What makes your holiday season complete? Is it fruit cake, latkes or bannock? Lighting a menorah, Christmas tree or a kinara? How old or new are the traditions you participate in? Where did they originate?

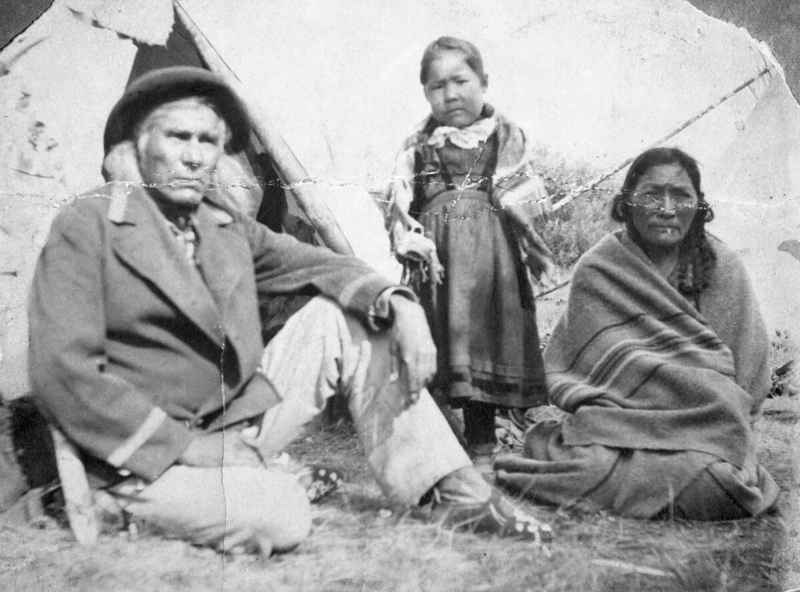

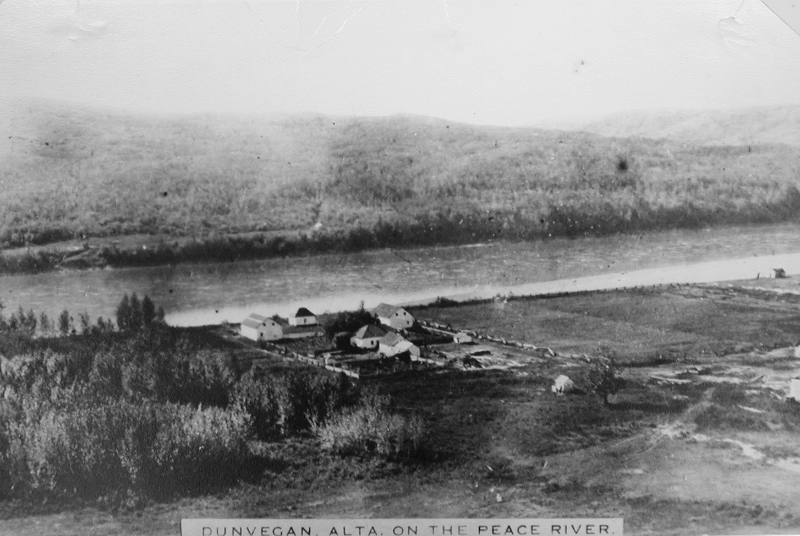

The Beaver people who first inhabited the areas bordering the Peace River have been gathering at Dunvegan for thousands of years. Like other Indigenous peoples, before the arrival of the fur traders and missionaries, it’s possible they may have celebrated the Winter Solstice while camping in the area.

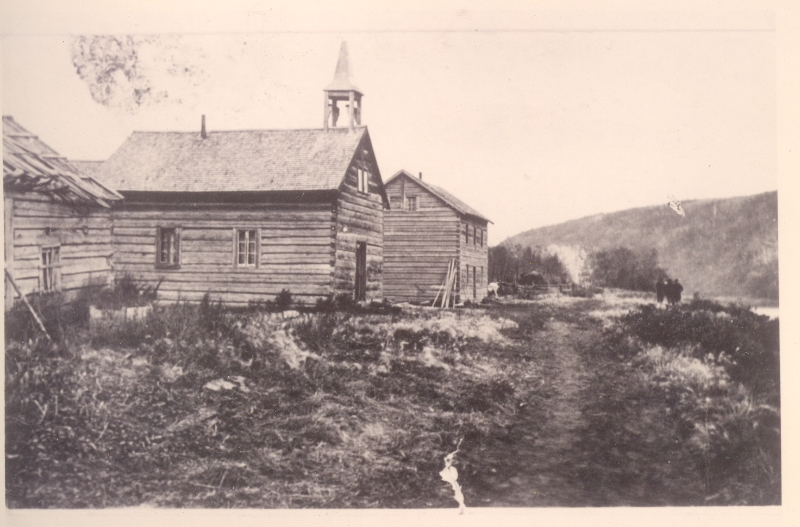

When Northwest Company fur traders arrived in 1805 and established Fort Dunvegan, they brought with them the customs of European Christians, particularly those of the Scots. You’ve probably heard of Kwanzaa, but have you ever heard of Hogmanay? In Scotland, Christmas was celebrated quietly, while Hogmanay or New Year’s Eve, was well…a party! Being as many fur traders originally hailed from Scotland, those traditions came with them over to what is now known as Canada.

Indeed, this is reflected in the journals left by the men in charge at Fort Dunvegan through the 1800s. In some cases, Christmas isn’t even mentioned at all on December 25. When it is mentioned it’s often to say that nothing of importance happened. But every entry that was made on January 1 (at least between 1822 and 1844) mentions everyone gathering at the fort for their usual treat of a ration from the store. This included gifts of tobacco, rum, meat or biscuits. Even lime juice has been mentioned as a special treat given to visitors.

Read more