Hot off the virtual presses is the revised and updated Geographical Names Manual. It is now available on the Alberta Geographical Names Program website.

What is the Geographical Names Manual?

The Geographical Names Manual is the guiding document for naming geographical features in Alberta. It contains a brief history of geographical naming in Canada and Alberta; it identifies and describes the legislation covering geographical naming; and it outlines the roles and responsibilities of the Alberta Historical Resources Foundation and the Alberta Geographical Names Program in geographical naming matters. It also outlines the research done by the Geographical Names Program and attempts to demonstrate the high standards of research and evidence that are required before names are adopted for use on official maps in Alberta.

The Geographical Names Manual is the guiding document for naming geographical features in Alberta. It contains a brief history of geographical naming in Canada and Alberta; it identifies and describes the legislation covering geographical naming; and it outlines the roles and responsibilities of the Alberta Historical Resources Foundation and the Alberta Geographical Names Program in geographical naming matters. It also outlines the research done by the Geographical Names Program and attempts to demonstrate the high standards of research and evidence that are required before names are adopted for use on official maps in Alberta.

Most importantly, the manual contains the “Principles of Geographical Names.” These principles are used by the Alberta Geographical Names Program to evaluate proposed names for geographical features and proposed changes to existing names before presenting naming proposals to the Foundation for consideration. The Principles are largely based on those used by the Geographical Names Board of Canada, which in turn are based on long-standing, international naming policies and procedures. These international standards have been developed since regulatory bodies were first established to oversee geographical names, more than a century ago.

Why do we need the Manual and its Principles and Standards?

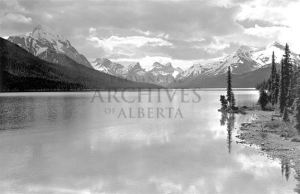

Standardized principles and procedures for the adoption and revision of official names were developed to ensure a high a level of consistency in land-marking and map-making over time and across jurisdictions and cultures. Maps, whether paper-based or electronic, are an essential navigational tool. For this reason it is essential that the names that appear on these maps are accurate and consistent so that navigation is efficient and free of confusion. However, as human beings, it is also natural for us to want to name our surroundings, thereby affirming our place amongst our geography, identifying features important to us and commemorating our history and our evolving cultural values. The established standards, principles and procedures that have been developed over time are an attempt to balance the need for consistency with our desire to name the landscape.

Most people are unaware that there are naming standards and a process for the adoption of official names. The intention of the manual is to make the standards, principles and procedures available to the general public in a format that is accessible and understandable.

People considering making an application to have a new name adopted for a geographical feature or proposing a change to an existing name are encouraged to read the Manual, particularly the “Principles of Geographical Names” section. An understanding of the Principles can save substantial effort and make the process much clearer and easier to understand.

Why was the Manual updated?

The Geographical Names Manual was first published in 1987 (reprinted in 1989). A second revised edition was published in 1992 and a third edition in the early 2000s. Since the publication of the third edition, some of the basic information, such as the Department/Ministry name, Government of Alberta logos, etc. had become significantly outdated. As these details needed to be updated, the opportunity was ripe to give the entire Manual an overhaul. Revisions included:

- Enhancing the format and style, making the document more attractive and interesting by taking advantage of current word-processing tools;

- Expanding the Introduction section to include answers to some of the frequently asked questions about naming;

- Expanding the History section to provide more context of how place naming in Canada and Alberta has evolved;

- Minor editing of the “Principles of Geographical Names” to improve readability;

- Expanding the Standards of Research section to provide more information about the importance of sources of evidence and to provide links to other guides and information;

- Revising the Procedures section to better reflect the path taken by naming proposals from receipt of application to official rejection or adoption of the proposed name.

The most significant change was the addition of sections explaining naming procedures in areas where the Government of Alberta shares jurisdiction over naming matters – National Parks (with Parks Canada), Canadian Forces Bases (with the Department of National Defence), and Indian Reserves (with the Aboriginal and Northern Affairs Canada and the affected First Nations tribe, band or community). Also added were sections explaining the naming procedures for features that lie on or cross an inter-provincial boundary into Saskatchewan, British Columbia or the Northwest Territories or for features that cross the international border into the state of Montana.

So, there it is. The new and improved Geographical Names Manual is available as a PDF on the Geographical Names Program website.

We hope that all Albertans interested in our province’s naming heritage will find this revised edition of the manual useful, interesting and educational. In the near future the Geographical Naming Application form and the webpage itself will also be updated.

Written by: Ron Kelland, Historic Places Research Officer and Geographical Names Program Coordinator