Editor’s note: All images in this post were taken by Suzanna Wagner. The image above is of a view across the Stromness Harbour, Orkney.

Written by: Suzanna Wagner, Program Coordinator, Victoria Settlement and Fort George & Buckingham House

Have you ever travelled vast distances only to find pieces of home?

Intent on exploring new vistas, seeing the ocean, and walking through Neolithic sites, this Canadian historian jetted off to Orkney, Scotland for a vacation. Orkney and Canada share a strong historic connection since the Hudson’s Bay Company hired a great many of their labourers from Orkney. Working with fur trade history made me aware of this, but the only concession my trip plan made to the Orkney-Canada connection was an as-of-yet unread copy of Patricia McCormack’s paper, “Lost Women: Native Wives in Orkney and Lewis” tucked into my suitcase.

After three flights, I arrived bleary-eyed on the largest island of this archipelago north of the Scottish mainland, feeling as though I had travelled to a rather remote part of the world. I couldn’t have been more wrong. Orkney may feel isolated today, but when the Atlantic was bridged with boats instead of planes flying out of densely populated southern urban centres, Orkney was much more central.

Maps of the world on display in Orkney did not have the equator as the centre of the image. Rather, they tilted the globe northward, bringing into focus areas of the northern Atlantic which usually shrink into obscurity- including Orkney itself. By changing the angle from which I considered the globe, I was able to see connections that had never before been made clear to me. One of those connections bridged the wide watery expanse between Orkney and western Canada.

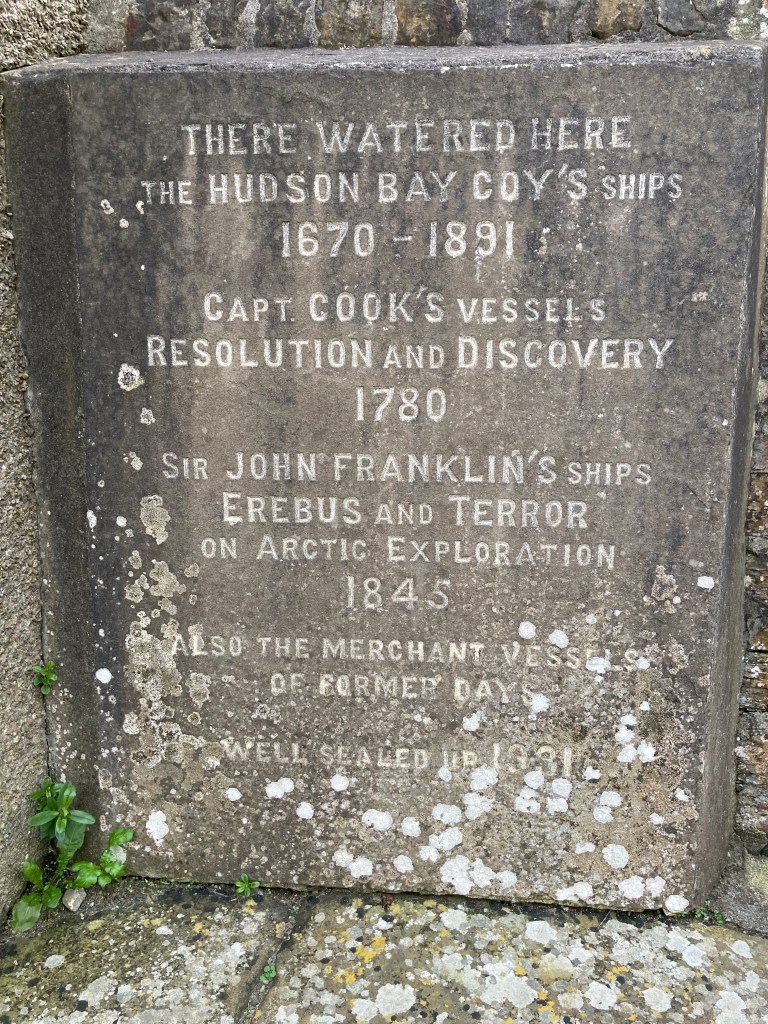

Orkney’s northerly latitude made it a geographically convenient place for the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). The oceanic entrance to the Hudson Bay is substantially further north than the mouth of the St. Lawrence seaway, which means that starting the journey from Orkney makes far more sense than leaving from a “more central” port in southern England. Hudson Bay-bound ships “called in” (made a stop at) at the Stromness harbour on the western edge of Orkney as their last landing place before braving the Atlantic crossing. Once in this harbour, they visited Login’s Well (pronounced “Logan’s”) to fill their all-important supplies of drinking water.

But it wasn’t just Orkney’s fresh water the HBC wanted. Orkney’s men were also in high demand.

As Peter Melnycky, historian and editor of Opponents and Neighbours: Fort George and Buckingham House and the Early Fur Trade on the North Saskatchewan River, 1792 to 1800 explains,“By 1800 nearly eighty percent of all HBC employees were Orkneymen, while most of the rest were English. As the last landfall for HBC supply ships before they crossed the North Atlantic for Hudson Bay, Orkney was a convenient location for recruitment and company officials believed the climate, economy and culture of Orkney made its residents ideal employees. Orkneymen were reputed to be sober, industrious, hardy, conscientious, frugal, and uncorrupted by the vices that afflicted some HBC employees from London, for example.”

Today part of Alberta’s Fort George & Buckingham House Provincial Historic Site, the HBC’s fur trading post (called Buckingham House) was one of the earliest posts inland from the Hudson Bay. Though 80 per cent of HBC employees in general were from Orkney, the percentage of Orcadians at Buckingham House was even higher. In 1792, Orcadians represented a mere 89 per cent of the HBC employees, and in 1796, 97 per cent of the employees were from Orkney.

A perfunctory flip through binders at the Stromness Museum revealed names of a great many Buckingham House men. Back in Canada, the places of origin listed on the Buckingham House employee roster read like a tour of Orkney with geographical names like Stromness, Firth, Evie, South Ronaldsay, Sandwick, Orphir, Harray, Birsay, Burray and so on.

Despite the many places from which the Orcadians working at Buckingham House originally hailed, they would still have shared many connections which would undoubtedly have affected the fort’s working atmosphere. Melnycky writes, “Distinctions of rank among the twenty-eight Orcadians [present at Buckingham House in 1796] were muted by their shared Orkney heritage, which probably included friendship and kinship ties that originated on the islands. The two Daveys and the two Fletts from Firth, the two Isbesters from Harray, the two Mowatts from Burray, and George and Magnus Spence from Birsay could have been related. If not related, they almost certainly would have known each other given the tiny populations of those island communities. The eight men from the island of Burray would have grown up together. Surrounded by numerous Indigenous peoples, and other employees from the Canadas and England in the northwest, their sense of being a distinctive group would have been strongly reinforced. Regardless of rank, they shared the same cramped “cabin” accommodation and the same meals prepared in the cook tent. News from Orkney in letters and newspapers would have been shared as well.”

Orcadians were widely literate, a product of a robust school system on the islands. Unlike most North West Company employees, who could neither read nor write, the Orcadians working for the HBC were able to stay in touch with family and friends at home through letters and newspapers. Those with the means not infrequently sent their sons back to Orkney to receive a strong education in the hopes that it would improve their chances in life. Orcadians’ literacy also provides historians with opportunities to understand the lives of these working men through the letters sent back and forth across the Atlantic.

What motivated so many Orkneymen to sign with the HBC? Often, the purpose was simply to earn enough money to buy some land back in Orkney when their term was over. HBC servants were often able to save 70 per cent of their wages. Indeed, the amount of money some men were able to bring home resulted in their being known as “peerie lairds” (peerie is an Orkney dialect word meaning small). Some of the Orcadians who laboured in the woods and on the rivers across the Atlantic returned home to mostly treeless, ocean-salted Orkney, and a few even returned with their Indigenous wives, as I learned from McCormack’s article, “Lost Women.” Others stayed in Canada for the rest of their lives becoming integrated in local Indigenous groups and learning a variety of Indigenous languages. The legacies of those who stayed in Canada is fascinating and would require far more words than this blog post allows me.

Family names I’m familiar with from fur trade records appeared all over Orkney. Even the directions a helpful Stromness resident gave me referenced “Wishart’s Hardware Store.” So, I walked down the street, marking my location as I passed names like Flett, Linklater, Spence, Sinclair, and Gaddy engraved on plaques and stones, in newspapers and windows until I found Wishart’s Hardware Store.

When Orkneymen came to Canada, they also brought food, culinary preferences and boating technology. The Buckingham House journals tell us that cabbage seeds brought from Orkney were being planted in the fort’s garden in May of 1794, and that the men were upset when their supply of oatmeal from home was threatened. The food crossovers continued during my trip as I was greeted with a, “peerie bere Bannock” (small barley Bannock) for breakfast each morning at my bed and breakfast.

Orkneymen were also popular recruits for the HBC partly because they known to have skill with boats. A common description of Orcadians is to say they were, “farmers with boats.” Despite their skill with ocean-going fishing vessels, they did have to learn new skills to pilot canoes down Canadian rivers. Their previous experience didn’t go to waste, however. York boats, those large boats with significant cargo capacity that helped the HBC gain an advantage over their rivals, were based on Orkney fishing boats. York boats were, “a distinctive Orkney contribution to the fur trade.”

It was somewhat startling to walk into the Stromness Museum and come face to face with objects I recognize from most museums and historic sites across western Canada: point blankets, beaver pelts, metal leg-hold traps, flint and steel and copper kettles. I was also delighted by a collection of beautiful Indigenous artwork, with labels that named the artist whenever possible, and explained the connection between these Indigenous items and the people of Orkney. The gift shop even had a small book telling about an Orcadian woman who came to Canada to find her cousins separated by 200 years. The effort put into highlighting the voices, stories and experiences of First Nations people was evident, and it is clear that school students are learning about the importance of relationships between First Nations people and Orcadians during the fur trade. A board game produced by local school children even awarded the player points if they took the advice of local Indigenous peoples and took away points from those who ignored local advice.

When one reflects on such high numbers of Orcadians working in the fur trade, it is hardly surprising that the apparently automatic Orkney response to learning I was Canadian was to exclaim, “The Hudson’s Bay Company!” Clearly the impact of such extensive recruitment in Orkney left a lingering impression on Orcadians.

Just days before I was to re-cross the Atlantic on my way home, I was walking along the ocean and came across a piece of birchbark which had washed up on the Shetland beach (just north of Orkney). This piece of tree had travelled a long way from Turtle Island. Perhaps it was a reminder of the ways that oceans can link apparently distant places.

Sources

Babcock, Douglas and Michael Payne. Edited by Peter Melnycky. Opponents and Neighbours: Fort George and Buckingham House and the Early Fur Trade on the North Saskatchewan River, 1792 to 1800. Alberta Culture, Multiculturalism and Status of Women with The Friends of the Forts- Fort George and Buckingham House Society. 2020.

Gange, David. Frayed Atlantic Edge: A Historian’s Journey from Shetland to the Channel. William Collins, 2019.

McCormack, Patricia. “Lost Women: Native Wives in Orkney and Lewis.” In Recollecting: Lives of Aboriginal Women of the Canadian Northwest and Borderlands. Eds Sarah Carter and Patricia McCormack. Athabasca University Press, 2011.

Twatt, Kim. Full Circle: An Orkney Family Reunited After 200 Years Separated by Distance and Culture. Herald Publications, Kirkwall, 2007.

Thank you for this article, Suzanna. You’ve given people with an interest in the western Canadian fur trading era a gift by going to and then teaching us about the place where so many of the HBC employees were from.

was looking forward to seeing objects that -1-“are a reminder of their Cree ancestry.”

2- “a connection with Western Canada with the Orkney Islands. “

3-“and a connection with the early 19 century”

you provide a photograph of a beaded watch holder which is

1-not Cree

2-connects not at all with “Western Canada”

3-has no connection with the “early 19th century.”

It is an 1890’s Mohawk , piece of commercial beadwork sold as a cheap souvenir at Niagara Falls .

Most appropriately designated as”junk”.