Written by: Todd Kristensen, Archaeological Survey of Alberta and Jack W. Brink, Royal Alberta Museum

The Archaeological Survey of Alberta is proud to release the complete volume of Occasional Paper Series No. 40, available for free download:

Archaeological discoveries and syntheses in Western Canada: the Occasional Paper Series in 2020

In addition to two articles published earlier this year, this blog announces the release of four new articles to complete the volume:

Microblades in northwest North America

Skilled flintknapper Eugene Gryba discusses a specific stone tool technology called microblades in northwest North America. He draws on decades of first-hand experience creating stone tools to argue for a free-hand pressure technique to explain archaeological occurrences of microblades across the continent.

Napi effigies

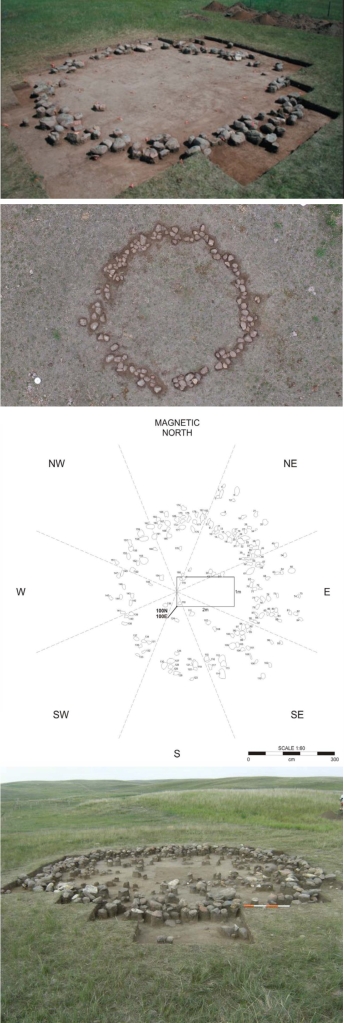

Trevor Peck presents an updated synthesis of unusual and intriguing archaeological features called petroforms (boulder outlines), in this case, Napi effigies on the Plains. These large arrangements of boulders depict an important Siksikaitsitapi (Blackfoot) entity who figures prominently in stories and belief systems. The paper discusses their style and distribution and argues for a subdivision of different groups of Napi effigies that may be linked to different phases of Siksikaitsitapi history.

Porcellanite

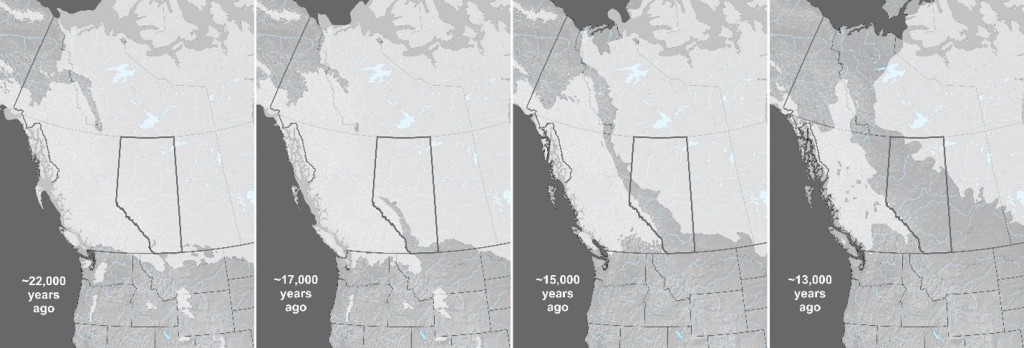

A team of archaeologists is studying the raw materials used in Alberta to make stone tools over the past 12,000 years. The fifth paper in the current volume discusses a material called porcellanite that was fused over millions of years through natural coal combustion. Indigenous people used porcellanite from Montana, North Dakota, and from local outcrops in Alberta to make stone tools. The paper presents photographs and several laboratory results to help archaeologists accurately identify porcellanite.

Surface collection of artifacts

The final paper in the volume presents an interesting surface collection of artifacts from northern Alberta. The collection from the Fort Vermilion area includes stone projectile points, scrapers, knives, cores, and flakes made out of a variety of raw materials. Heinz Pyszczyk and colleagues from the Royal Alberta Museum and the University of Lethbridge argue that tool styles and affinities to the south suggest that the collection represents 9000 years of human occupation in the region.

Previous volumes can be downloaded for free here. Thank you to all the authors. If you are an archaeologist interested in contributing to the 2021 issue, dedicated to heritage in Canada’s boreal forest, please contact the Archaeological Survey of Alberta.