Editor’s note: The banner image above is courtesy of the Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary.

Cowritten by: Fraser Shaw, Heritage Conservation Advisor and Ronald Kelland, Geographical Names Program Coordinator

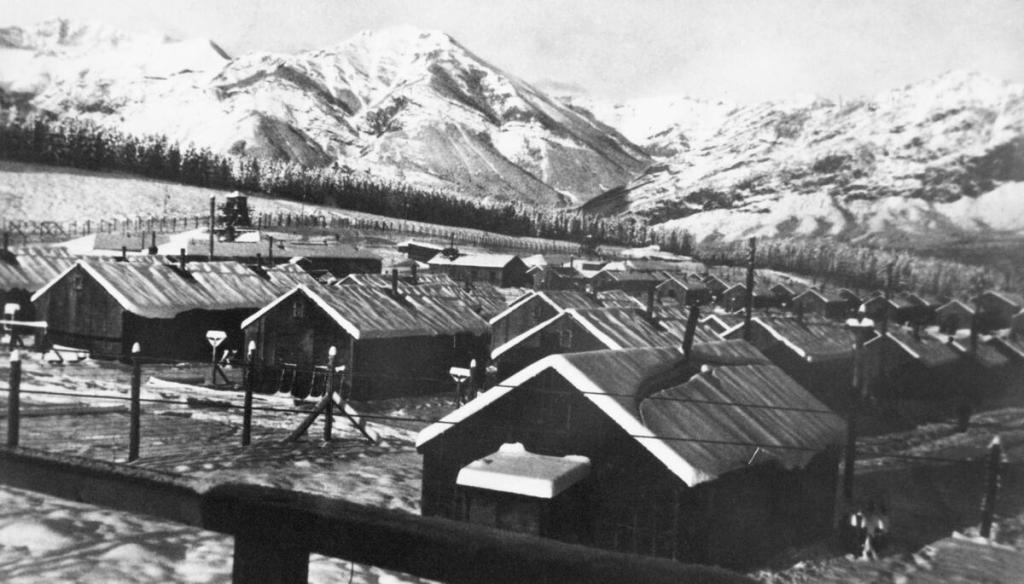

A panoramic 1945 photograph shows a snowbound mountain landscape in the grip of winter. Plumes of smoke rise from rows of tarpaper-covered buildings huddled behind barbed wire fences and guard towers. This is Camp 130, one of a series of Prisoner of War (POW) camps established across Canada during the Second World War. Outside the prisoners’ compound is a small, single-story log cabin occupied by the camp commandant. Built in 1936, the “Colonel’s Cabin” was protected as a Provincial Historic Resource in 1982 as one of few remaining structures in Alberta directly linked to the internment of prisoners of war and to recognize the site’s earlier association with the Kananaskis Forest Experimental Station.

During the Great Depression, Canada’s middle-class, political and economic elites were concerned about the large number of unemployed men roaming the country and how that long-term unemployment might result in moral degradation, petty criminality and the fostering of revolutionary communist ideology. Under pressure from religious organizations and municipal and provincial governments, the Dominion government established a series of temporary work camps for single, unemployed men to be administered by the Department of National Defence. By 1936, camps had been established at Acadia, New Brunswick; Valcartier, Quebec; Petawawa, Ontario; Duck Mountain, Manitoba; and Kananaskis, Alberta. Ostensibly created to engage unemployed and homeless men in work that was seen as being necessary for their physical, psychological and spiritual betterment, the camps also kept these unemployed, transient men out of sight and far from transportation routes and urban centres.

Read more