In August of 1914, Canada entered the First World War, an arduous experience for Albertans who served on the battlefront and for those who remained in Canada. Thousands of men enlisted and quickly left Alberta for the front, leaving a gap in both the workforce and civil society. During the war, women took on many of these roles, opening a realm of new possibilities. Women helped raise funds for the Canadian Red Cross Society and entered the workforce, while others enlisted in the medical core as nurses. This post will give an overview of Canadian women in the First World War by looking at the shift in traditional labour roles, Canadian nurses and the voluntary initiatives that women organized. It is important to recognize the sacrifices that were made by these women and to show how they contributed to the war effort, on the home front as well as overseas.

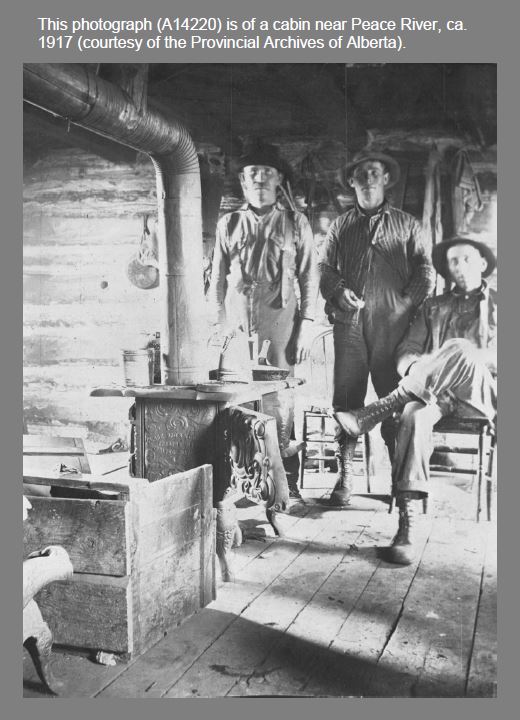

For most Canadian women, participation in the First World War was limited to serving on the home front. With almost 50,000 of Alberta’s men deployed overseas, this created openings in the service and farming industries back home. The demand for more workers increased and jobs that were traditionally reserved for men were opened to women for the first time. The need for additional labour differed by region across the country. Central Canada, for instance, experienced a greater need for employees to work in munitions factories, while in Alberta, labourers were needed to assist with farm work. Other positions that women filled were administrative clerks, factory workers and as delivery vehicle drivers. Female participation in the clerical and banking fields increased significantly and there were women who remained in this line of work even after the war ended. Women were exposed to more job opportunities than ever before, whereas prior to the First World War, they were largely limited to domestic duties.

Between 1914 and 1918, there was an overwhelming need for labour and this compelled employers to hire women. Many employers, and even some women, viewed the female worker as a temporary substitute needed to meet a wartime emergency. Not surprisingly, women faced opposition at times for their participation in the workforce, particularly during the initial outbreak of the war in the street railway service and banking fields. In several cities across Canada, male workers with the railway system were outraged that women were allowed to be hired as conductors on their cars. While some areas disapproved of women taking on non-traditional labour roles, other employers recognized that women were a much needed source of labour. The Canadian government hired 1,325 women in civilian jobs, such as clerks and typists, with the military. Another 1,200 women were employed by the Royal Air Force in Canada to work in mainly technical positions, and by 1918, they had hired 750 female mechanics. This indicates that the prejudice against working women had to be overruled in order to alleviate the shortage of manpower. The war produced a necessity for human labour and this opened up a wider array of opportunities for women. The roles that women stepped into during the war years had a significant impact on the province by challenging traditional gender roles and began legitimizing the idea of women in the labour force.

Many women initially entered the labour market to demonstrate their patriotism, but this move had a number of positive effects. There was an increase in financial opportunities for women and wage disparity between men and women began to lessen. In addition, the war opened up a whole host of social opportunities. Women were participating more in the public sphere, both in the workforce and social circles, and this provided the foundation for a fervent energy that helped to ignite the women’s movement across Canada. Women desired greater participation in politics and the idea that women should vote and run for office quickly became mainstream. On April 19, 1916, this right was granted to Alberta women. Obtaining the vote was an achievement which contributed to an increased political consciousness amongst women in Alberta. This momentum continued and by the following year, Louise McKinney and Roberta MacAdams, had become the first women to be elected to the Alberta legislature. The dramatic increase of women in the labour field and social community was a significant force that paved the way for women’s rights in Canada.

There were a number of Canadian women who contributed their services abroad, primarily in the medical service field. The Canadian Army Medical Corps required a number of trained nurses to help provide medical care to Canadian soldiers. Trained nurses joined the Nursing Sisters of Canada and there was no shortage of volunteers. 3,141 nurses served in the medical core, with 2,504 of those serving overseas. There were women from Alberta who enlisted as military nurses and at the initial outbreak of the war in 1914, 10 nurses from Edmonton went abroad and assisted the troops serving on the front. Canadian nurses worked tirelessly to provide medical services to those who were wounded in battle and cared for recovering soldiers. They were commonly known as “bluebirds” due to their uniform colours. Later on, the nurses were referred to as the “Sisters” or “Angels of Mercy” by the soldiers. These monikers are indicative of the caring service that the nurses provided and were often praised for. Throughout the First World War, Canadian nurses were commended for their heroism and became well known for their compassion when treating the afflicted.

Women without nursing experience could enlist through the Voluntary Aid Detachment which was operated by the Canadian branch of the St. John Ambulance. V.A.D. nurses received basic first aid training and worked in hospitals as medical assistants and carried out general duties such as cooking and cleaning. The role of the V.A.D. allowed women who were not trained as nurses to be directly involved in the war efforts and approximately 2,000 Canadian women served as unpaid nurses during the First World War. Around 500 were sent to Europe and the majority remained at convalescent hospitals in Canada. Nine Edmonton women were trained as V.A.D.s and deployed overseas.

The First World War brought changes to the military medical services. Medical units were originally established in hospitals and then Casualty Clearing Stations were created near the frontlines to give faster treatment to the soldiers injured in battle. While this provided better service for the wounded, it put Canada’s nurses closer to combat. They faced the danger of enemy artillery attacks, air raids and also endured vermin, fleas and disease, just as the men in the trenches. Canadian nurse, Katherine Wilson-Simmie, details her account in The Memoirs of Nursing Sister Kate Wilson, Canadian Army Medical Corps, 1915-1917. While stationed near the front lines, Wilson-Simmie witnessed an unforgettable day when the first gassed soldiers were admitted for medical assistance. She describes the event as “an entirely new kind of warfare – horrible, and contemptible. It was a terrible experience for the men and for those trying to help them.” Women not only observed the abysmal conditions of war, they were eyewitness to the immediate impact that battle had on human life.

As the nurses returned from overseas, they could take pride in the contribution that they had made for their country, but they had also witnessed firsthand the devastating toll of war. Approximately 50 Canadian nurses lost their lives in the First World War. The Canadian Nursing Sisters are commemorated at The Nurses’ Memorial on Parliament Hill, Ottawa.

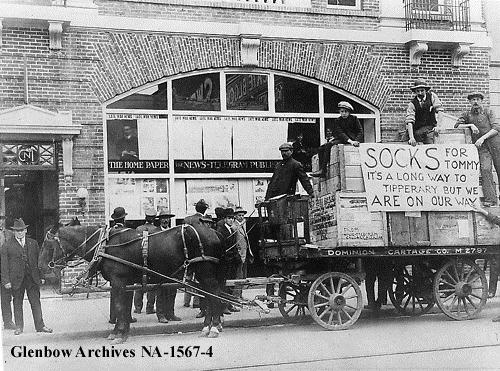

Women supported numerous initiatives across Canada and overseas during the First World War, but the Canadian Red Cross Society (CRCS) was the primary humanitarian organization in the country. Women were eager to serve the Red Cross which gave them the opportunity to participate in the war from the home front. The society provided aid and comfort to soldiers and their families who were affected by the war and women supported these relief efforts in a number of ways. They fundraised, distributed gifts, prepared care packages and medical supply kits as well as knitted extra clothing to send to soldiers.

When the war was declared, women endorsed the work of the Red Cross Society without hesitation and a number of auxiliaries emerged across the country during this time. This support allowed the Canadian Red Cross to provide relief assistance and volunteers visited recovering soldiers in British hospitals, attempted to trace missing people and helped Canadians correspond with their families and friends abroad. The society also worked with Red Cross affiliates overseas to fulfill requests for medical assistance when possible. A volunteer, and later Alberta resident, Madeleine Jaffray, was one of ten Canadian nurses who were recruited through the Red Cross to serve in the French Flag Nursing Corp. In Belgium, just miles from the frontlines, Jaffrey’s unit was frequently targeted by bombs. During one attack, her foot became severely wounded and was later amputated. She was awarded a French military medal, the Croix de Guerre, for her service and was the first Canadian woman to receive this honour.

With the help of donors and dedicated volunteers, the Canadian Red Cross Society established a headquarters in London, so they could better coordinate with the people on the front line in France. The organization also helped to create and maintain hospitals for soldiers who were wounded in battle. The Red Cross played a significant role by providing comfort and support services to Canadians. This was made possible through the voluntary services that were initiated by women on the home front. The Red Cross was a valuable organization in a time of need and gave women a variety of ways to help their loved ones who had gone overseas to war.

Alberta women contributed to the Canadian efforts to win the First World War in many ways. Initial participation in the war efforts was largely out of patriotic respect, but a number of outcomes emerged as a result. Notably, there was an increased female presence in civil society and the Alberta suffragist movement emerged. The efforts displayed by women during the Great War are remembered for the impact that they have had on women’s history in Canada.

This was the second part of a series commemorating the First World War. This series will look at a range of topics that will show Alberta’s involvement in this historic event.

To learn more about women in Alberta’s history, refer to the Alberta Women’s Memory Project, an initiative that was created to preserve and promote the history of women in Alberta.

Written by: Erin Hoar, Historic Resources Management Branch Officer

Sources

Byfield, Ted, ed. Alberta in the 20th Century: The Great War and its Consequences 1914-1920. Vol. 4. Edmonton, Canada: CanMedia Inc., 1995.

Canadian Red Cross. “The First World War: 1914-1918.” (Accessed August 5, 2014).

Canadian Great War Project. (Accessed August 19, 2014).

Canadian War Museum. (Accessed August 5, 2014).

Dundas, Barbara. A History of Women in the Canadian Military. Montreal: Art Global and Department of National Defense, 2000.

Glassford, Sarah, and Amy Shaw, eds. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland During the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2012.

Love, David W. A Nation in Making: The Organization and Administration of the Canadian Military During the First World War. Vol. 2. Ottawa: Service Publications, 2012.

Nicholson, G.W.L. Canada’s Nursing Sisters. Toronto: Samuel Stevens Hakkert & Company, 1975.

Payne, Michael, Donald Wetherell, and Catherine Cavanaugh, eds. Alberta Formed Alberta Transformed. Vol. 2. Edmonton, Canada: University of Alberta Press, 2006.

Veterans Affairs Canada. “The Nursing Sisters of Canada.” (Accessed August 6, 2014).