Written by: Ronald Kelland, Geographical Place Names Coordinator

Remembrance Day, November 11, is the day Canadians honour and memorialize those who gave their lives while in military service. While honouring all Canadian service personnel this Remembrance Day, this year RETROactive is drawing attention to a few geographical features named to commemorate casualties of the Second World War. Following the Second World War, the Province of Alberta, through collaboration between the Geographic Board of Alberta and the Geographic Board of Canada began naming geographical features, mostly lakes, for decorated military personnel from Alberta that were casualties of the Second World War. This is the story of two of those individuals.

Located approximately 35 kilometres northwest of Bonnyville is Conn Lake.

The lake is named for Leading Steward James Conn. Born at Hillcrest, Alberta on December 7, 1914, Conn was the son of John Robert (died 1921) and Lillian Maude Conn (died 1916). At some point, James and his siblings moved to Quebec and by 1932 James Conn was living on University Street (now Robert-Bourassa Boulevard) in Montreal.

At the outbreak of the war, James Conn was a waiter with the Canadian Pacific Railway. Conn enlisted in the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve in August 1943 and trained at Navy Reserve Divisions HMCS Montreal (now HMCS Donnacona) and at Winnipeg with HMCS Chippawa and at Ottawa with HMCS Carleton. He served a short stint on HMCS Stadacona, a steam yacht that had been acquired by the Royal Canadian Navy in 1915 and was used as a home waters patrol vessel during the Second World War. On October 17, 1944, he reported to HMCS Esquimalt at the rank of Leading Steward.

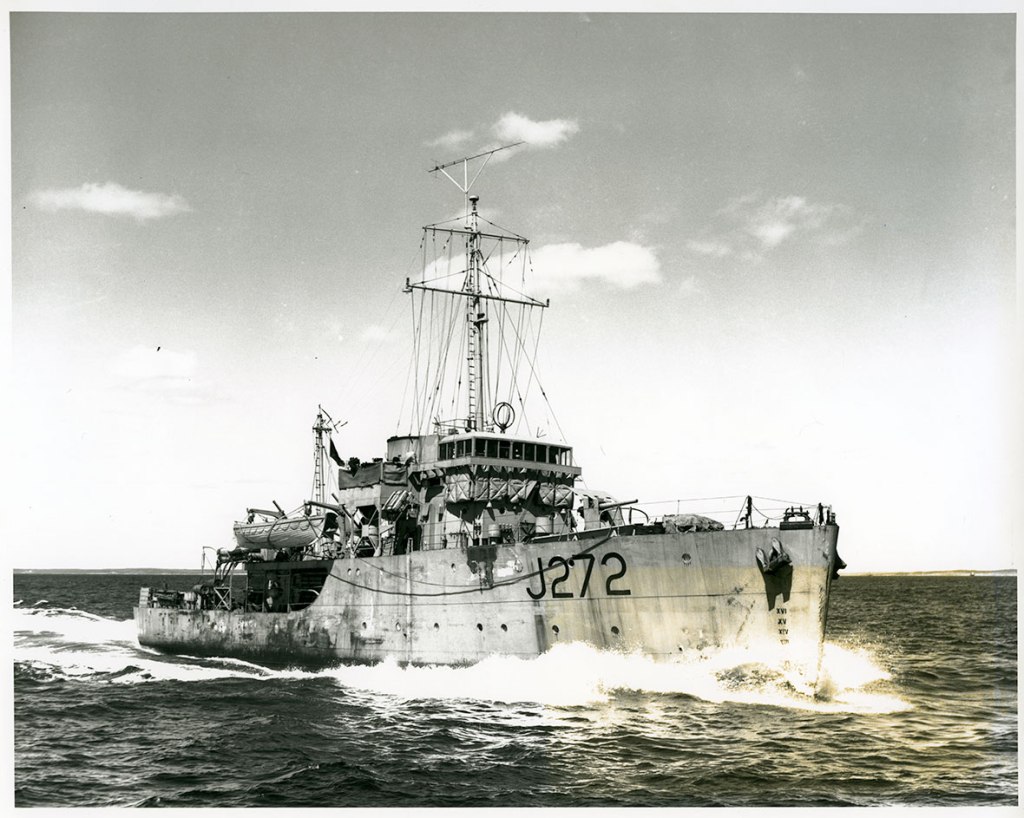

HMCS Esquimalt was a Bangor-class minesweeper operating out of the port of Halifax to hunt enemy submarines and keep approaches to the harbour clear of mines. Named for the Township of Esquimalt on Vancouver Island, she was launched in 1941 and was originally assigned to patrol duties off Newfoundland and was transferred to Halifax in September 1944. On 15 April 1945, Esquimalt sailed on a patrol to hunt a German U-boat that was suspected to be in the waters near Halifax. At approximately 6:30 a.m. on the morning of April 16, with the lights of Halifax visible on the horizon, a torpedo from German U-boat U-190 struck Esquimalt on its starboard, flooding the engine room and causing a loss of power. In less than five minutes, and before a distress call could be sent, Esquimalt rolled onto her starboard side and sank beneath the surface.

Sources differ regarding the number of sailors lost in the sinking of HMCS Esquimalt, with a range of 39 to 44 crew perishing that night either going down with the sinking vessel or of exposure in the frigid waters awaiting rescue. Six hours after the sinking, survivors were picked up by Esquimalt’s sister ship, HMCS Sarnia. Twenty-seven of Esquimalt’s crew survived. Leading Steward James Conn was not one of them

Read more