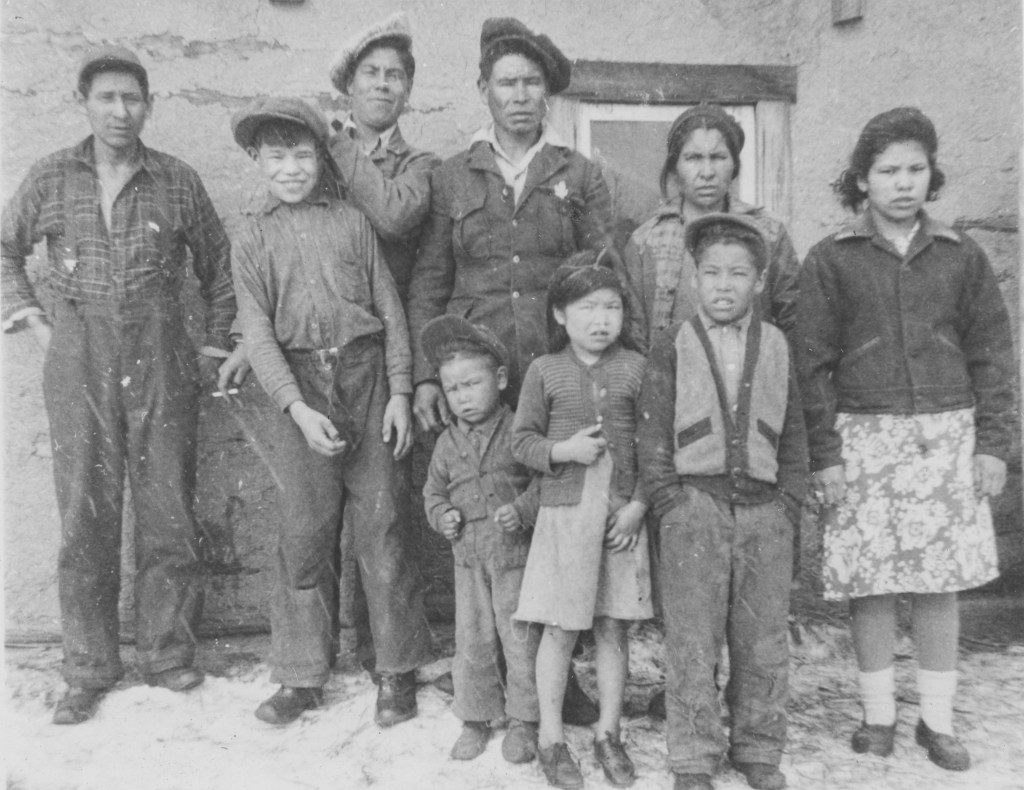

Editor’s note: The banner image above, of Sapaces (seated fifth from left) and family at the Athabasca Bridge opening ceremonies in 1952, is courtesy of the Athabasca Archives.

Written by: Darren DeCoine, Bigstone Cree Nation and Laura Golebiowski, Indigenous Consultation Adviser

Historic trails crisscross much what is now known as Alberta. They serve as reminders of past occupation and travel and, in the case of Bigstone Cree Nation, continue to be used to access sites and landscapes significant to Indigenous Peoples. This is the story of one historic trail, known locally today as Sapaces Gambler Okayas Meskanas: the Jean Baptiste Gambler Historic Trail.

The Matchemuttaw and Gambler families signed Treaty as part of the Peeayseas First Nation near Lac La Biche. They travelled northwest and established themselves in the Kito Sakahikan (Calling Lake) area by 1875, and transferred to the Bigstone Band in 1911. By 1915, patriarch Sapaces (colonial name Jean Baptiste Gambler) had built a house, storehouse and stable along the north shoreline of Kito Sakahikan, and was advocating for reserve lands to government representatives.

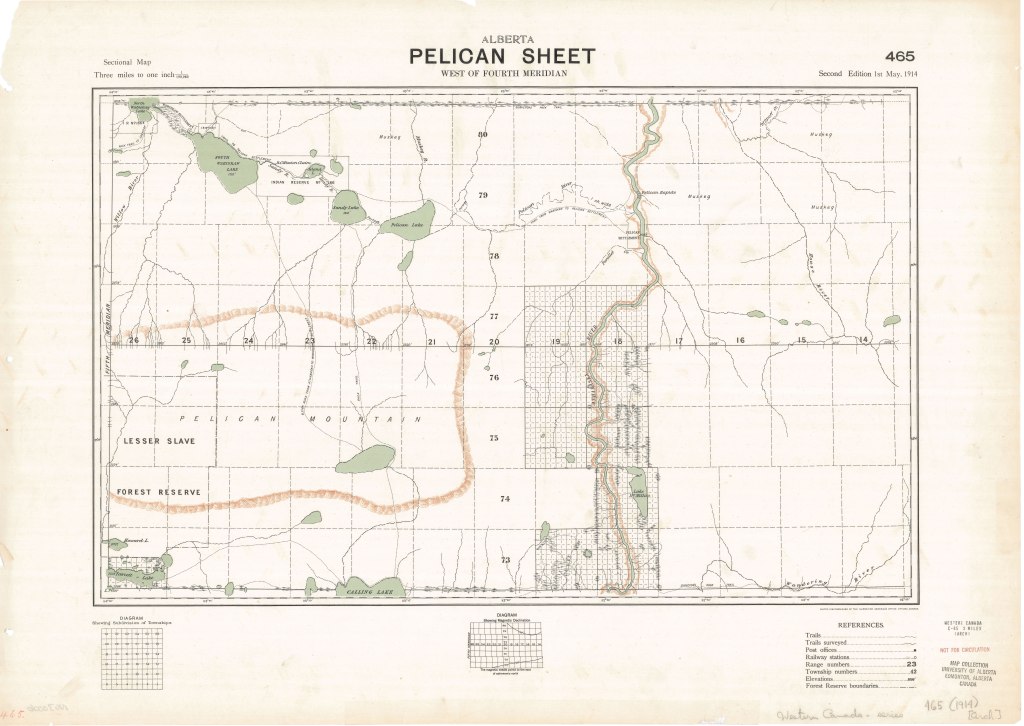

In the early 1900s, a trail extended between Kito Sakahikan and Wapaskow (Wabasca), connecting the families and communities contemporarily comprising Bigstone Cree Nation. In 1914, the route was identified as a “pack trail” on the Pelican District sectional map; a parallel trail to the west was the, “sleigh road from Athabaska to Wabiskaw Settlement.” Sapaces and his descendants travelled the region on these trails for generations.

The trail likely saw the most use in the 1940s, when it was travelled by horse and wagon in the summer and dog team in the winter. For several decades, this was the only route between Kito Sakahikan and Wapaskow. The broader trail network extended south to Manto Sakahikan (Lac Ste Anne) and branched westward toward Kamiscikosik Sakahikan (Orloff Lakes) and Moswa Kaskewekanow (Moose Portage) along the Athabasca River. Portions of the trail, and areas adjacent to it, were developed for motorized access as a winter road. The winter road was made to support heavy trucks that were hauling logs and equipment north. It is assumed the winter road fell to disuse after 1989, when the Highway 754 was constructed.

In Sapaces’ time, the trip from Kito Sakahikan to Wapaskow could take three or four days by dog or horse team; however, not everyone was in a rush to reach their destination. Along the trail, people camped, harvested medicines and berries, hunted and fished.

Mistakwapiskaw Sakahikan, or Rock Island Lake, made for an ideal stopping place along the historic trail. Families traveling Sapaces Gambler Okayas Meskanas would spend several days at the lake to prepare for their longer journeys. Those travelling south to Manto Sakahikan—a month-long journey—would spend a significant amount of time gathering the necessary food, drying meat and fish and preparing supplies. To this day, berries and medicines can be found along the lakeshore and river outflow.

A variety of wildlife, including lynx, wolf, caribou, rabbit and grouse can be observed along the historic trail. In the 1920s, trappers brought their furs to the south shore of Rock Island Lake to trade with Nick and Rose Tanasiuk, Ukrainian settlers who moved to the region from Pakan in 1919 and lived at Rock Island Lake until 1946. Today, the majority of the trail falls within Registered Fur Management Area no. 183, a community-held trapline accessible to all Bigstone Cree Nation members with the appropriate trapper licence.

Mistakwapiskaw Sakahikan also sustained those who lived here permanently, including the Gambler family. Elder Jack Gambler, the grandson of Sapaces, was born on the shores of Mistakwapiskaw Sakahikanto parents Johnny and Agnes (née Beaver). The Gamblers had a homestead just south of the outflow, which in 2010 may have been referenced as: “the old house on the old Sandy Lake Road, no longer standing, just foundations.”

Jack Gambler loves the bush. He grew up outdoors and would much rather spend time there than indoors. It is quiet in the bush, which affords him with peace of mind. Jack says if you’re ever facing uncertainty, go into the bush—you will know what to do afterward.

As a child, Jack hunted with his father and began trapping when he was nine years old. He travelled Sapaces Gambler Okayas Meskanas with his father when he was 13 years old; it took two days by wagon to reach Ekowiskak Sakahikan (Sandy Lake) from Kito Sakahikan.

In February 2020 and again in November 2023, Jack, along with Darren DeCoine and Laura Golebiowski travelled Sapaces Gambler Okayas Meskanas, documenting the linear extent for protection under the Historical Resources Act. Along the trail we encountered historic cabins, campsites, plant harvesting sites and ceremonial locations. Late last year, historic interpretive signage was installed at both Sapaces Gambler Okayas Meskanas and Mistakwapiskaw Sakahikan, raising awareness for the important histories of these landscapes and encouraging respectful visitation.

In addition to Sapaces Gambler Okayas Meskanas and Mistakwapiskaw Sakahikan, interpretive signage will be installed at six more significant cultural locations within Bigstone Cree Nation’s territory this year. Each location has been afforded protection under the Historical Resources Act through collaboration between the Nation and the Historic Resources Management Branch’s Indigenous Heritage Section. The initiative was funded by the Indigenous Reconciliation Initiative – Cultural Stream.

The protection and promotion of Bigstone Cree Nation’s cultural heritage helps to ensure these special places can continue to be known and used, and that Nation members and non-Indigenous peoples alike can participate in and celebrate these histories.

Thank you to Jack Gambler for sharing his knowledge and family’s stories, and to Darren DeCoine for his facilitation and long-time partnership with the Indigenous Heritage Section. Hiy hiy!

Sources

Fedirchuk McCullough and Associates Ltd. (1983). Historical Resources Impact Assessment: Alberta Transportation Secondary Road 813 Extension (ASA Permit 82-134C). Prepared for Archaeological Survey of Alberta.

Indian Claims Commission. (2000). Bigstone Cree Nation Inquiry Treaty Land Entitlement Claim. Retrieved online from https://iportal.usask.ca/docs/ICC/BigstoneEng.pdf.