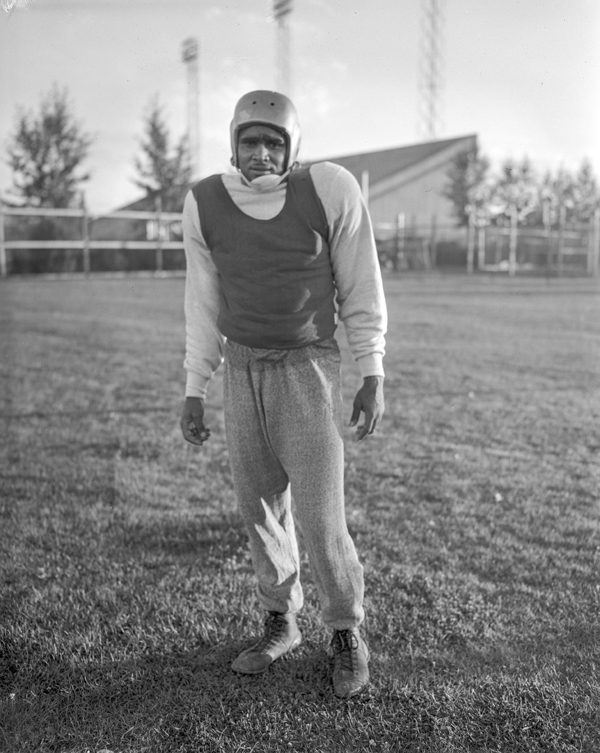

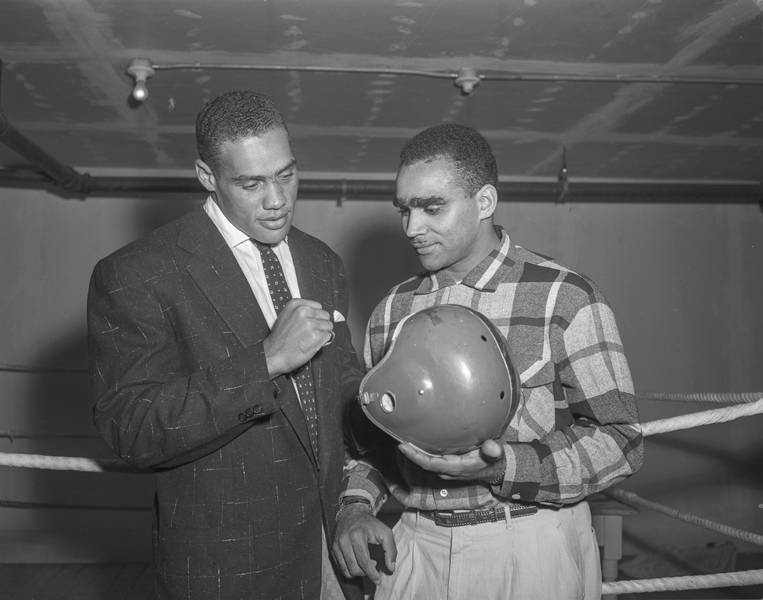

Among the famous individuals found in the PAA’s holdings is John Dee (Johnny) Bright. Born in Indiana in 1930, he attended Drake University on a track and field scholarship, which led to a remarkable collegiate football career marked by several National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) records as well as a national profile. His senior year in 1951 was also notable when he was the target of a racially motivated assault on the playing field during a game with Oklahoma A&M University (now Oklahoma State University), an incident documented in a Pulitzer Prize winning series of photographs. While some on-field rules changed because of the incident, the opposing team and its university administration denied any wrongdoing for decades and only apologized for the incident in 2005.

He graduated from Drake University in 1952 with a Bachelor of Science in Education, specializing in physical education. He was the first pick chosen by the Philadelphia Eagles in the 1952 draft, but fearing his treatment in the National Football League, he chose to emigrate to Canada and play for the Calgary Stampeders. He was traded to Edmonton in 1954, where he primarily played offense. Bright set several Canadian Football League (CFL) records, helped the team win the Grey Cup in 1954, 1955 and 1956, and was named Edmonton Athlete of the Year in 1959.

After retiring from football, he became a teacher and football coach in the Edmonton public school system, ultimately becoming the principal of D.S. Mackenzie Junior High School and Hillcrest Junior High School. He died suddenly in Edmonton in 1983 during a surgical procedure to address a long-standing knee injury from his football career. He is commemorated by his inclusion in the Canadian Football Hall of Fame, the Johnny Bright School within the Edmonton public school system, and the John Dee Bright College, a two-year college at Drake University.

While written and photographic sources about the life and career Johnny Bright are readily available, there are thousands of photographs featuring unidentified people whose backgrounds are difficult if not impossible to discover. This lack of identification is particularly noticeable in the portrait photography in the Ernest Brown records. Known primarily for his early cityscapes and landscapes in Western Canada, Brown and his partner Gladys Reeves also took portrait photographs of everyday Albertans who commissioned them. While the portraits capture a unique cross-section of Albertans, the business records of Brown’s studio are incomplete or missing altogether, so identification of individuals in photographs or determination of the date of the image is difficult to pinpoint. Some Brown images are relatively well-known figures in Alberta history, such as Father Albert Lacombe or Premier Alexander C. Rutherford, but many photographs have very limited information to identify the sitter.

This portrait of an unidentified Black woman is typical of the images found among Brown’s portrait work. Featured in a previous Black history month post, there are few clues as to this individual’s identity except for the notes at the top of the negative, which read “15552 Sneed 6 P.C. B&W.” These administrative details used to track the negative provide the single clue, the name Sneed, that ties this photograph to a woman connected to the earliest Black families to settle in Alberta.

According to data from the 1916 Canadian census (a date which seems to align with the style of clothing), there were several women with the last name Sneed living in Edmonton at the time this photo was taken. One possibility for the woman in the photograph is Elizabeth Jefferson Sneed (1881-1918). She was the wife of Henry Sneed, the man who ventured from Oklahoma to Alberta in 1905 to assess the suitability of the land for Black settlers. Along with several other families, Henry and Elizabeth came to Alberta in July 1910 and settled in what is now Amber Valley. Their two daughters would have been too young to be the woman in the photograph.

But there were at least two additional women with the last name Sneed living in Alberta in 1916 who could be a possibility. Pearl Risby Sneed (1895-1964) was living in Edmonton in 1916, and she would have been in her early twenties. As with Elizabeth Sneed, her female relatives would have been too young to be the woman in the photograph. Anna Sneed (1895-1918) also lived in Edmonton and worked as a housekeeper; she and her husband had no children.

There is also the possibility that a Sneed family member paid for the photographs, but they depict someone from outside the family. Without dated and identified photographs to act as reference point, a researcher currently can only speculate about the sitter’s identity. Further research, future donations of records, or the rediscovery of Brown’s studio records might uncover the necessary clues to confirm who sat for the portrait.

That’s the joy and frustration of archival research into communities that are underrepresented in the holdings of the PAA. The records preserved by the PAA likely include evidence of someone who had a broader impact in Alberta history, but they may or may not capture a fragment of the life of an everyday Albertan. Who knows? In the case of an anonymous photograph, a fortunate researcher soon might uncover that bit of evidence that, for just a moment, turns someone forgotten into someone famous.