Written by: Todd Kristensen and Emily Moffat, Archaeological Survey of Alberta

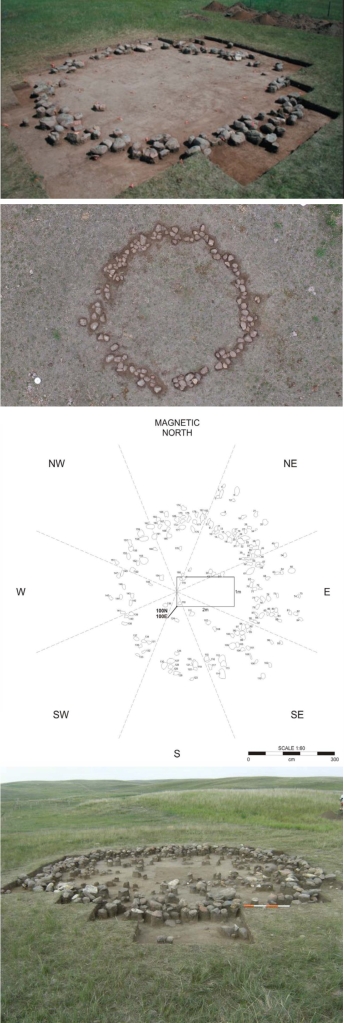

Small rings of rock appear across Alberta’s prairies. These stones once weighed down the bison hide covering of tipis – a type of dwelling used by generations of First Nations. Tipis, and the remnants of them, have drawn the attention of archaeologists and historians in the province for over 70 years. It is estimated that Alberta had a million stone circles before being displaced by farming and other developments. Currently, the province has over 8,000 recorded archaeological sites with tipi rings: some are a single circle (a small camp) while others host over 200 rings in one spot (a large gathering of family and allies). New figures and imagery here highlight decades of archaeological research and help visualize how records of tipi rings can reveal dimensions of pre-contact life.

A tipi is a hide or fabric cone supported by wood poles. At first glance, tipis look symmetrical but most are designed to be tilted towards the back. The steep side usually faces oncoming winds and the shallower, more sheltered side has a door opening and smoke hole. In Alberta, the door often faces East to the rising sun. Smoke from a central fire escapes directly upwards through a hole with adjustable flaps on either side: a characteristic feature of Plains tipis. In cold, windy places, like in Alberta, tipis often have an inner liner for extra warmth and are tethered by rope from the pole junction down to a central peg for added stability. Thankfully for archaeologists, many tipis were anchored by circles of stones around the perimeter. By measuring these round remnants, archaeologists can learn how many people likely lived at a site and what types of relationships they had with surrounding animals, both wild and domestic.

A number of mathematical minds have explored tipi rings. A well-known study in 1988 noted that the average tipi ring in Alberta is about 4.6 m (15 feet) in diameter. The smallest rings that anchored tipis are 2.3 m (7 ½ feet) while the largest were just shy of 9 m (about 28 feet). What does that mean for living space?

Smaller tipis are comfortable for two or three people while larger ones could host 30 or more for social gatherings. People dismantled tipis and moved camps up to 30 times a year on the plains, which meant that ease of construction and transport were priorities. For the latter, oral histories suggest that each family had upwards of ten dogs. These pets likely played a role more akin to modern wheelbarrows than the companion role of our canines today. Dogs were loaded with a type of pack saddle or travois (wooden poles that held bundles). Aside from tipi poles, what did dogs transport?

Bison hides were carefully tanned and stitched together to make covers and liners. The average tipi in pre-contact Alberta needed about 24 bison hides. The largest dwellings required almost 60 bison to complete and these hides needed to be replaced every year or two. In addition to hides, tipis required cordage and wooden lacing pins. The stones used to anchor the base would have been acquired on-site, as opposed to loading them on to the backs of dogs. Sometimes, old tipi rings were re-used by different groups at a site. When combined, the materials for one average-sized tipi would have weighed about 220 kg (485 lbs). Rufus to the rescue!

Researchers have used floor surface areas of tipis to understand how many people lived inside. Their geometry is supported by Indigenous accounts. The average tipi would have been home to eight or nine people. That family unit needed at least six dogs (based on a limit of 34 kg or 75 lbs per travois) just for tipi materials. Additional dogs hauled personal belongings, tools, clothing, food and other supplies.

The outcome is a story of ecology and camp dynamics that all stems from rings of prairie stones. Archaeologists can move from tipi rings to thinking about how often and why bison were hunted, how big camps were, how many dogs were there and the collective number of mouths to feed. In a thesis from the University of Alberta, Reilly (2015) calculated that a tipi ring site, called Ross Glen at the edge of Medicine Hat in southern Alberta, had around 100 people with tipis that required an enormous 620 hides to make and over 150 dogs to move. Tipi hide requirements might just have outstripped meat requirements for people living in them. This means that a major motivation for large-scale bison hunting at big sites like Head-Smashed-In-Buffalo-Jump could very well have been hide production.

University of Calgary archaeologist Gerald Oetelaar developed a number of ways to think about space division within a tipi. His ideas are informed by Indigenous oral histories, ethnographic records and basic principles such as how fire illuminates dwellings and how human movement within a tipi would have affected objects on the ground. Archaeologists across North America have applied his diagrams to interpret tipi floor distribution of food scraps (bone), objects related to maintenance (stone flakes and tools) and features (spaces for bedding, hearths and ceremonial altars).

Lastly, historic photographs of tipi camps in Alberta have been colourized with photo-editing software to breathe life into them. Colourizing images helps humanize the past and alerts the eye to previously overlooked components of tipi life. This can include subtle but interesting aspects like the ages of tipi covers: new tipis are a clean, light brown while the tops of older ones are stained by smoke. On a larger scale, colour enlivens the past and reminds us that it was as dynamic as life today: it can help the viewer place themselves in a landscape to identify with the scene and its occupants. This is one of the principles that motivated the current tipi visualizations and a broader project called the Heritage Art Series.

The goal of the Heritage Art Series is to use modern art and supporting images as portals to tell interesting stories about Alberta’s past. This hopefully in turn encourages respect and preservation. The image below was painted by Piikani artist Rebekah Brackett in 2018 as part of the series. Titled “This Woman’s Work”, the art depicts the toil, immense value and beauty of tanning hides on the prairies. Readers can explore more art-anchored stories here including tales of Alberta’s gold rush, an interwoven history of ammonites, an ancient flood that exposed the oil sands or a brief history of fishing in Alberta’s northern forests.

Sources further reading

Brumley, John H., and Barry J. Dau. 1988. Historical resource investigations within the Forty Mile Coulee Reservoir. Manuscript Series 13. Archaeological Survey of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta.

Ewers, John C. 1955. The horse in Blackfoot Indian culture: With comparative material from other western tribes. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Finnigan, James T. 1982. Tipi rings and plains prehistory: An assessment of their archaeological potential. Mercury Series 108. National Museum of Man, Archaeological Survey of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario.

Kehoe, Thomas F. 1960. Stone tipi rings in north-central Montana and the adjacent portion of Alberta, Canada: Their historical, ethnological and archaeological aspects. Anthropological Papers 62. Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Oetelaar, Gerald A. 2000. Beyond activity areas: Structure and symbolism in the organization and use of space inside tipis. Plains Anthropologist 45(171):35-61.

Reilly, Aileen. 2015. Women’s work, tools, and expertise: Hide tanning and the archaeological record. MA thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta.

Wissler, Clark. 1910. Material culture of the Blackfoot Indians. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 5. New York.

Very interesting!