The 100th anniversary of the Calgary Exhibition and Stampede came to a close this past Sunday, July 15, 2012. Today’s blog post will complete the short series about the Big Four and the geographical features named for them. The Big Four were the ranchers and businessmen that funded Guy Weadick’s 1912 wild west show and rodeo, which grew to become today’s Calgary Stampede. Part One of our series was posted on July 10, 2012 and featured Stavely area rancher George Lane and Lane Creek; Part Two was about A. E. Cross and Cross Creek. Today’s post will feature Calgary-based rancher and industrialist Patrick Burns.

Pat Burns: Rancher, Businessman, Industrialist and Senator

Pat Burns is arguably the most successful and well-known of the Big Four. Pat Burns was born and raised in the Lake Simcoe region, near Oshawa, Canada East (later Ontario) in 1856. He migrated west in 1878 and tried his hand at homesteading in Manitoba. While homesteading, he acquired some oxen and hired himself out as a freighter. He also dabbled in livestock trading. Encouraged by the Canadian Pacific Railway, which wanted to prove the viability of long-distance livestock shipments, Burns bought six carloads of hogs and had them shipped east; the venture was profitable. Seeing greater opportunities in livestock trading, Burns abandoned the homestead in 1885 and began trading cattle full-time.

In 1887, Burns was contracted to provide meat to railway construction camps, and within two years he was supplying camps from Maine in the east to Calgary and Edmonton in the west. He established a slaughterhouse in Calgary in 1890 and established a ranch, the first of many, near Olds the following year. In 1902, Burns acquired from William Roper Hull a chain of retail stores and the associated the Bow Valley Ranche (now a Provincial Historic Resource) on Fish Creek south of Calgary. Burns’ company, P. Burns and Co., soon became one of Canada’s largest meat-packing companies, with production facilities and retail stores across the west. It also maintained up to 45,000 head of cattle on numerous ranches in central and southern Alberta, including the Bar U and the Flying E, which were acquired following the death of George Lane in 1927. Burns diversified his company’s investments by successfully expanding into dairy production and fruit and dry goods distribution and, less successfully into the American dairy market and into coal and copper mining and oil and gas exploration.

Burns was active in the community and was a noted philanthropist, providing funding to schools, hospitals, orphanages, old-age homes and widows’ funds. He was also known to send train loads of food to disaster stricken areas. Burns, a supporter of the Liberal Party, was appointed to the Canadian Senate by Conservative Prime Minister, R. B. Bennett; Burns sat as an Independent from 1931 until 1936, when he retired due to health reasons. Pat Burns died on February 24, 1937 at Calgary.

Two geographical features in Alberta are named directly for Patrick Burns, although four features bear his name (Confused? Bear with me).

Mount Burns

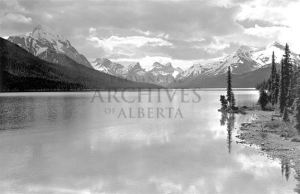

Mount Burns is an approximately 2,940 metre (9635’) mountain on the north side of the Sheep River about 40 km west of Turner Valley. In the 1910s, coal had been discovered in Sheep River Valley below this mountain and, in 1913, Pat Burns invested in a coal mine alongside the river. According to historian Grant MacEwan, Burns visited the mine site frequently. The Geological Survey of Canada recommended that the mountain be named Mount Burns, due to the nearby mine and its association with the Calgary businessman. The name was officially adopted by the Geographical Board of Canada On May 2, 1922 and began appearing on federal government maps, such as the 1926 Calgary Sectional Sheet, soon after that.

National Topographic System Map Sheet: 82 J/10 – Mount Rae

Latitude/Longitude: 50° 38’ 39” N & 114° 51’ 40” W

Alberta Township System: Sec 26 Twp 19 Rge 07 W5

Description: On the north side of the Sheep River Valley, approximately 40 km west of The Town of Turner Valley

Burns Creek

Burns Creek flows off the eastern slopes of the Mount Rae/ Mount Arethusa massif. The creek flows south-easterly off the mountain face into the northern end of a small, high altitude lake (Burns Lake) approximately 1.7 hectares (4.25 acres) in size. The creek exist the south side of the lake and proceeds south-east and then north-east until it meets Rae Creek to form the Sheep River. The creek is approximately eight km in length.

Not much is known about the naming of Burns Creek. The creek is named on the 1926 Calgary Sectional Sheet and it is most certainly named due to its association with the nearby mountain and coalmine. Mountains often lend their names to associated geographical features, such as creeks and lakes. Typically, these creeks run directly off the mountain. For example, Storm Creek runs off Storm Mountain and Warspite Creek runs off Mount Warspite. However, in the case of Burns Creek, the creek is not directly associated with Mount Burns, but is located on the opposite side of the sheep River Valley.

National Topographic System Map Sheet: 82 J/10 – Mount Rae

Latitude/Longitude: 50° 37’ 00” N & 114° 57’ 58” W (approximate location of head waters) to 50° 37′ 25″ N & 114° 53′ 25″ W (at confluence with Rae Creek and Sheep River)

Alberta Township System: SW ¼, Sec 19 Twp 19 Rge 7 W5 (approximate location of head waters) to NS ¼, Sec 22 Twp 19 Rge 7 W5 (at confluence with Rae Creek and Sheep River)

Description: Flows off the east face of Mount Rae and Mount Arethusa for eight km until it meets Rae Creek to form the Sheep River about 45 km west of the Town of Turner Valley.

Burns Lake (1)

Burns Lake is both fed and drained by Burns Creek. It was not officially named until the 1980s. In the mid 1980s, Alberta Fish & Wildlife made plans to stock this lake with fish. Information about the lake would be published in the stocking program’s reports and possibly in tourist and angling literature. A Fish & Wildlife officer familiar with the region recommended that the name Burns Lake be officially adopted. This proposal met with the approval of the Citizens’ Action Committee on Kananaskis Country on March 5, 1985 and by the Alberta Historical Resources Foundation on November 14, 1986 and by the Minister of Culture on May 5, 1987.

National Topographic System Map Sheet: 82 J/10 – Mount Rae

Latitude/Longitude: 50° 36′ 16″ N & 114° 56′ 38″ W

Alberta Township System: Sec 29 Twp 31 Rge 27 W5

Description: On the south side of the Sheep River Valley, approximately 47 km west of the Town of Turner Valley.

Burns Lake (2)

The second Burns Lake in Alberta is located near the Town of Olds. It is approximately 22 hectares (54 acres) in size. It is located in the County of Mountain View, about 25 km south east of the Town of Olds and 22 km east of the Town of Didsbury. Pat Burns operated ranches in the general vicinity of this lake. In 1922, S. L. Evans of the Dominion Land Survey recorded the name of the lake as Burns Lake on the plan he drew for Township 31-27-W4. The name was officially adopted by the Geographic Board of Canada for mapping purposes on January 20, 1955.

The second Burns Lake in Alberta is located near the Town of Olds. It is approximately 22 hectares (54 acres) in size. It is located in the County of Mountain View, about 25 km south east of the Town of Olds and 22 km east of the Town of Didsbury. Pat Burns operated ranches in the general vicinity of this lake. In 1922, S. L. Evans of the Dominion Land Survey recorded the name of the lake as Burns Lake on the plan he drew for Township 31-27-W4. The name was officially adopted by the Geographic Board of Canada for mapping purposes on January 20, 1955.

National Topographic System Map Sheet: 82 P/12 – Lonepine Creek

Latitude/Longitude: 51° 41′ 13″ N & 113° 48′ 09″ W

Alberta Township System: SW ¼, Sec 17 Twp 19 Rge 7 W5

Description: In Mountain View County, approximately 25 km south-east of the Town of Olds.

Additional Resources:

More information about Senator Pat Burns can be found at:

Elofson, Warren, “Burns, Patrick,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, edited by John English and Réal Bélanger, Vol. XVI, available from http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?id_nbr=8428&PHPSESSID=bcpbd4hg2slsgaa1bkv04sukr5.

“Senator Patrick Burns”, Calgary Business Hall of Fame, , available from http://www.calgarybusinesshalloffame.org/bio.php?page=laureates/2009/PatrickBurns.php.

MacEwan, Grant, Pat Burns, Cattle King, (Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1979)

Archie McLean

You may have noticed that this is a series about the Big Four, yet there were only three parts, George Lane and Lane Creek; A. E. Cross and Cross Creek; and Pat Burns and Mount Burns, Burns Creek and two Burns Lakes. What about the other member of the Big Four?

The other member of the Big Four that funded the Calgary Stampede was Archibald “Archie” McLean. McLean was arguably just as successful as his three contemporaries, he was a successful rancher in the Taber and Fort Macleod regions, was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Alberta in 1909, 1913 and 1917. However, unlike his three contemporaries, there are no geographical features named for Archie McLean. A bridge on Highway 864 crossing the Oldman River just outside of Taber is named for him (49° 48’ 48”N & 112° 10’ 15”W) and there is a small lake just east of Lethbridge that is locally known by some as “McLean Lake” (49° 41’ 47” N & 112° 45’ 22” W).

For information about Archie McLean can be found on a recent blog post by Lethbridge’s Galt Museum & Archives, which can be accessed at:

http://galtmuseum.blogspot.ca/2012_06_01_archive.html.

Written by: Ron Kelland, Historic Places Research Officer and Geographical Names Program Coordinator