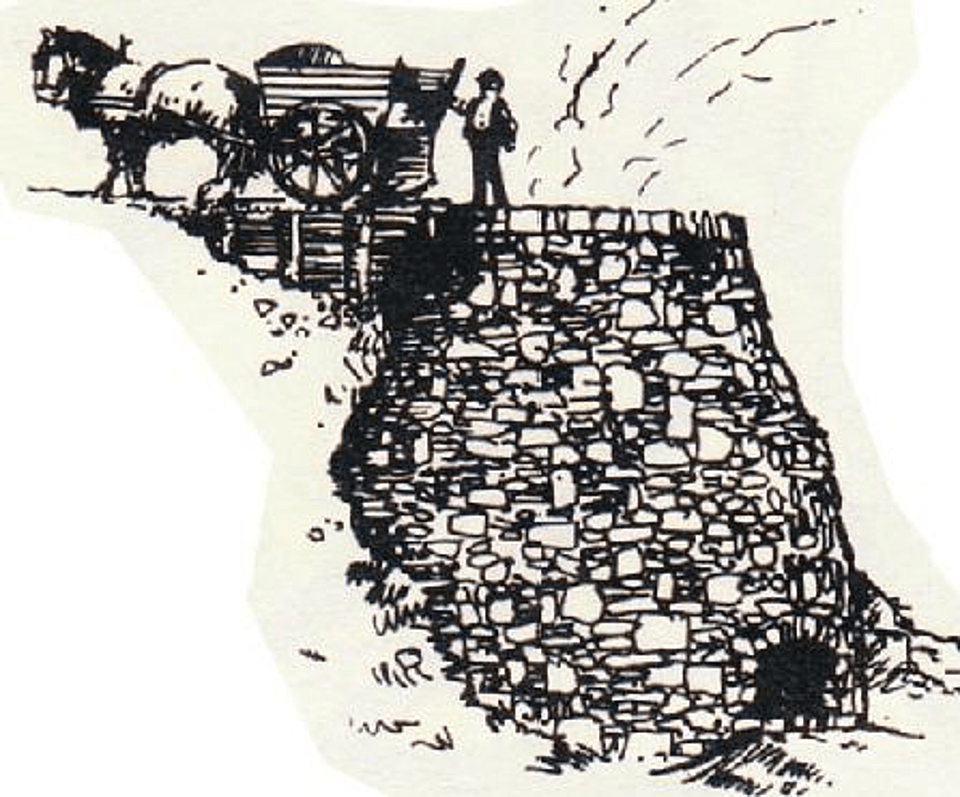

Editor’s note: All images in this post were taken by Suzanna Wagner. The image above is of a view across the Stromness Harbour, Orkney.

Written by: Suzanna Wagner, Program Coordinator, Victoria Settlement and Fort George & Buckingham House

Have you ever travelled vast distances only to find pieces of home?

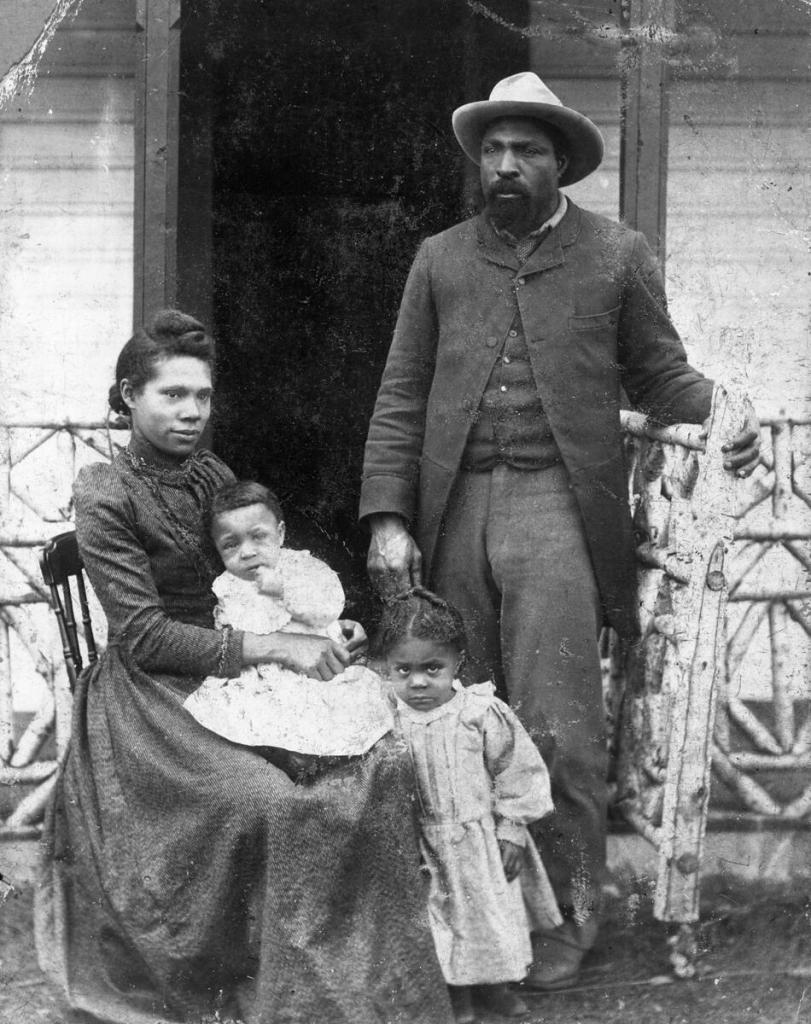

Intent on exploring new vistas, seeing the ocean, and walking through Neolithic sites, this Canadian historian jetted off to Orkney, Scotland for a vacation. Orkney and Canada share a strong historic connection since the Hudson’s Bay Company hired a great many of their labourers from Orkney. Working with fur trade history made me aware of this, but the only concession my trip plan made to the Orkney-Canada connection was an as-of-yet unread copy of Patricia McCormack’s paper, “Lost Women: Native Wives in Orkney and Lewis” tucked into my suitcase.

After three flights, I arrived bleary-eyed on the largest island of this archipelago north of the Scottish mainland, feeling as though I had travelled to a rather remote part of the world. I couldn’t have been more wrong. Orkney may feel isolated today, but when the Atlantic was bridged with boats instead of planes flying out of densely populated southern urban centres, Orkney was much more central.

Maps of the world on display in Orkney did not have the equator as the centre of the image. Rather, they tilted the globe northward, bringing into focus areas of the northern Atlantic which usually shrink into obscurity- including Orkney itself. By changing the angle from which I considered the globe, I was able to see connections that had never before been made clear to me. One of those connections bridged the wide watery expanse between Orkney and western Canada.

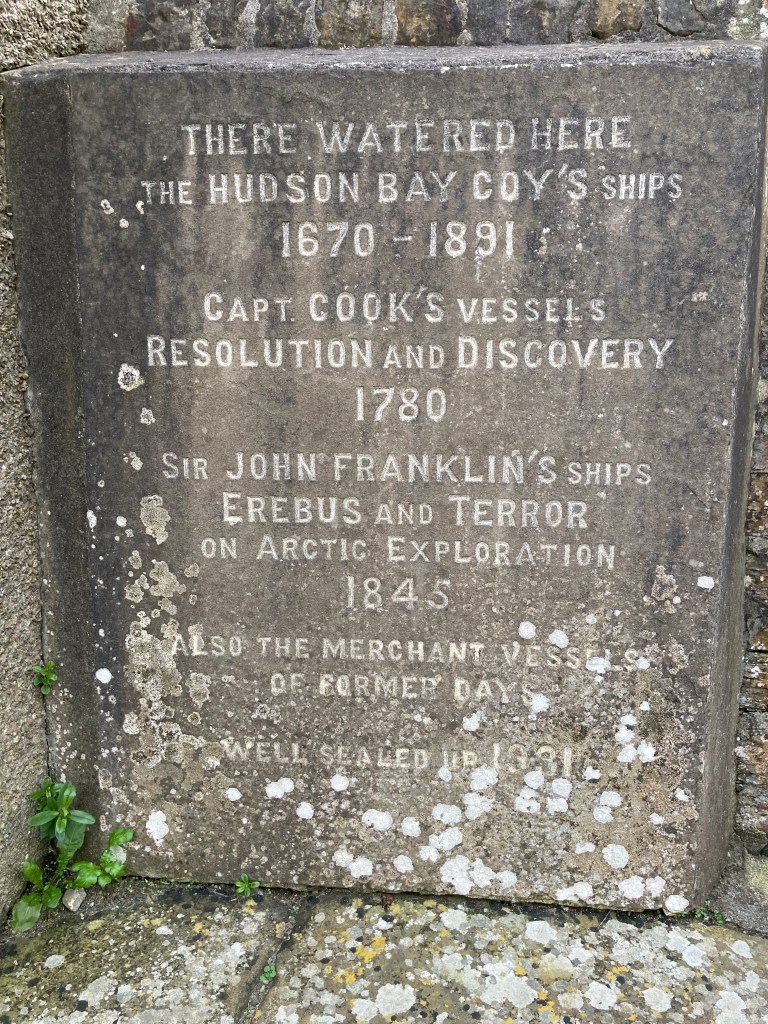

Orkney’s northerly latitude made it a geographically convenient place for the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). The oceanic entrance to the Hudson Bay is substantially further north than the mouth of the St. Lawrence seaway, which means that starting the journey from Orkney makes far more sense than leaving from a “more central” port in southern England. Hudson Bay-bound ships “called in” (made a stop at) at the Stromness harbour on the western edge of Orkney as their last landing place before braving the Atlantic crossing. Once in this harbour, they visited Login’s Well (pronounced “Logan’s”) to fill their all-important supplies of drinking water.

But it wasn’t just Orkney’s fresh water the HBC wanted. Orkney’s men were also in high demand.

Read more