Written by: Sam Judson and Lindsay Amundsen-Meyer, Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Calgary.

Alberta’s cowboy culture is embraced by many and celebrated through events and conventions like the Calgary Stampede, K-Days or Calgary’s ‘White Hat’ tradition. This culture is largely represented in the history books by white, European settlers, although Alberta’s past is much more multiethnic and multicultural than many realize.

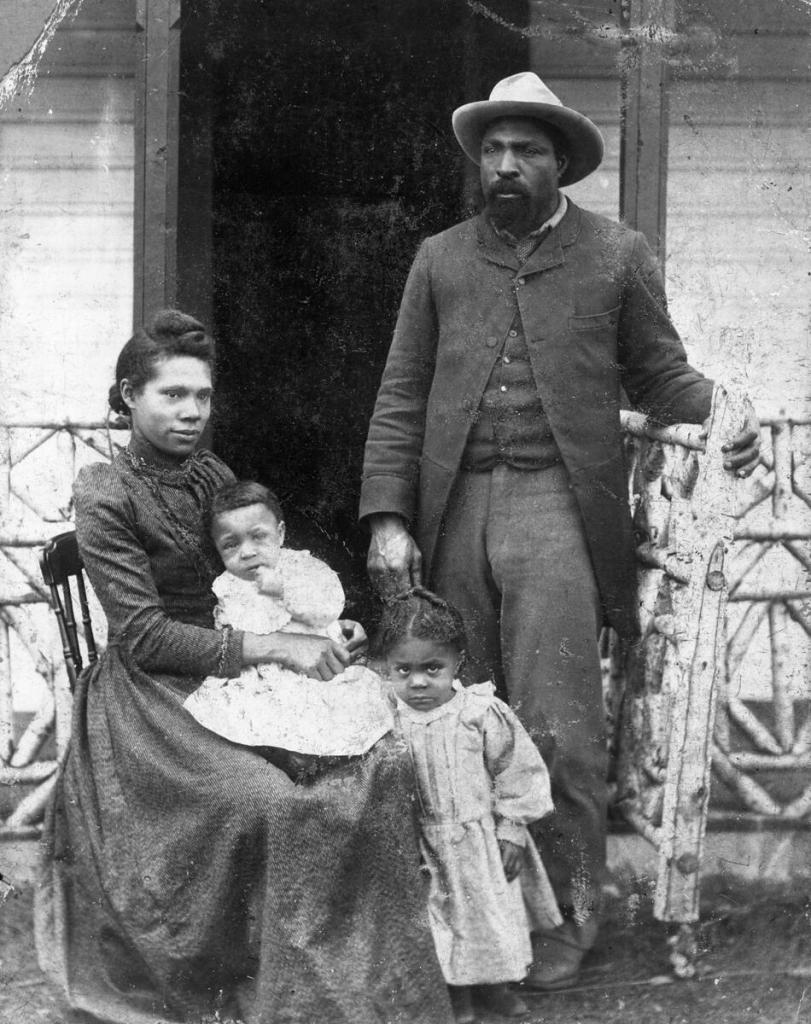

John Ware was one of Alberta’s early Black setters. Ware’s name is recognizable today to many Albertans, who refer to him as Alberta’s first Black cowboy, and the longevity of his legend is fascinating. Despite this, few know his story and very little is known about the true nature of his life.

Most sources suggest Ware was born into slavery in North Carolina. He found ranching work in Texas before being hired in 1882 as part of a trail crew bringing 3,000 head of cattle from the United States to Canada for the Northwest Cattle Company, headquartered at the Bar U Ranch. Ware remained on the Alberta prairies working for the Bar U Ranch, Quorn Ranch and several other large cattle companies. Ware established his own ranch near Millarville in the late 1880s, where he lived with his wife, Mildred, and their five children. In 1901, the Ware family relocated to a homestead near Duchess, where they remained until Mildred’s and John’s untimely deaths in 1905.

The true nature of Ware’s life is difficult to discern from the legends built around him. Few contemporary historic records exist, limited to homestead records and announcements of John and Mildred’s marriage, the birth of their children, and the deaths in the family. Most stories about John Ware were written by his fellow cowboys or his daughter Nettie some 20 or 30 years after his death. These stories speak of John in a legendary capacity, referring to him as someone who could lift any weight, wrestle any steer or ride any horse that his contemporaries could not. These stories speak to the regard he earned from his peers. This is provocative because minorities were not necessarily seen as or treated as equals in the Eurocentric society of 19th and early 20th Century Southern Alberta. In cases such as this, archaeology can help to provide a bottom-up viewpoint of daily practice and lived experience, as opposed to representations in historic records.

In 2017, Lindsay Amundsen-Meyer (then at Lifeways of Canada Limited) completed archaeological research at Ware’s homestead (EePo-29), as part of Cheyrl Foggo’s film John Ware Reclaimed. This work uncovered hand-forged horseshoes, sawn cow-bone and square nails suggestive of Ware’s time there, which planted the seed for future research. In the summer of 2024, a team of researchers from the University of Calgary and the University of Alberta teamed up with Cheryl Foggo and landowner Steve Fisher to undertake an archaeological field program at Ware’s Millarville homestead, with the goal of identifying the location of the house or other buildings and features.

Over three days in July 2024, the team conducted geophysical surveys, flew drone-based LiDAR and other imaging, dug shovel tests, and opened two preliminary excavation units. University of Calgary researchers and students worked with graduate students from the Institute of Prairie and Indigenous Archaeology (IPIA) at the University of Alberta, who specialize in non-invasive, remote-sensing and geophysical techniques. Using these technologies allowed researchers to gain an understanding of the landscape and what may be present below the ground, without disturbance or excavation, and helped to target subsurface excavations.

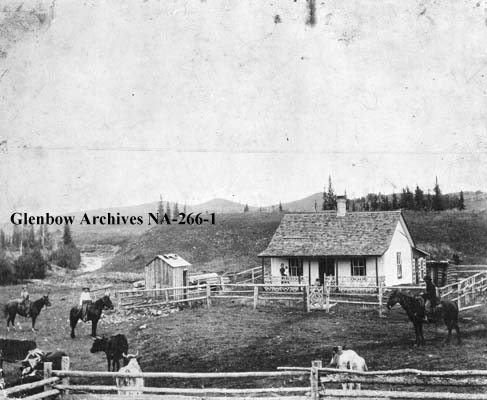

While ground penetrating radar did not detect any potential buried foundations, results of the magnetic gradiometry survey were suggestive of areas of concentrated buried metal objects, including around a rather square-looking depression on the west side of the field. The location of this depression is roughly consistent with where historic photographs depict Ware’s cabin, near the visible remains of his irrigation ditch.

Based on this, researchers settled on this unnatural, depression (approximately 6-8 meters) as the most likely location of Ware’s home. In a historical archaeological context, depressions such as this often represent the cellar or basement that would have been dug underneath a home. In this case, researchers hypothesize it was the cellar of a home. No one has lived on this quarter-section since the Ware family. Therefore, any historic structures or domestic debris found in the area can be reasonably understood as having belonged to or been occupied by the Ware family.

Two excavation units were placed within and adjacent to the identified depression, in hopes of clarifying if it is, in fact, a structure. Additionally, 12 shovel tests (40 cm by 40 cm) were excavated in various areas around the Ware homestead. The location of shovel tests was chosen based on the proximity to the cellar depression, smaller visual surface depressions (outhouse?), the hypothesized location of various outbuildings based on historic photographs, or on data collected in the geophysical surveys (barn?).

Belongings recovered from Ware’s homestead in 2024 include square nails, cattle bone, fragments of metal and glass, charcoal and coal, and fragments of ceramic tableware. Square nails, which were machine cut in a rectangular shape, are certainly older than 1910 and most likely pre-date 1900, when round wire drawn nails become most common. This makes them an important artifact to find because these dates align with when Ware homesteaded in this area, from the late 1880s (ca. 1888) to 1901. Pieces of ceramic dinnerware were also an exciting find as they feature a blue design which can potentially be dated. The excavation within the hypothesized cellar depression was particularly rich, containing square nails, fragments of barbed wire, historic bottle glass, a historic button with fiber still attached, and the most exciting find – an almost complete steer skull. This skull was recovered approximately 70 cm below the modern surface and may have been dispatched by a firearm shot to the forehead. Overall, research completed at the Ware homestead (EePo-29) demonstrates that significant, intact cultural material (belongings) and features are present at the site and are worthy of further research.

This work, although very preliminary, is an important step in amplifying the stories of the diverse cultures and individuals who played a role in creating Alberta’s ranching and cowboy culture. It also demonstrates the important role that archaeology can have in elevating the lives, voices and impacts of minority individuals in Alberta’s history. Through the inclusion of Cheryl Foggo and other members of the Black community in this research, our team has seen the emotional impacts research on Black heritage can have in modern day communities. This was demonstrated by Cheryl during 2024 work at the Ware Homestead site, when she stated: “This place has a powerful emotional connection, a powerful draw and pull for people of African descent…I am walking with the ghosts of John Ware and his family, even now.”

John Ware and his family are only one of the many, many Black families that settled in Alberta. As we learn more about John Ware and his family, life, and role in late 1800s and early 1900s Alberta, we can shine a light on and celebrate Alberta’s multicultural and multiethnic history as well as the role of diverse Albertans in forming our modern Western culture. This work was an incredibly important first step in learning more about John Ware’s life, but this work is far from complete. Researchers hope to return to the Ware homestead in 2025 to continue this work.

Sources

Anon

2022, John Ware. Canadian Encycopledia.

Glenbow Museum

2006, Mavericks: An Incorrigible History of Alberta. John Ware.

Foggo, Cheryl

2020, John Ware Reclaimed. National Film Board, Canada.

High River Pioneers and Old Timers Association

1960, Leaves from the Medicine Tree: A History of the Area Influenced by the Tree, and Biographies of Pioneers and Oldtimers Who Came Under its Spell Prior to 1900. Lethbridge Herald, Lethbridge, Alberta.

Kaufmann, Bill

2024, ‘Walking with Ghosts’: Cowboy John Ware’s Homestead Unearthed Near Millarville. Calgary Herald.

Kelly, Jennifer

2024, Black Communities in Alberta. Alberta Labour History.

MacEwan, Grant

1960, John Ware’s Cow Country. Institute of Applied Art Ltd., Edmonton, Alberta.

Millarville, Kew, Priddis and Bragg Creek Historical Society

1975, Our Foothills. Millarville, Kew, Priddis and Bragg Creek Historical Society, Calgary, Alberta.