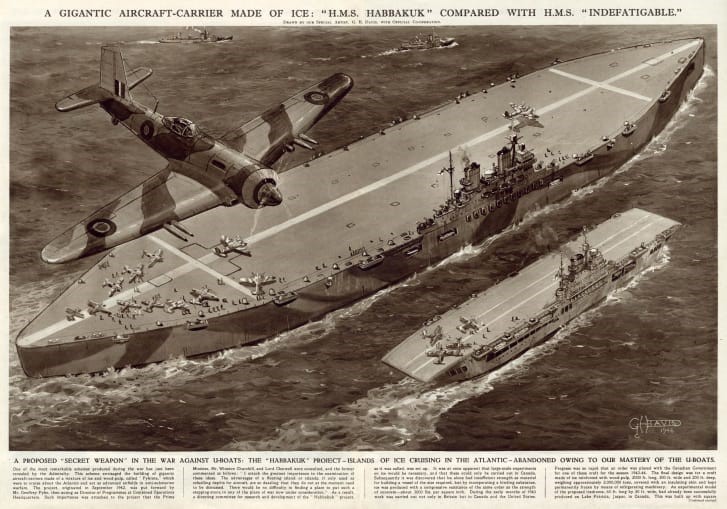

Editor’s note: The banner image above is courtesy of the Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary

Written by: Sara Bohuch, BA Archaeology (Simon Fraser University) , MSc Conservation Practice (Cardiff University)

At the turn of the 20th century, the government of Canada continued to look for ways to convince people to move to the country and transform the land there into profitable resources. The government tried many different strategies to achieve this over the years, and some of the more successful tactics were old-fashioned advertising campaigns. Polished ads were produced that depicted Canada (and the prairies within it) as the best sort of fresh start, with bountiful potential and the opportunity to forge your own community.

However, for many prospective immigrants, Canada was not exactly the landscape as advertised. It was not a vast empty expanse rich with resources, as many of the campaigns described. It seemed that the numerous harsh realities of making a living on the prairies were quietly glossed over by the various advertisements.

So how do you sell the Prairies in particular, over other parts of Canada?

In the early 1800’s the propaganda campaign of the “Glorious Canadian West” was accompanied by artwork and slogans depicting bustling communities and vast farmland. During the latter half of the century, the invention of the camera upgraded the medium of the message, though the imagery stayed similar. The new technology offered a way to capture the “truth” of a place and was able to communicate that truth to an increasingly wider audience quickly.

One of the most well-known providers of such promotional material for the government was the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). The CPR began to use photography to document the Canadian landscape in the late 1880s and continued with its usage well into the 20th century. They used the images captured by their photographers to promote not only a certain image of the country, but also their own operations within Canada.

In the Glenbow’s Archives and Special Collections there is a series of these types of photographs, dating from the 1900s and documenting the landscape around the Albertan line. Even knowing the history and reason that these photos were taken in the first place, it is still undeniable that these early photographers were very good at what they did. The images that were captured showcased an Albertan landscape bursting with natural beauty and bountiful acres of farmland.

All images courtesy of the Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary.

Click the link below to view the gallery.

Read more →