RETROactive has been publishing for almost three years now. We will continue to be your source for news and information about Alberta’s historic places.

At the same time, we’re going to start bringing you articles providing insight into other aspects of Alberta Culture’s work to understand, protect and conserve historic resources. This post is the first showcasing the work of Alberta’s Archaeological Survey.

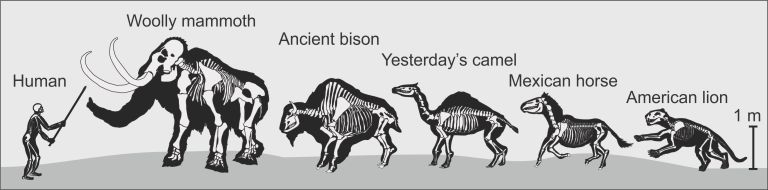

By the time Europeans and their guns arrived, 250 years ago, in the place that would become Alberta, the area had already witnessed 10,000 years of big game hunting. Alberta’s prehistoric hunters killed mammoth, an extinct horse, an over-sized species of extinct bison, and even camels that roamed the plains millennia ago (Figure 1). Analyses of stone tools have revealed traces of mammoth and horse blood on spear tips in northeast Alberta and southwest of Lethbridge, respectively. Other evidence of prehistoric big game hunting includes human-made cut marks on animal bones found with stone tools.

At eight tons and over three meters tall, the woolly mammoth towered over human hunters. So how did people with thrusting spears bag this massive grazer without being gored? Most likely with ingenuity and teamwork. Mammoths, as well as horses and large bison are herd animals that were probably corralled into situations that gave people the upper hand like bogs, canyons, and cliffs where lumbering prey would get trapped or stuck in the mud. In addition to the dangers of hunting big animals, people also had to contend with big predators like the now-extinct American lion, which has been found in Calgary and Edmonton. It was taller than a polar bear (but much faster) and likely kept people on fearful watch.

By 8,000 years ago, Alberta hunters acquired a new weapon that put some distance between themselves and future food: the atlatl (spear thrower) and dart (a short spear). The atlatl enabled people to throw weapons with much greater force (Figure 2).

Around 2,500 years ago, stone tips on ancient weapons become much smaller which indicates the arrival of bow and arrow technology. The bow and arrow was effective at about 30 m away (Figure 3) so why adopt a new hunting system that required people to get closer to big game than the older atlatl?

Imagine wearing a blind-fold on an autumn day and listening to the difference between a stationary archer and a javelin thrower lunging across the dry leaf litter. The bow and arrow was quieter because it required much less movement and it was also more accurate.

Several other hunting technologies existed in addition to spears, darts, and arrows. Bison and pronghorn antelope were stampeded over cliffs and canyons (Figure 4);

Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump near Fort Macleod is a world famous example that was used for over 5,000 years. Small piles of stone were built in converging lines creating drive lanes that extended several kilometres. These piles stabilized branches and leather strips that waved in the wind and frightened bison, which were funnelled down the drive lanes and over steep cliffs. Up to 200 animals could be killed in one day. Buffalo jumps are one of the largest prehistoric meat-capturing events on the planet and it happened thousands of times over thousands of years on the rolling prairies of Alberta.

Moose, elk, deer, and caribou were snared, stalked in deep snow, and speared from boats while swimming. In the winter, beaver and bears were speared in dens and lodges. Alberta’s early hunters called game with birchbark horns, rubbed scapulas on trees to imitate antler raking, dressed in coyote skins to more easily approach bison, and regularly burned small areas to stimulate plant growth that attracted big game. Archaeology tells a story of thousands of years of successful big game hunting strategies. While archaeologists have learned a great deal about ancient hunting, much remains to be discovered.

Alberta Culture’s Archaeological Survey maintains records of new archaeological discoveries across the province to enable their protection. If you come across an arrow head or other stone tools, please take a few photographs or jot down some notes to share with us so we can continue to learn about the province’s rich hunting history. You can contact the Archaeological Survey at 780-431-2300.

Written by: Todd Kristensen, Northern Archaeologist & Darryl Bereziuk, Director, Archaeological Survey.

Thanks Matthew; we need more articles of this kind in order to understand our own deep past. Provincial Archaeologist, Daryll Bereziuk, took several steps in that direction at our Year 2 of 4: “Blessing of the River Ceremony” last April at Battle River. We will print off this copy of your article for use at the Year 3 of 4 ceremony this May 10.

Reblogged this on Canmore History.