Editor’s note: The banner image above is courtesy of the Royal Alberta Museum.

Written by: Devon Owen Moar

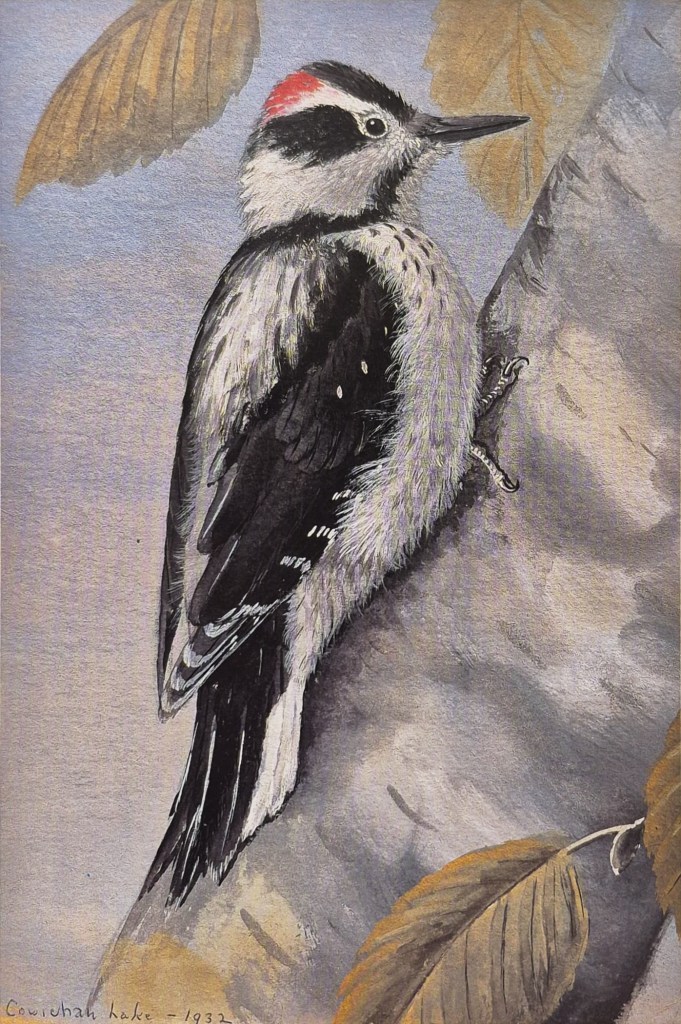

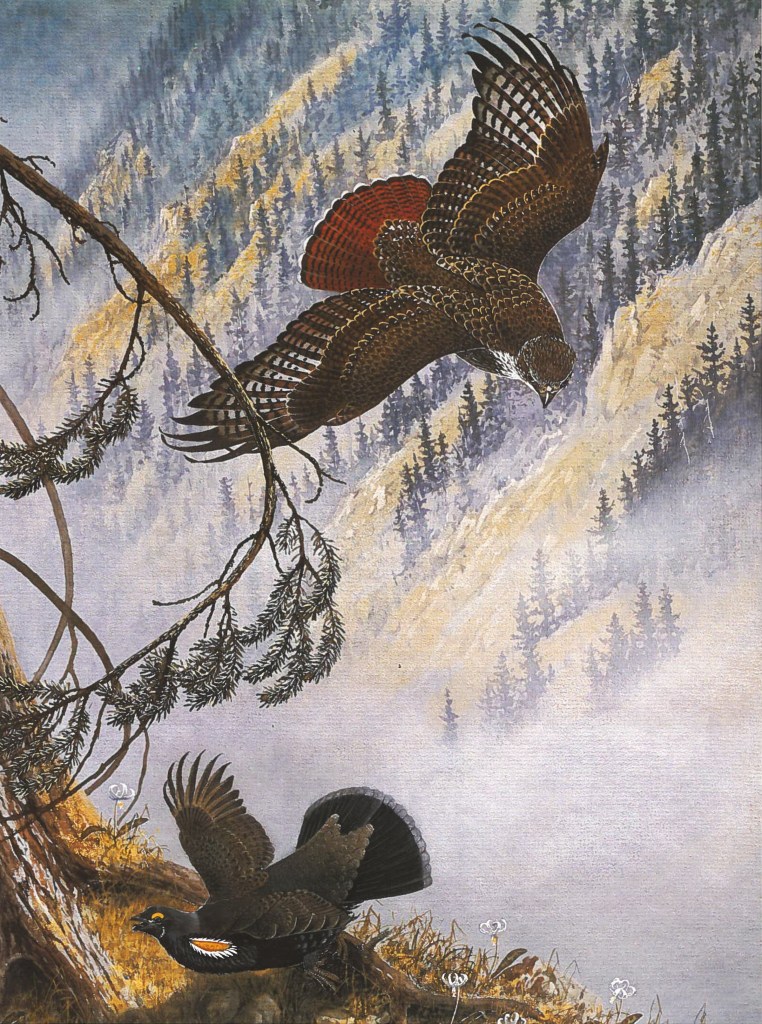

At first glance, the illustration appears simple: a bird, carefully rendered, set within its landscape. There is no dramatic gesture or overt narrative—there is only close attention. Feather by feather, stroke by stroke, the image invites the viewer to slow down and really look. It is both an artwork and a record, capturing not just the likeness of its subject, but a way of seeing that is central to the natural sciences and natural history museums.

This work, now part of the Royal Alberta Museum’s collection, was created by Frank L. Beebe, a self-taught naturalist, illustrator and falconer whose career bridged art and science. Beebe’s illustrations were never meant to be decorative alone; they were tools for understanding, shaped by careful observation and extensive field experience.

Before photography became the dominant way of documenting the natural world, scientific illustrators played a vital role in how knowledge was recorded and shared. People like Beebe translated hours of study into images that could educate, inform and endure. This kind of work helped shape how museums studied and presented the natural world.

This single illustration offers a point of entry into Beebe’s broader world, rooted in western Canadian landscapes and museum and illustrative practices, and reminds us of the important, and often unsung, role illustrators play in connecting science, art and public understanding.

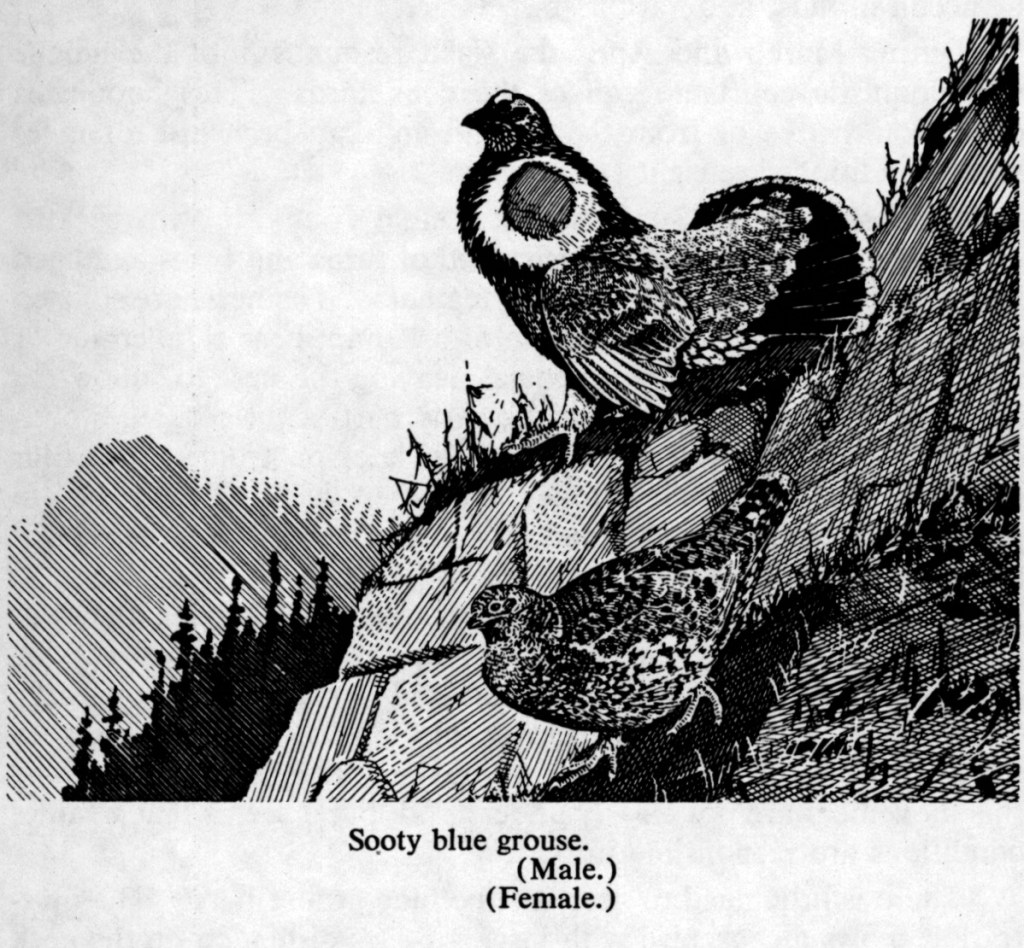

The work that prompted this research is a framed painting depicting a male Sooty Grouse. It is signed in the bottom right corner by the artist, Frank L. Beebe. The grouse is shown mid-display, its body fully puffed with its yellow throat air sacs inflated and tail held upright—a striking posture associated with courtship. Beebe situates the bird within a carefully rendered landscape: a moss-covered rock forms the backdrop, while long grasses, white and yellow flowers (likely avalanche lilies) and a fallen leaf help situate the foreground.

The painting appears to have been executed using watercolour for the surrounding landscape and, most likely, opaque watercolour to model the grouse itself. It is mounted with a tan mat in a simple stained wooden frame. A label for Kensington Fine Art Gallery Ltd., located in Calgary, is visible on the back, suggesting that the work circulated through this gallery at some point.

It is unclear whether the image was produced as a standalone artwork or for use as an illustration in a publication. Now preserved within the museum’s collection, the painting offers both a vivid image of a species native to western Canada and an entry point into Beebe’s wide-ranging career as an illustrator, naturalist and museum worker.

The subject of this painting, the male Sooty Grouse, is one of the species Beebe illustrated in his earlier work for the British Columbia Provincial Museum. The museum’s Handbook No. 10: Birds of British Columbia (Upland Game Birds), written by the museum’s ornithologist, C.J. Guiguet and illustrated by Frank Beebe, notes that, “blue grouse have been a subject of controversy for many years among those interested in the speciation of birds, for two different-appearing groups are present in western North America. In British Columbia we have both groups, and some workers claim that each should have full specific status.”

In the past, and until fairly recently, the two birds were considered a single species: the coastal Sooty and interior Dusky Grouses were both referred to as the Blue Grouse – “a blue grouse is a blue grouse wherever encountered.” However, they differ in voice, plumage and behavior. This handbook on upland game birds presents Sooty and Dusky under their own sections to highlight these differences. These game birds are related to the common barnyard chicken: “they have short, rounded wings and spend most of their time on the ground; they are excellent runners, very seldom make prolonged flights, and even the highly coloured ones are adept at hiding.”

The handbook describes the males’ inflated air-sacs as, “highly specialized in the mating season, thick, gelatinous, the surface deeply corrugated into a series of tubercles of velvety texture and of a deep yellow colour,” while the mottled grey and brown female is shown below for comparison. This careful attention to detail, combined with field observation and artistic skill, exemplifies Beebe’s approach to natural illustration, bridging science and art in a way that brings the Sooty Grouse vividly to life for both specialists and the general public.

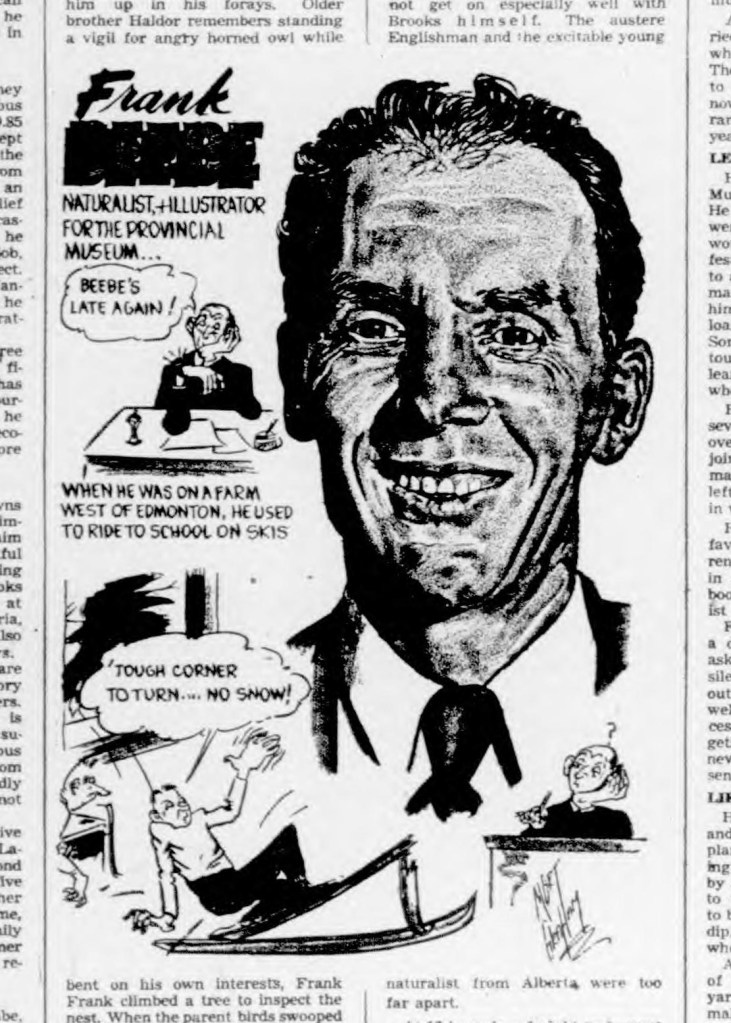

The second youngest of seven children, Francis Lyman Beebe was born on May 25, 1914 in Lacombe, Alberta. From a young age, he displayed an insatiable curiosity about the natural world. After the family moved to a farm west of Edmonton, in the wild muskeg country near Peers, Beebe spent much of his childhood exploring forests, hunting and observing birds, and raising owls and hawks. Reflecting later on those years, he recalled: “‘I raided owls’ nests and hawks’ nests: raised young hawks, hunted rabbits, and hunted squirrels professionally.”

One particularly telling story from his youth describes Beebe raising a Great Horned Owl to adulthood and training it to return at his call, startling unsuspecting passersby as it swooped from above. He also kept a pygmy owl as a companion, carrying it with him to and from school. These early, hands-on encounters with wildlife shaped both his confidence and his way of seeing animals—not as distant specimens, but as living beings to be closely observed, understood and respected.

Beebe’s childhood was marked by independence and self-sufficiency, skills honed during long winters traveling to school on skis and exploring the boreal forests that would shape his lifelong connection to nature. By his teens, he was already producing illustrations of the animals he studied, using real-life “study skins” to capture their form with accuracy. His talent was largely self-taught; he never took formal lessons in art or zoology, yet by adulthood he was considered one of Canada’s foremost wildlife illustrators. “‘I was one of those men who didn’t have to pick their vocation,’ Beebe later recalled. ‘It was already there. I would try to draw animals and things when I was just a chipper—just a young lad. I used to drag in snakes and anything I could catch’.”

That curiosity quickly brought him into contact with professional scientists. Beebe recalled being the local authority whenever an “oddball” specimen appeared, including a large moth he captured and sent to the University of Alberta for identification. It was determined to be the Black Witch moth, a migratory species native to Mexico and known for travelling long distances. Through this exchange, Beebe began corresponding with a zoology professor at the University of Alberta, who invited him to meet and work alongside scientific collectors. “‘When you’re curious you make connections’,” Beebe later remarked. Through these relationships, he learned proper museum preparation techniques, obtained his first federal collector’s permit while still in high school, and began to move with increasing confidence between the worlds of field observation, scientific practice and illustration.

In the early 1930’s, at the age of 19, like many during the Depression Beebe left home seeking work. He traveled by freight train and eventually settled on Vancouver Island and worked mainly in relief camps. He took a variety of jobs, from harvesting and selling cascara bark to participating in field surveys for plague and fever among rats in B.C.

During this period, Beebe also sought out the artists whose work defined Canadian wildlife painting in the early twentieth century. Chief among them was Allan Brooks, widely regarded as the leading wildlife artist of the era, whose illustrations for Percy Taverner’s Birds of Western Canada were deeply admired by Beebe. Shortly after arriving on Vancouver Island in 1933, Beebe hitchhiked to Brooks’ home in Comox, determined to learn how he worked. There, he observed Brooks’ use of opaque colour, achieved by mixing pigments with tempera or Chinese white, and his preference for working on stretched pastel paper. When Beebe adopted these methods himself, he found that the quality and confidence of his paintings improved markedly—a technical lineage that can be seen in later works such as his grouse paintings, where dense colour, controlled opacity and careful surface preparation are central to their effect.

By the mid-1930s, Beebe had begun to transform his lifelong fascination with wildlife into professional work. His first steady, salaried position came at age 25, when he joined a biological field survey—an opportunity that allowed him to combine close observation in the field with his growing skills as an illustrator. “During the summer he rounded up rats, and during the winter he went into semi-hibernation, took odd jobs, and did some illustrating.” This period soon led him to Vancouver’s Stanley Park Zoo, where he was initially hired to control the rat population but eventually rose to the position of zoo manager.

Beebe’s most sustained and influential role began in the early 1950s at the British Columbia Provincial Museum in Victoria, where he rejoined the staff as Chief Illustrator and a museum technician. He would hold the position for nearly 22 years. Even from the beginning, in 1952, he was deeply embedded in the Museum’s daily operations, contributing far beyond conventional illustration work. He designed and prepared exhibit backgrounds, including a new-style display case for small mammals that featured white-footed mice in a carefully constructed beach habitat. Photographs from the period also show Beebe at work making a plaster cast of a common dolphin and mention him working directly with specimens, evidence of his hands-on approach and versatility.

At the same time, Beebe maintained an extraordinary output as an illustrator. He contributed illustrations to numerous provincial museum handbooks on birds, grasses, wildflowers and countless other flora and fauna. His drawings were grounded in field observation and close collaboration with the other museum employees like ornithologists, botanists and entomologists. Beyond formal publications, Beebe provided illustrations for a long-running series of weekly articles on local birds and mammals for the Victoria Daily Colonist. Across exhibitions, publications, fieldwork and many other formats, Beebe’s career at the provincial museum demonstrates how deeply intertwined art, science and public education were in his practice and how central he was during this period in shaping how the public encountered and understood the natural world.

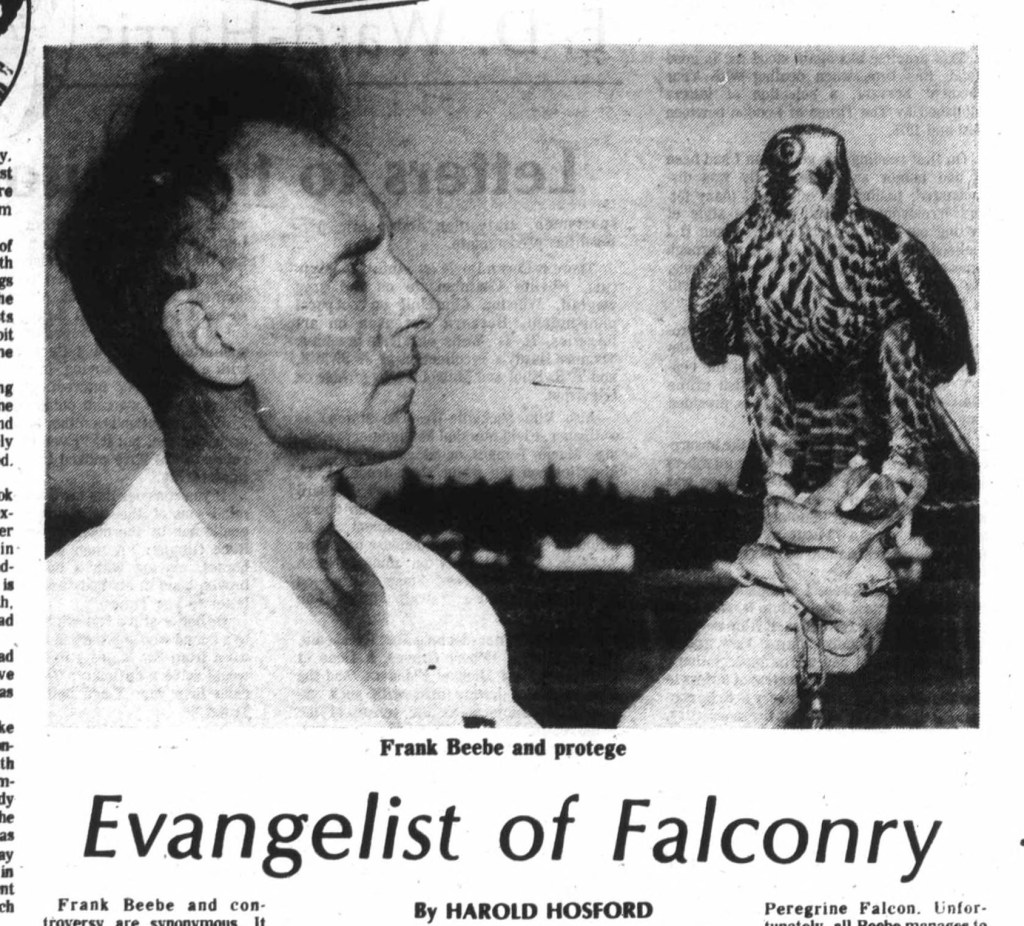

Beebe’s passion for birds continued to extend far beyond illustration. From his youth in Alberta, he was deeply engaged in studying raptors and other wildlife firsthand—raising owls and hawks, observing their behavior and training them to respond to calls. Beebe also made lasting contributions to falconry in North America.

He co-authored North American Falconry & Hunting Hawks (1964) with Hal Webster, the first North American guidebook on the subject, which remains a foundational text for falconers. He was also a co-founder of the North American Falconers’ Association (NAFA) and its first president, helping to establish organized falconry as a formal community across the continent and abroad. These roles highlight his influence in shaping both the practice and appreciation of raptor study, keeping and training in North America.

While some of Beebe’s writings—particularly regarding the conservation status of Peregrine Falcons—were unconventional, they reflect his independent spirit and the curiosity that drove both his falconry and his art. Across his work, whether in the field, in publications or through NAFA, Beebe combined artistic skill, scientific observation and leadership, leaving a significant imprint on both natural history illustration and the North American falconry community.

Although Frank Beebe spent much of his professional life in British Columbia, Alberta remained an important site for the circulation, sale, and exhibition of his work. Unlike many artists who relied on institutional commissions, Beebe also chose to sell his paintings through private art galleries, placing his work on consignment. Reflecting on the instability of this model, he remarked, “‘You have to watch private galleries because they go belly up so often. There’s constant change. A gallery that has good sales and is a good place to have your work today may be bankrupt tomorrow’.” Among the galleries that handled his work most extensively was the Gainsborough Gallery in Calgary, which had represented Beebe for the longest period of any private gallery before eventually closing.

Beebe’s presence in Alberta and its galleries extended beyond Calgary and the Gainsborough Gallery. Newspaper advertisements and exhibition listings place his work in Edmonton through the ‘70s and ‘80s, including displays in Edmonton at the Burlington Art Shop on Jasper Avenue and Lefebvre Galleries Ltd., where his paintings appeared alongside works by artists such as A.Y. Jackson, A.J. Casson and Carl Rungius. In mid-1989 and early 1990, his work was also exhibited in solo shows in Edmonton, at the Alberta Government Centre pedway and the Provincial Museum of Alberta (the former name of the Royal Alberta Museum), where The Art of Frank Beebe presented, “watercolours of birds and mammals in their natural habitats.” These exhibitions underscore the continued connection and resonance of his work in the province where he had grown up.

The framed Sooty Grouse painting now held by the Royal Alberta Museum bears a label from Kensington Fine Art Gallery Ltd., a Calgary gallery established in 1966 and active during the same decades in which Beebe’s work circulated through galleries in Alberta. While it remains unclear whether the painting was sold through Kensington or simply framed there, the label situates the object within Alberta’s commercial and cultural art network. The gallery’s involvement, however limited, forms part of the artwork’s material history, linking Beebe’s practice as a natural history illustrator to the province’s twentieth-century art market.

The painting entered the Royal Alberta Museum through a donation. Prior to its acquisition, the work had been held in private ownership and passed down through family. It was associated with a collector living in Banff in the 1960s, who owned several paintings by Beebe. Now preserved in the Royal Alberta Museum’s collection, the painting carries with it not only Beebe’s careful observation of the natural world but also traces of its journey through Alberta: gallery circulation, private ownership and eventual donation. Together, the image and its frame reflect the remarkable pathways through which art and objects survive, shaped as much by local businesses and individual collectors as by museums themselves.

Frank Beebe’s work reminds us of a time when scientific illustrators were essential figures within museums—translators between research and public understanding. Before high-resolution photography and digital visualization, illustrators like Beebe played a critical role in shaping how animals were studied, displayed and understood. Their images distilled observation, behaviour and anatomy into forms that could be shared with scientists, students and the public alike.

Yet this labour has often remained invisible. Illustrators, diorama artists, preparators and makers rarely occupy the foreground of museum histories, despite their deep influence on how collections were created and interpreted. Beebe’s career spanning fieldwork, publication, exhibition design, falconry and illustration offers a reminder that museums are built not only by skilled curators and researchers, but by the equally skilled practitioners whose knowledge is embodied and molded in craft.

The Sooty Grouse painting held by the Royal Alberta Museum is relatively modest in scale, but rich in meaning. It reflects a life shaped by close attention to the natural world, by movement between provinces, disciplines and institutions, and by a belief that careful looking matters. In remembering Beebe, we also remember the industrious, versatile, studious and essential museum workers whose hands and eyes shaped generations of understanding and whose contributions, once central, deserve continued recognition today.

Sources

Brown, Kira A (prepared Finding Aid). “Kensington Fine Art Gallery Fonds Finding Aid.” Online Finding Aid. 2011. Kensington Fine Art Gallery fonds. Library and Archives, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. https://www.gallery.ca/sites/default/files/documents/content/ngc117.html.

Dupuy, Mike. “The Passing of a Legend.” NAFA Journal (Wethersfield, Connecticut, U.S.A.), 2008; https://www.mikedupuyfalconry.com/marketing/pdfs/mdf_beebe.pdf.

Edmonton Journal (Edmonton, Alberta, Canada). “Gallery Glimpses.” Secs. C5, Edmonton Alive. July 27, 1989. Edmonton Journal (1903-2010), ProQuest Historical Newspapers, Access provided by the Edmonton Public Library.

“Gallery Glimpses.” Secs. D7, Edmonton Alive. August 31, 1989. Edmonton Journal (1903-2010), ProQuest Historical Newspapers, Access provided by the Edmonton Public Library.

Edmonton Public Library. Edmonton Journal (1903-2010) and Calgary Herald (1883-2010), ProQuest Historical Newspapers, Access provided by the Edmonton Public Library (EPL); https://www.epl.ca/resources-types/news-magazines/.

Guiguet, C. J. The Birds of British Columbia (4) Upland Game Birds. Reprint. Illustrations by Frank L. Beebe. British Columbia Provincial Museum Handbooks, No. 10. K. M. MacDonald, Queen’s Printer, Reprint: 1973. This was graciously donated by Dr. Gavin Hanke, the Curator of Vertebrate Zoology at the Royal BC Museum (RBCM) after conversing via email with the author. It now resides in the Royal Alberta Museum’s Reference Library.

Hanke, Dr. Gavin. “The Art of Science.” Staff Profile Articles. Royal BC Museum, April 16, 2014.

Herrick, Bob. “Frank L. Beebe: The Man Behind the Legend.” Wild Lands Advocate Vol. 10, no. No. 6 (2002): p.19;

Herrick, Bob, and Bill Murrin. “Frank Lyman Beebe.” Book of Remembrance Inductee, 2008. The Book of Remembrance. The Archives of Falconry, Boise, Idaho, U.S.A. https://remembrance.falconry.org/Beebe.pdf.

“Obituary: Frank Lyman Beebe.” International Falconer (Carmarthen, Wales, UK), 2009, p.4-6. The Falconry Heritage Trust, Carmarthen, Wales, UK;

Hosford, Harold. “Evangelist of Falconry.” Books. The Daily Colonist (Victoria, BC), October 30, 1976. Daily Colonist Newspaper Collection, p. 21. University of Victoria Libraries Collection, Victoria, BC, Canada;

Mortimore, G. E. “Frank Beebe: A Natural Born Naturalist (The Man of the Week).” Magazine. The Daily Colonist (Victoria, BC), July 27, 1952. Daily Colonist Newspaper Collection, p. 4. University of Victoria Libraries Collection, Victoria, BC, Canada;

Provincial Museum of Natural History and Anthropology. Report for the Year 1952. Annual Report. Province of British Columbia, Department of Education, 1953. Royal BC Museum, Victoria, BC, Canada. https://rbcm.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/annual_report_1952.pdf.

Report for the Year 1953. Annual Report. Province of British Columbia, Department of Education, 1954. Royal BC Museum, Victoria, BC, Canada.

https://rbcm.ca/wp content/uploads/2025/07/annual_report_1953.pdf.

Report for the Year 1955. Annual Report No. 1955. Province of British Columbia, Department of Education, 1956. Royal BC Museum, Victoria, BC, Canada.

https://rbcm.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/annual_report_1955.pdf.

Royal Alberta Museum (RAM). Frank L. Beebe Collection, H25.28. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Royal British Columbia Museum. Annual Reports Archive, Access provided by the Royal BC Museum; https://rbcm.ca/corporate-information/reports-policies/annual-report-archive/

Shutty, Myron. Frank L. Beebe, the Artist. Illustrations by Frank L. Beebe. Surrey, B.C.: Hancock House, 1992. Author used copy from the Royal Alberta Museum’s Reference Library.

University of Victoria. Daily Colonist Newspaper Collection, University of Victoria Libraries Collection, Courtesy of the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/dailycolonist and The British Colonist: https://www.britishcolonist.ca/index.html.

Vancouver Public Library. The (Vancouver) Province (1898-present) and Vancouver Sun (1912-present), ProQuest Historical Newspapers, Access provided by the Vancouver Public Library (VPL); https://www.vpl.ca/digital-library/british-columbia-historical-newspapers