Editor’s note: The research presented in this blog is from a published journal paper co-authored by Timothy Allan, John Ives, Robin Woywitka, Gabriel Yanicki, Jeffrey Rasic and Todd Kristensen.

Ice sheet margins derived from: Dalton, A. S., M. Margold, C. R. Stokes, L. Tarasov, A. S. Dyke, R. S. Adams, S. Allard, et al. 2020. An Updated Radiocarbon-Based Ice Margin Chronology for the Last Deglaciation of the North American Ice Sheet Complex. Quaternary Science Reviews 234: 106223–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106223.

Written by: Todd Kristensen, Archaeological Survey of Alberta

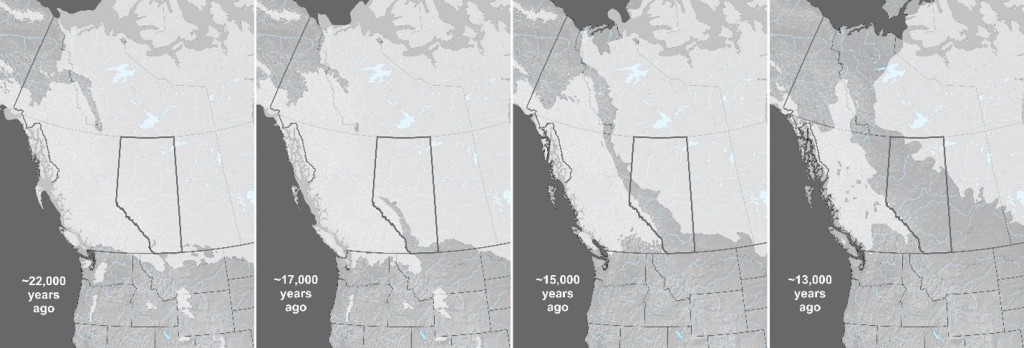

Alberta was once covered with glacial ice. Around 22,000 years ago, portions of the ice that sprawled across the province were over 1.5 kms thick. When the ice began to melt, it retreated in two directions (northeast and west) and exposed a pathway dubbed the Ice-Free Corridor that crossed through Alberta and connected previously exposed land masses over the warmer United States and a colder but drier region to the north called Beringia (parts of Northwest Territories, Yukon, Alaska, and Russia). People had settled into the corridor in what is now Alberta by 13,000 years ago. Where did they come from?

New archaeological discoveries are pushing back the ages of when people arrived in Beringia and to the south in the United States. To help understand which of those two areas are the likely source of people who came to Alberta, archaeologists have recently looked at the tools they were carrying, specifically, what kinds of stone the tools were made of. Some of the rock types that people used to craft things like spear points, scrapers and knives, are only found in certain areas in North America: their presence in Alberta’s archaeological record indicates that the stones were transported from far away. In turn, archaeologists look at changes in those ‘toolstone’ materials to track changing relationships; in the absence of other things that don’t preserve in Alberta’s soil, stone tools reveal where people migrated from, who they were interacting with (their ‘kin’) and how that all changed over thousands of years.

A rock type called obsidian has proven scientifically valuable because it comes from volcanoes and often has a specific and local geochemistry that archaeologists can analyse with laboratory equipment. Volcanoes in Alaska and Yukon as well as Idaho and Wyoming produced obsidian that is near the northern and southern openings of the Ice-Free Corridor. People could have potentially picked up these obsidians on their way to recently exposed landscapes in Alberta (the province lacks any natural outcrops of obsidian). They also may have exchanged obsidian with their family or other trade partners after settling into new home territories across Alberta. A research team from the Canadian Museum of History, MacEwan and the U of A (Edmonton), the US National Park Service (Alaska), and an archaeology company in Edmonton looked at Alberta’s oldest obsidian artifacts in the hopes of finding where the earliest people came from and who they maintained relationships with.

The results of recent archaeological work point south. Most of the earliest artifacts were geochemically matched to volcanic outcrops in Idaho and Wyoming. Surprisingly, one of the oldest obsidian spear points (from the Grande Prairie area) matched a volcano in Oregon. This indicates a kinship or exchange relationship from about 12,500 years ago that spanned over 1,300 kilometres and connected northwest Alberta to the Pacific Northwest and Intermountain areas of the United States. It seems that people spilled into the Ice-Free Corridor from the south and kept moving north as the corridor widened. Even more surprising was the hint of a northern influence among the earliest people. A spear point that is potentially 12,000 years old (from the Manning area) matched an obsidian source in interior Alaska. So, while the signal of early people in the province is dominated by a southern influence, traces of northern people from Beringia appear in northwest Alberta suggesting a retained kinship or exchange network that spanned well over a whopping 2,000 kilometres.

Archaeologists think that southern people steadily poured north but occasionally met strangers from Beringia as both groups adapted to recently exposed and ice-free places. Laboratory work has teased out human relationships from stone tools. The first people who settled new landscapes preserved immense networks along which likely moved ideas, goods, language and DNA back and forth from the Pacific Northwest through Alberta to Beringia.