Written by: Megan Bieraugle

People, dogs and wolves have had long and complex relationships, ranging from cooperation to competition. Alberta’s rich archaeological record includes many canids (mammals including dogs, wolves, coyotes and foxes), and understanding canid age at death can provide insights into their relationships with Indigenous people and how they vary geographically, temporally, and by species.

For example, assessments of dog age at death could be informative about how past people cared for their working animals as they aged beyond their prime years. In cases where dogs appear to have been kept primarily for use as food resources, ageing data could reveal how such populations were being managed, with individuals perhaps being slaughtered around 1–2 years of life once they reached full adult body size. Relationships with wolves also might be more fully understood with age-at-death information, particularly in North America, where they are often found in mass bison kill assemblages. Ageing data might reveal if whole packs were killed while scavenging human prey or if primarily young and inexperienced individuals met their fates in such settings. Finally, age-at-death information can be important for assessing aspects of canid life histories, including animals’ rates of tooth loss and fracture and their relationship to diet, but also experiences of degenerative joint disease and trauma. Despite their importance, methods for ageing archaeological dog and wolf remains are relatively limited.

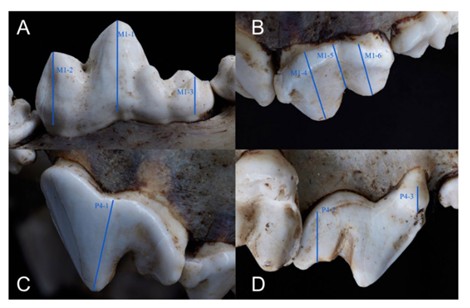

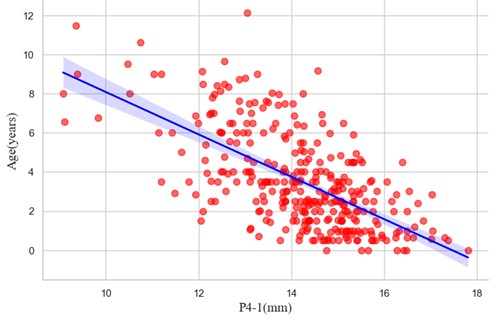

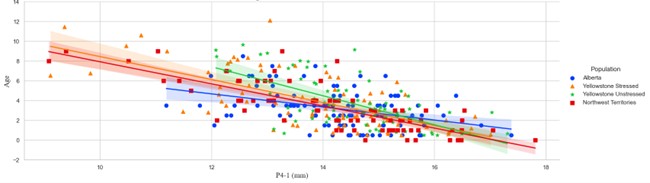

A recent study examined the relationship between tooth wear and ageing in a large sample of wolves from Alberta, Yellowstone National Park, and the Northwest Territories. They examined tooth crown height in cranial and mandibular carnassial teeth (the big pointy one!) to see how teeth get worn down with age. Results of the study suggested that as wolves age, their teeth begin to wear down—which makes sense! However, the variability observed in the relationships between tooth crown height and age likely has many contributing factors, some of which will be hard to constrain in most archaeological investigations.

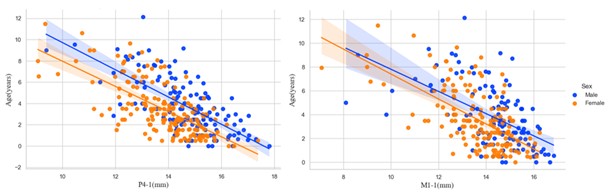

Factors such as where the wolves live can influence how fast their teeth wear, with the different populations experiencing different wear-rates. Though in the modern population, these differences are minor, they are suspected to be much more impactful in ancient populations. Size differences based on sex (with males typically being larger than females) may contribute to some pre-wear crown height variation. Male North American grey wolves are on average slightly larger than females in terms of both body mass and skeletal dimensions. However, our analyses indicated that both initial tooth size and rate of wear do not differ statistically by sex. In essence, when examining tooth-wear in wolves, you can ignore sex.

Finally, diet is also likely to play a role in the variation observed in tooth-wear. Reliance on larger-bodied prey potentially increases wear rates when compared to reliance upon smaller-bodied animals due to the former having larger and more robust skeletal elements. The diets of all wolves in the study likely focused on large ungulates, with some differences in primary prey occurring between each group. Wolves in Alberta potentially rely on elk, moose, and caribou, but may also prey upon cattle, horses, and sheep. The diets of the Yellowstone wolves have been monitored intensively since their reintroduction to the park in 1995. For both Yellowstone populations, elk are the most common prey, but they also utilize moose, deer, roadkill, and bison. The diet of wolves from the Northwest Territories commonly is comprised of caribou, but other large ungulates, small mammals, birds, and some marine species are also preyed upon. Unfortunately, it is difficult to explore these trends archaeologically without techniques such as isotope analyses.

Prey availability is an additional element of dietary variation that likely affects tooth wear rates more than diet composition. Dietarily stressed wolves are more likely to fully exploit their prey, increasing the consumption of bone and possibly tooth breakage or wear as well.

While there is no data to address the effects of a wolf’s social position, these, too, may influence rates of tooth wear. Long-standing periods of dominance might correspond to an individual carrying out less extensive carcass processing (less bone gnawing) due to having more consistent access to prime body parts. Conversely, extended periods of subordination might correspond to later access to carcasses, perhaps requiring more bone gnawing to extract nutrients. Such patterns would likely be exaggerated when prey availability is low.

Of course, this study has many implications for understanding ageing patterns in archaeological dogs as well. First, we should expect that dog body size variation in the past will exceed that of the wolves analyzed here. Modern dogs exhibit extreme variation in body size, and at least some of this variation emerged in the past. Second, given that dietary variation in modern wolves, including differences in prey body size and availability, may impact tooth wear rates, we should expect that dietary variation in past dogs will be equally impactful, if not more so. In some regions, ancient dog dietary structure (major groups of food in the diet) has been shown to have far exceeded that of contemporaneous wolves. Further, many past dogs likely relied on a mixture of scavenging and being fed by humans, causing significant variation in the qualities of the food they consumed. For example, food textures would have been highly variable in the past, with some dogs being fed soft foods such as fish while others were dependent upon grain or even difficult-to-process refuse such as discarded bones.

Such conditions could vary even between contemporary households but also as changes in the human food environment shifted due to season, climate, and numerous other factors. In short, we should expect the complexities of dog diets in the past to create more variable relationships between tooth crown heights and age than observed in our modern wolf populations. Finally, changes in selection that emerge through domestication also may affect tooth wear patterns in dogs. A decrease in body size over time, a common pattern observed in mammal domestication, should reduce sexual size dimorphism (Rensch’s rule). In at least modern dogs, sexual size dimorphism has been found to generally decrease with decreases in body size. If the same patterning existed in past dogs, the minor sex-based differences in tooth size observed in our modern wolves would be reduced. Further, in ideal settings, average life expectancy in domestic dogs could be significantly higher than in wild wolves. Human care and provisioning could allow dogs to survive beyond the point at which their dentition remained functional.

Understanding canid age at death in relation to tooth wear needs to be further explored in other canid species and with additional reference data. For ageing methods based on tooth wear, approaches focusing on specific, localized regressions, with body size, dietary variation, and sex taken into account will prove most accurate. Developing additional ageing methods is warranted and such efforts should improve our ability to make compelling interpretations of archaeological canid remains, including their variable interactions with humans.

For more details, the full study can be found here.

Sources

Abouheif, E. and Fairbairn, D. (1997). A comparative analysis of allometry for sexual size dimorphism: assessing Rensch’s rule. Am Nat 149: 540–562.

Bieraugle, M., Ding, L., Cluff, H. D., Jutha, N. and Losey, R. J. (2024). Ageing wolves through crown height measurements and its implications for ageing canids. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 16: 157.

Bjorge, R. and Gunson, J. (1985). Evaluation of wolf control to reduce cattle predation in Alberta. J. Range Manage 483–487.

Frynta, D., Baudysˇova, J., Hradcova’, P., Faltusova’, K. and Kratochvı’l, L. (2012). Allometry of Sexual Size Dimorphism in Domestic Dog. PLos ONE 7:.

Guiry, E. (2012). Dogs as Analogs in Stable Isotope-Based Human Paleodietary Reconstructions: A Review and Considerations for Future Use. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 19: 351–376.

Hillis, T. L. and Mallory, F. F. (1996). Sexual dimorphism in wolves (Canis lupus) of the Keewatin District, Northwest Territories, Canada. Canadian Journal of Zoology 74: 721–725.

Huggard, D. J. (1993). Effect of Snow Depth on Predation and Scavenging by Gray Wolves. The Journal of Wildlife Management 57: 382.

Kortello, A. D., Hurd, T. E. and Murray, D. L. (2007). Interactions between cougars (Puma concolor) and gray wolves (Canis lupus) in Banff National Park, Alberta. Ecoscience 14: 214–222.

Krozser, K. (1991). Canid Remains at Kill Sites: A case study from the Oldman River Dam project. In M. Magne (ed.), Archaeology in Alberta 1988 and 1989, Archaeological Survey of Alberta, Edmonton, pp.81–100.

Kuyt, E. (1972). Food habits and ecology of wolves on barren-ground caribou range in the Northwest Territories. Canadian Wildlife Service Report Series 21:.

Lamothe, A. R. and Parker, G. H. (1989). Winter feeding habits of wolves in the Keewatin District, Northwest Territories. Musk-Ox 37: 144–149.

Landals, A. (1986). The Maple Leaf Site: An Interpretation of Prehistoric Hunting and Butchering Strategies in the Southern Alberta Rockies., Unpublished Masters Thesis, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

Larter, N. C. (2013). Diet of Arctic wolves on Banks and Northwest Victoria Islands, 1992-2001.

Losey, R. J., Drake, A. G., Ralrick, P. E., Jass, C. N., Lieverse, A., Bieraugle, M., Christenson, R. and Steuber, K. (2022). Dogs and Wolves on the Northern Plains: A Look from Beyond the Site in Alberta. Journal of Archaeological Science 148: 1–12.

Lupo, K. D. (2019). Hounds follow those who feed them: What can the ethnographic record of hunter-gatherers reveal about early human-canid partnerships? Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 55: 1–14.

MacKinnon, M. (2010). ‘Sick as a dog’: zooarchaeological evidence for pet dog health and welfare in the Roman world. World Archaeology 42: 290–309.

McHugh, T. and Hobson, V. (1972). The time of the buffalo, University of Nebraska Press.

Morehouse, A. and Boyce, M. (2011). From venison to beef: seasonal changes in wolf diet composition in a livestock landscape. Front Ecol Enviro 9: 440–445.

Morris, J. S. and Brandt, E. K. (2014). Specialization for aggression in sexually dimorphic skeletal morphology in grey wolves (Canis lupus). Journal of Anatomy 225: 1–11.

Ralrick, P. E. (2007). Taphonomic Description and Interpretation of a Multi-Taxic Bonebed at Little Fish Lake, Alberta, Canada. Unpublished master’s thesis., University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

Speakman, J., van Acker, A. and Harper, E. (2003). Age-related changes in the metabolism and body composition of three dog breeds and their relationship to life expectancy. Aging Cell 2: 265–275.

Van Valkenburgh, B., Peterson, R. O., Smith, D. W., Stahler, D. R. and Vucetich, J. A. (2019). Tooth fracture frequency in gray wolves reflects prey availability. eLife 8: e48628.

Van Valkenburgh, B. and Sacco, T. (2002). Sexual dimorphism, social behavior, and intrasexual competition in large Pleistocene carnivorans. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22: 164–169.

Walker, D. N. and Frison, G. C. (1982). Studies on Amerindian dogs, 3: Prehistoric wolf/dog hybrids from the northwestern plains. Journal of Archaeological Science 9: 125–172.

Williams, M. (1990). Summer diet and behaviour of wolves denning on barren-ground caribou range in the Northwest Territories, Canada, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta.