Editor’s note: The research presented in this blog is from a published journal paper co-authored by Timothy Allan, John Ives, Robin Woywitka, Gabriel Yanicki, Jeffrey Rasic and Todd Kristensen.

Ice sheet margins derived from: Dalton, A. S., M. Margold, C. R. Stokes, L. Tarasov, A. S. Dyke, R. S. Adams, S. Allard, et al. 2020. An Updated Radiocarbon-Based Ice Margin Chronology for the Last Deglaciation of the North American Ice Sheet Complex. Quaternary Science Reviews 234: 106223–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106223.

Written by: Todd Kristensen, Archaeological Survey of Alberta

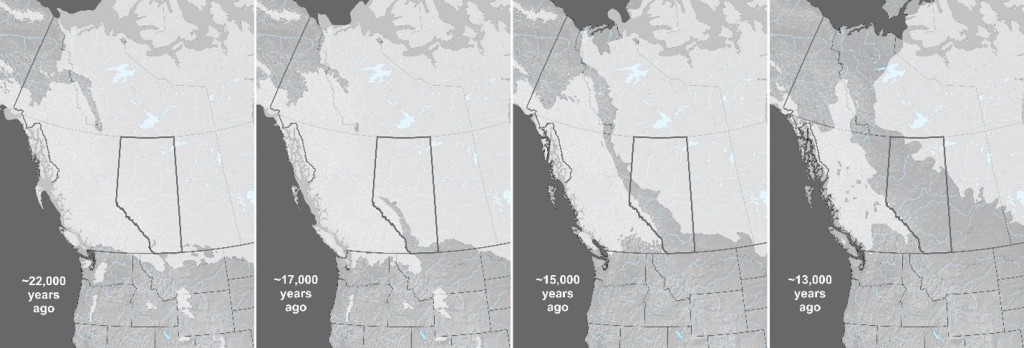

Alberta was once covered with glacial ice. Around 22,000 years ago, portions of the ice that sprawled across the province were over 1.5 kms thick. When the ice began to melt, it retreated in two directions (northeast and west) and exposed a pathway dubbed the Ice-Free Corridor that crossed through Alberta and connected previously exposed land masses over the warmer United States and a colder but drier region to the north called Beringia (parts of Northwest Territories, Yukon, Alaska, and Russia). People had settled into the corridor in what is now Alberta by 13,000 years ago. Where did they come from?

New archaeological discoveries are pushing back the ages of when people arrived in Beringia and to the south in the United States. To help understand which of those two areas are the likely source of people who came to Alberta, archaeologists have recently looked at the tools they were carrying, specifically, what kinds of stone the tools were made of. Some of the rock types that people used to craft things like spear points, scrapers and knives, are only found in certain areas in North America: their presence in Alberta’s archaeological record indicates that the stones were transported from far away. In turn, archaeologists look at changes in those ‘toolstone’ materials to track changing relationships; in the absence of other things that don’t preserve in Alberta’s soil, stone tools reveal where people migrated from, who they were interacting with (their ‘kin’) and how that all changed over thousands of years.

Read more