Written by: Julia-Rose Miller, Honours Undergraduate, U of A Department of History, Classics and Religion

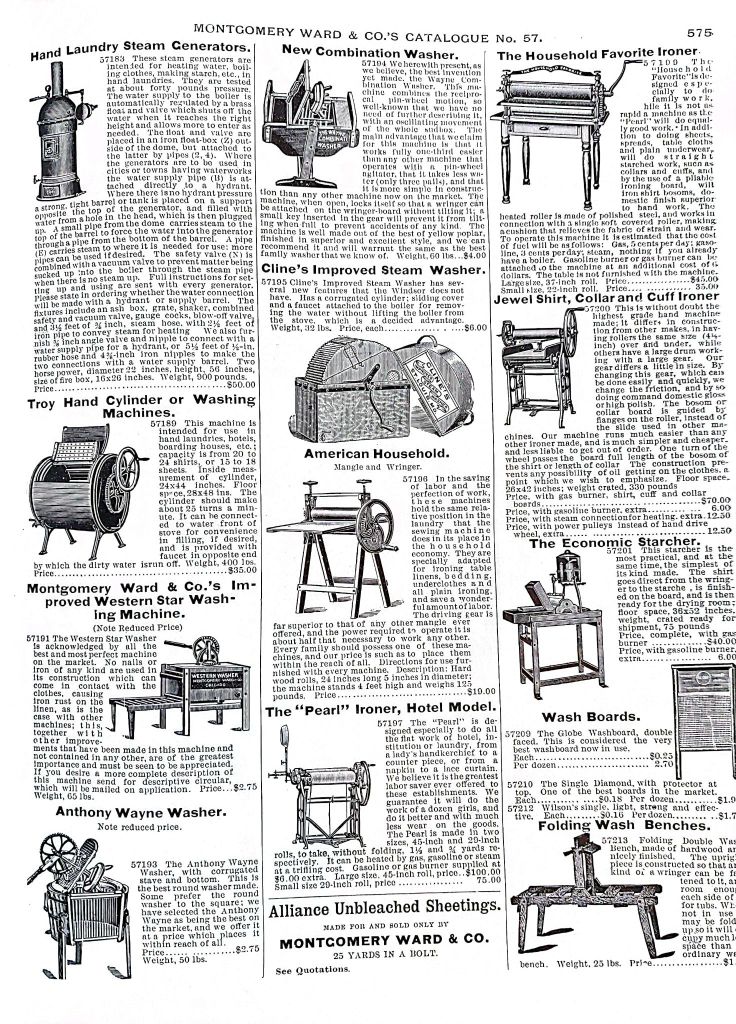

Laundry has always been among humanity’s greatest burdens. In the past, much like today, clothing had to be washed, bleached, starched, ironed and dried. However, historically, a household’s clothing was by far their most expensive and precious domestic possessions. This meant that the maintenance and laundering of clothing was even more crucial, even though households were likely not in possession of all of our modern cleaning chemicals and detergents. Laundry in Pakan was no different from other areas of Canada at this time as they had access to all the ‘modern amenities’ (hand cranked washing machines, wringers, mangles, irons, clothes lines, laundry tubs, washboards, wash boilers, ironing boards and clothes horses) via catalogues.

Studying domestic labour is at times rather complicated, because, like many other pieces of women’s work, there are few written records detailing laundry activities. To deal with the lack of Pakan-specific sources, my examination of laundry centered on images from Pakan in conjunction with other resources from different parts of Canada like the Eaton’s catalogues and household manuals. Images from Pakan established that residents were wearing western-style, cloth-based textiles, suggesting that they would likely also be using European laundering techniques developed for these articles of clothing. Annie B. Juniper’s Girls’ home manual of cookery, home management, home nursing and laundry provided a comprehensive explanation of numerous laundering techniques and materials popular at the turn of the century. This book, published in Victoria, B.C. in 1913, was given to school girls to instruct them on proper methods for home maintenance.

The process of laundering as revealed in the manual, was far more laborious than today even though washing machines had already been invented. Provided they had the funds to afford them, washing machines were readily accessible to the women of Pakan through catalogues. These machines were most often hand cranked, and drying clothes required the use of a wringer or mangler which was also hand cranked. Soaps at the time were not liquid based as they are now; most were often sold as powders or tablets. There is also some evidence that women would have made their own soaps known as bark (made from plants) or oxgall (which was made of fat often received from a butcher) when they could not access commercial soaps.

In addition to soap, many additives (including but limited to borax, lye, starch, ammonia, washing soda, blue, vinegar, salt, alum, turpentine and gasoline) could be added to laundry to achieve various desired outcomes. Some of these uses included vinegar to maintain vibrant colours, blueing to preserve the bright whiteness of fabric and gasoline to clean delicate fabrics which might be damaged by soaps. The most important additive from this list for laundering on the prairies, however, was washing soda used to soften water. Starch was another essential additive, as it was used to stiffen garments—particularly men’s collars. Moreover, much like the use of bark or oxgall during a soap shortage, in the absence of boxed starch for stiffening garments women could use water which was rinsed from starchy foods such as rice or potatoes.

The combination of recommendations from the Girls’ home manual, the presence of catalogues and pictures of locals demonstrate access to washing amenities in the prairie west and suggest a similar system of domestic labour to other, more settled regions of Canada. However, while women certainly had access to all of the modern laundering comforts, the instructions on what to do in their absence show the need for adaptability. Pakan is but one example of this phenomenon and studying laundry within its borders, rather than revealing the life of Pakan in particular, tells a story of Alberta women in early settler society.

Sources

Ingun Grimstad Klepp, “Care and Maintenance,” in Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: West Europe, ed. Lise Skov. trans. Stig Erik Sørheim and Kjetil Enstad (Oxford: Berg 2010), 169.

Annie B. Juniper, Girls’ home manual of cookery, home management, home nursing and laundry, (Victoria, British Columbia: Printed by W.H. Cullin, 1913): 157.

Juniper, Girls’ home manual of cookery, 157-161.

Juniper, Girls’ home manual of cookery, 159.

I remember as a child visiting my grandmother’s house in Calgary. We would always explore the house even though it was tiny by today’s standards. She lived on a farm in Saskatchewan prior to their retirement in Calgary. We would inevitably find the lye soap. It was a mysterious thing to us as children. We knew by the name that it was soap but we didn’t understand why it was different from the bar soap that we saw in the bathrooms upstairs. Why was it in the basement and where did it come from. Such things held no end of interest to us. That was in the late 60s.

I have reearched Annie Juniper for a number of years, mainly for her involvement in home economics and education. Teaching girls about laundry was a focus in girls’ education up to about grade 7, and not many people went beyond grade 8.

It’s nice to see Julia-Rose Miller’s interest in this topic. BC Food History has some articles about utilities and home economics, not just laundry.

https://bcfoodhistory.ca/utility-companies-home-economists/

Living on a farm in Manitoba as a child, laundry soap was lye soap because we had (everyone had) plenty of animal fat from pigs (usually) that were slaughtered for eating. You “rendered the fat” and made soap. Washing soda was however pretty well unknown because for laundry one wanted soft water which meant rain water or water melted from snow in winter. Most houses had large rain barrels or cisterns where rain water could be stored and this “soft” water was used for washing.