Editor’s note: The banner image above is courtesy of the Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary.

Cowritten by: Fraser Shaw, Heritage Conservation Advisor and Ronald Kelland, Geographical Names Program Coordinator

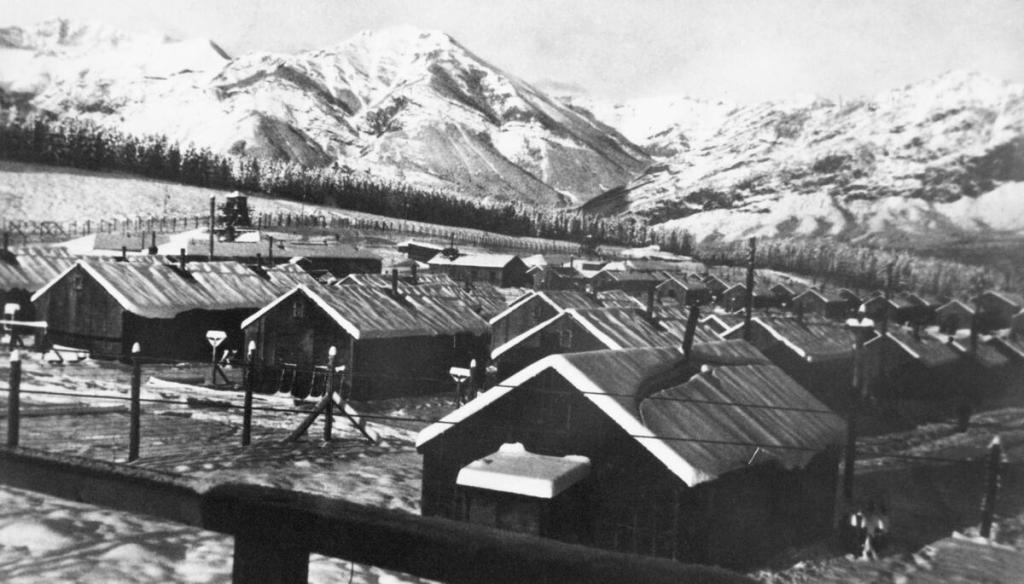

A panoramic 1945 photograph shows a snowbound mountain landscape in the grip of winter. Plumes of smoke rise from rows of tarpaper-covered buildings huddled behind barbed wire fences and guard towers. This is Camp 130, one of a series of Prisoner of War (POW) camps established across Canada during the Second World War. Outside the prisoners’ compound is a small, single-story log cabin occupied by the camp commandant. Built in 1936, the “Colonel’s Cabin” was protected as a Provincial Historic Resource in 1982 as one of few remaining structures in Alberta directly linked to the internment of prisoners of war and to recognize the site’s earlier association with the Kananaskis Forest Experimental Station.

During the Great Depression, Canada’s middle-class, political and economic elites were concerned about the large number of unemployed men roaming the country and how that long-term unemployment might result in moral degradation, petty criminality and the fostering of revolutionary communist ideology. Under pressure from religious organizations and municipal and provincial governments, the Dominion government established a series of temporary work camps for single, unemployed men to be administered by the Department of National Defence. By 1936, camps had been established at Acadia, New Brunswick; Valcartier, Quebec; Petawawa, Ontario; Duck Mountain, Manitoba; and Kananaskis, Alberta. Ostensibly created to engage unemployed and homeless men in work that was seen as being necessary for their physical, psychological and spiritual betterment, the camps also kept these unemployed, transient men out of sight and far from transportation routes and urban centres.

At the Kananaskis station, the men were used on forestry projects, harvesting trees for lumber, clearing areas burned by forest fires, road clearing and construction, telegraph line installation and the building of camp facilities. The latter included a superintendent’s cottage built in 1936 that is likely the structure known today as the Colonel’s Cabin. The men also assisted with legitimate forestry research projects under the direction of research forester H.A. Parker, such as planting and transplanting tree species, tending nursery beds and monitoring vegetation regrowth following a forest fire.

In the early days of the Second World War, the Kananaskis Forestry Experimental Station became a prisoner-of-war camp. In 1939, Lieutenant-Colonel Hugh de Norban Watson, a member of the Veterans Guards of Canada and veteran of the First World War, was appointed commandant of the camp, which was renamed Camp K and converted to a POW camp. Watson moved into the forestry station’s superintendent’s cabin, which became known as the Colonel’s Cabin.

The Kananaskis site was used to detain a variety of prisoners over the course of the war. Initially, enemy non-combatants, or Class II Prisoners of War as defined by the 1929 Geneva Convention, were detained at the camp. These Class II prisoners consisted of German and Italian nationals residing in Canada at the outbreak of hostilities and people with known or suspected ties to both fascist and communist parties. They were also joined by captured merchant seamen from Axis nations. Also detained were Canadians of German or Italian origin that had emigrated to Canada years prior to the war. Many of these detainees were farmers, doctors, merchants and blue-collar workers and were detained simply because of their German, Austrian or Italian origins or suspicions, largely unfounded, that they represented a threat to Canada.

In June 1940, the governments of Canada and the United Kingdom reached an agreement by which Canada would accept 7,000 captured Axis military personnel, or Class I Prisoners of War (a number that would eventually grow to about 35,000). The Class II prisoners-of-war were moved out of the Kananaskis camp and the Class I prisoners-of-war, largely officers, were moved into the camp, now called Camp 130. Another group of people detained at the Kananaskis camp during the war were conscientious objectors or people on alternative service. These were Canadian citizens that refused to serve in the military, largely due to religious convictions. Rather than serve in the armed forces when called to do so, these conscientious objectors could chose or be sentenced to detainment in an alternative service camp to work on agricultural, forestry and construction projects.

The prisoners of the camp carried out projects similar to those undertaken while the site was a research station and unemployed labour camp. Under the 1929 Geneva Convention, Class I prisoners-of-war could not be used for labour that directly benefited the Allied war effort, meaning they could not be forced to work in munitions or armaments factories. However, they could be used for agricultural and forestry work as well as on road clearing, construction and other infrastructure projects. The harvesting of timber remained a common project, with particular emphasis on the harvesting and cutting of logs for pit props, which were used as roof supports in mines. Some Camp 130 prisoners-of-war were transported to Brooks, Alberta where they performed agricultural labour during the fall harvest season, particularly in the sugar beet fields. A major project in which Camp 130 prisoners were instrumental was clearing of a portion of the Kananaskis River valley in preparation for the reservoir, now known as Barrier Lake, that would result from the construction of the Barrier Dam.

The prisoners of Camp 130 were afforded considerable latitude regarding confinement and leisure. Generally, the prisoners of war in Canada were treated well during their confinement. Canada strictly adhered to its responsibilities to the prisoners of war as required under the Geneva Convention and was also highly conscious that mistreatment of Axis prisoners could result in reprisals against Canadian and other Allied prisoners of war being held by Axis powers. This concern, perhaps coupled with the isolation of the Kananaskis camp, led Camp 130’s administration and guards to give the prisoners considerable leeway regarding confinement and leisure. Prisoners are known to have been allowed to leave the camp to fish and trap wildlife and some prisoners climbed the nearby Mount Baldy.

However, while not all German military personnel were members of the Nazi party or held pro-Nazi beliefs, many were. Canadian officials attempted to distinguish the prisoners with strong pro-Nazi beliefs, classified as so-called “Black” prisoners, from those with strong anti-Nazi beliefs, or “White” prisoners and those somewhere in between, or “Grey” prisoners. Attempts were made to segregate the Black prisoners from the Whites and Greys to minimize their influence in the camps, protect the anti-Nazi prisoners and make the Grey prisoners more amenable to Canada’s de-Nazification re-education programs. These segregation efforts had limited success largely due to the sheer number of prisoners of war. By the end of the war, only about 9,700 of 35,000 prisoners had been assessed. Camp 130 became a designated Black camp where strongly pro-Nazi prisoners would be sent, although the Kananaskis camp in reality represented a mix of all ideological categories.

At the end of the war, camp prisoners were repatriated to their homes and the site returned to its earlier use as a research station for the Canadian Forestry Service. Anecdotally, it has been said that memories of their good treatment in Canada, and at the Kananaskis camp in particular, led many former German prisoners of war to emigrate to Canada in the years following the war. No study has been done of this phenomenon and it is just as likely that many left Germany due to the privations of post-war life in that country and Canada may have just been the most convenient and familiar destination.

In the decades following the closure of Camp 130, most of the site was cleared and the buildings, assembly yards, fencing and guard towers were removed. But the Colonel’s Cabin and a modified former guard tower, foundations and other elements survived. In 1973, the federal government planned to demolish the cabin but Alberta Forestry Service staff convinced the provincial department of Culture, Youth and Recreation to intervene and demolition was postponed. The site was acquired by the Government of Alberta in 1980 and the Colonel’s Cabin was designated as a Provincial Historic Resource in 1982. Today, the redeveloped research station and prison camp serves as the Barrier Lake Field Station for the University of Calgary’s Biogeoscience Institute.

Designation and conservation

Alberta Forestry and Parks owns and maintains the historic structure, while University of Calgary staff have promoted and interpreted the site’s unique history to visitors. By 2017, after a remarkable 40-plus years of service, the weathered cedar shingle roof urgently needed replacement to prevent water damage and decay of the log structure and wood interior. After an assessment of the building, planning in consultation with Alberta Parks and the Kananaskis Improvement District, and with coordination by the Historic Resources Management Branch, private contractors installed a new cedar shingle roof in February 2024 under challenging winter conditions probably much like those in the 1945 photograph.

The new cedar shingle roof is a Class A fire-rated installation that maintains the cabin’s historic appearance while mitigating vulnerability to wildfires and meeting municipal development regulations. Where the four-decade old roof exemplified the resilience of traditional materials, the new roof illustrates the adaptation of such materials to meet new performance requirements. Future conservation at the site will be guided by a FireSmart assessment that takes into account risks posed by surrounding vegetation and the inherent combustibility of a log structure. Upcoming work phases will likely include repairs to the log structure, repair of the massive Rundlestone chimney, window repairs and other remedial work.

The inset photograph looks south through the camp gates past a small log building unlike the tarpaper-and-batten exteriors of camp structures. This distant and partial view may be the only historic photograph of the cabin. Enlarged at upper right, the porch is absent and appears to be a post-war addition. The stove chimney at the apex of the pyramidal roof is missing today and trees may hide the large Rundlestone chimney. Source: Historic Resources Management Branch; photo courtesy of W.K Jull.

Roof replacement in February 2024 fortunately revealed minimal rot limited to the front eave, exposed log rafter tails, and the chimney perimeter (inset upper right). This attests to the quality of the previous installation and the inherent durability of No. 1 grade cedar shingles on traditional roofing felt. Source: Chalmers Heritage Conservation and Martineau Roofing.

In the image below, you can see the Colonel’s Cabin in March 2024 with its new roof. The traditional-looking roof is in fact a Class A fire-rated assembly with No. 1 grade cedar shingles impregnated with fire retardant installed with stainless steel fasteners over fire-resistant fibreglass-reinforced underlayment on the original solid shiplap deck. The installation satisfies both municipal development requirements and Cedar Shake and Shingle Bureau recommendations for fire-resistant roofs.

New prefinished aluminum eavestroughs blend into the historic wood exterior as a compatible new element to provide effective roof drainage. The wood gutters they replace, while interesting, were in fact not historic based on photographic records of the cabin since the 1970s.

At lower right, new rafter ends replace rotted material with carefully splicing into the intact existing lodgepole pine rafters. The porch is believed to be a post-war element but has been retained to protect the structure while research into the cabin’s evolution continues.

Sources

Candy, R.H. “The Petawawa Unemployment Relief Project,” The Forestry Chronicle, vol. 10 no. 1, 14-18, available from https://pubs.cif-ifc.org/doi/pdf/10.5558/tfc10014-1.

Carter, David J., Behind Canadian Barbed Wire. (Calgary: Tumbleweed Press, 1980).

Goethe Institut, “German Traces in Alberta: The Seebe Camp 130: WWII Internment Camp,” [webpage], available from https://www.goethe.de/ins/ca/en/kul/ges/dsk/dsa/21808410.html.

Kelly, John Joseph. “Intelligence and Counter-Intelligence in German Prisoner of War Camps in Canada During World War II,” Dalhousie Review, vol. 58 no. 2, 285-294, available from https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/bitstream/handle/10222/60063/dalrev_vol58_iss2_pp285_294.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y#:~:text=In%20view%20of%20the%20constant,See%20be%20was%20a%20mixture.

Krawchuk, Peter, Interned Without Cause: The Internment of Canadian Antifascists During World War Two, (Toronto: Kobzar Publishing Co., 1985), available from https://www.marxists.org/history//canada/socialisthistory/Docs/CPC/WW2/IWC00.htm.

Northern Forest Research Centre, Forestry Service, Environment Canada. The Kananaskis Forest Experiment Station, Alberta (History, Physical Features, and Forest Inventory). C.L. Kirby. Information Report NOR-X-51, Ottawa: Government of Canada, January 1973.

O’Hagan, Michael, “Beyond the Barbed Wire: POW Labour Projects in Canada during the Second World War” PhD diss., Western University, 2020. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6849. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6849.

“Camp 130 – Kananaskis/Seebe (Camp K),” POWs in Canada [blog post], available from https://powsincanada.ca/pows-in-canada/internment-camps/camp-130-kananaskis/

Stanton, John. My Past is Now: Further Memoirs of a Labour Lawyer. (St. John’s: Canadian Committee on Labour History, Department of History, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1994), available from https://www.aupress.ca/app/uploads/cclh07_99Z_Stanton_1994-My_Past_Is_Now.pdf.

Swift, D. Edwin, et al. “Acadia Research Forest: A Brief Introduction to a Living Laboratory,” Long-term Silvicultural & Ecological Studies” Results for Science and Management. (New Haven: Yale University, School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, 2006), 104-118.

Venes, J.C., “The Acadian Forest Research Station,” The Forest Chronicle, vol. 13 no. 3, 465-469.

Zimmerman, Ernest Robert, The Little Third Reich on Lake Superior: A History of Internment Camp R. (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2015).

just a quick note to tell you my husband and I really appreciate these informative emails. Please keep them coming. You have fans!