On a cold January day researchers from the University of Alberta and the province’s Archaeological Survey huddled on a frozen lake near Fort McMurray waiting to extract long cores of mud. Layered throughout the cores are environmental indicators, like pollen and microorganisms, that span thousands of years. Geologists have tried to map the boundaries of hydrocarbon reservoirs in the oil sands for over a century but they have only recently focused on the natural forces that exposed bitumen to human eyes. The mystery of this exposure event is what continues to draw researchers to remote frozen lakes in northeast Alberta. Read more

Category: Alberta’s history

Alberta’s Wooden Country Grain Elevators

This post was originally published on RETROactive on March 6th, 2012. Farmers across the province will soon be busy with harvest so we thought it appropriate to highlight a previous post associated with Alberta’s agricultural past. Please note that these statistics are from 2012.

The twentieth century saw the rise and fall – literally – of the wooden country grain elevator in Alberta. As rail lines spread across the province, grain elevators sprouted like mushrooms after a spring rain. The high water mark for wooden country grain elevators was in 1934. New elevators were added in every decade, but this has been exceeded by the rate of demolition or closure ever since. Check out the following “index” of Alberta’s wooden country elevators, called “elevators” for short in this list.

Number of elevators in Alberta:

- in 1934: 1,781

- in 1951: 1,651

- in 1982: 979

- in 1997: 327

- in 2005: 156

- in 2012 on railway rights-of-way: 130

Number of communities with:

- at least one elevator: 95

- 2 or more elevators: 26

- 3 or more elevators: 7

- 4 or more elevators: 1 (Warner)

Additional statistics:

- Number of elevators in Alberta’s longest row: 6

- Oldest remaining elevator: 1905 (Raley)

- Number of remaining elevators that pre-date 1910: 3 (Raley, St. Albert, De Winton)

- Newest remaining elevator: 1988 (Woodgrove)

- Decade with the largest number of surviving elevators: 1920s (33)

- Decade with the second largest number of surviving elevators: 1980s (26)

- Decade with the fewest (after pre-1910) number of surviving elevators: 1940s (5)

- Number of elevators that have been designated a Provincial Historic Resource (PHR): 13

- Number of communities with at least one elevator designated as a PHR: 10

- Oldest designated elevator: 1906 (St. Albert)

- Newest designated elevator: Leduc (1978)

For a list of communities in Alberta with designated and non-designated elevators, please click here.

Please Note:

- Grain elevators that have been moved off railway rights-of-way – to a farmyard or a museum, for instance – are not included in these statistics.

- Grain elevators located on railway rights-of-way where the rails have been torn up are included in these statistics.

- Concrete or steel elevators are not included.

- Elevators used for other purposes, such as seed cleaning or fertilizer storage, are not included.

- Most of these elevators were last documented by the Heritage Survey in 2005. It is possible that some of the elevators on the list are now gone.

Additional Information:

- View records for designated grain elevators on the Alberta Register of Historic Places.

- Explore the online Heritage Survey database, which has records for over 700 grain elevators.

- Read “Alberta’s Grain Elevators: A brief history of a prairie icon”, a Government of Alberta booklet, on the Alberta Grain Elevator Society website.

Written by: Dorothy Field, Heritage Survey Program Coordinator

Birch Bark Buccaneers and Prairie Paddlers: An Illustrated Look at Alberta’s Early Boating (Part 1)

It takes patience to fold steaming hot birch bark into a canoe and it takes power to hammer the planks of a lumbering sternwheeler. The products of Alberta’s early boat building were vessels that delivered families safe and sound to hunting grounds, glided fishermen over teaming shoals, and carried trade goods in an economic system that forged our province. This is the first of two blogs about some of the unique evidence of early boating in Alberta. The first blog explores First Nations boats and the second discusses early Euro-Canadian vessels from the adoption of the birch back canoe to steamboats.

Dug-outs and Bull Boats

First Nations’ boats on the plains were often made of buffalo hides stretched over willow or pine frames. This ‘bull boat’ was a small, circular craft quickly built from tipi hides and recycled shortly after. It enabled safe river crossings Read more

Floods, Bricks, and POWs: Rebuilding Medalta’s Historic Chimney

A massive brick chimney at Medalta Potteries towers six metres above the roof of “Building 10” and extends roughly the same distance from the roof to the dusty factory floor below. Two meters wide at its base, the chimney and accompanying boiler were vital in the production of clay products from the early decades of the twentieth century until the plant’s closure in the 1960s. Now a Provincial Historic Resource, Medalta Potteries in Medicine Hat has evolved into a vibrant community hub that includes the Medalta archives and interpretive centre, galleries and displays, a working pottery that reproduces classic Medalta ware, a contemporary ceramics centre for professional artists, and a venue for markets, weddings, concerts and other community events. The tall brick chimney and distinctive monitor roofs of the former factory buildings provide the iconic backdrop for these varied activities.

Already leaning slightly to the south, the chimney developed a worrisome new tilt after the June 2013 southern Alberta floods, an event which inundated much of Medalta and the nearby residential neighborhoods. As soil conditions on site gradually normalized in early 2014, the chimney’s foundation shifted and subsided further into the clay-rich soil, raising concerns about its stability. The only practical long-term conservation option was to disassemble the chimney and rebuild it with the original, locally manufactured brick using traditional masonry materials and construction methods.

Conserving the chimney started with extensive photographs and measurements followed by disassembly by a contractor specializing in historic masonry conservation. Medalta’s staff archaeologist monitored and documented the process. As the chimney came down brick by brick, unexpected finds within the masonry included an old whisky bottle; fire bricks from Hebron, North Dakota; and a bizarre series of wasps’ nests occurring at roughly one metre intervals within the stack. This corresponds roughly with the work a team of masons would likely have completed in a typical day – a coincidence that begs further explanation. The chimney-dwelling wasps turned out to be quite blind and fortunately did not harass the masonry crew as dismantling proceeded.

The most intriguing relic, however, was a cluster of bricks inscribed with names and the inscription “IX 44”, presumed to represent a date. The names went unobserved until mortar dust from the disassembly process settled lightly onto the brick and highlighted the writing. Prisoners of war interned in Medicine Hat during the Second World War were recruited for work in local industries to offset the wartime labour shortage. Research now underway may reveal that some of these POWs, possibly even masons in their pre-war lives, helped repair the chimney at Building 10 in September of 1944.

Chimney rebuilding is nearing completion and will replicate its historic appearance — without the lean to the south. Glazed bricks set into the chimney mark the locations of the autographed bricks and, soon, visitors to Medalta will be treated to a new exhibit in Building 10 featuring the original bricks and an account of this chapter in the site’s remarkable history.

Written by: Fraser Shaw, Heritage Conservation Adviser

Alberta & the Great War

To recognize the centennial of the First World War, the Provincial Archives of Alberta launched the Alberta & the Great War exhibit in August of last year. Using letters, photographs and formal war documents, this exhibit captures the experiences that Albertans endured during the Great War. There are five topics within the exhibit: the Western Front, Women and the War, Opposition and Oppression, the Home Front and the Aftermath, to show that there were several struggles going on at once during and after wartime. The effects of these events produced repercussions that remain evident in Alberta to this day.

The exhibit was assembled largely from the material found at the Archives, with a few artifacts on loan from the Royal Alberta Museum. Braden Cannon, a Private Records Archivist with the Provincial Archives of Alberta, will give an introduction to the exhibit that he curated.

The Great War had a tremendous effect on individuals and the province of Alberta as a whole. This display gives the public the opportunity to see into the lives of the Albertans who were at the forefront of the war and shows the impact of the conflict that reached the people back home. The archival materials used in the exhibit are a valuable record of this period in history. Exhibits, such as these, ensure that the individuals who served in the First World War and the substantial events of the past are not forgotten. Alberta & the Great War will run until August 29, 2015.

Video and summary by: Erin Hoar, Historic Resources Management Branch Officer. A special thank you to Braden Cannon at the Provincial Archives for appearing on video!

Pranks and Fun: Social Life at Old St. Stephen’s College

The history of Old St. Stephen’s College spans over a century and while the building itself is unique, it is the people have who have lived and worked here that bring out its uniqueness.[1] In its time as an educational facility, the college produced a large number of graduates who went on to become ministers, employed renowned educators and housed thousands of students. Residents participated in the traditions and customs of campus life and the building became eminent for the pranks that were carried out there. This post will look at the people of Old St. Stephen’s when it functioned as a theological college and some of the stories that illustrate the student’s social lives.

(Courtesy of the University of Alberta Archives, UAA 72-58-0294).

Students were the majority of the building’s inhabitants: up to 150 youths were housed in the college at once and they didn’t spend all their free time studying. After the First World War, the college installed steel spiraled slides, to be used as fire escapes, at the end of each wing. During this time, the college had become a convalescent home for injured soldiers and the fires escapes were meant to evacuate patients as quickly as possible in an emergency. The fire escapes were never used for their intended purpose, but the students made use of them for their own enjoyment. Freshmen were initiated by their fellow classmates, who would dump the unlucky first years down the slides and then chase them with buckets of ice water. This custom continued into the 1970s, up until the fire escapes were removed during the renovations and replaced with ladders. In addition to the pranks and hazing that took place, there were water fights with neighboring residences that highlight the enjoyment of student life on campus. The students had a great deal of playful fun here.

Another tale is from when the Rutherford Library was being constructed in 1948. On the evening of the cornerstone-laying ceremony, the cornerstone mysteriously disappeared, only to turn up behind the college’s west wing fire escape. The stone weighed 700 pounds, and everyone presumed that engineering students were the culprits. However, in 2008, the secret was revealed in New Trail, the University of Alberta’s Alumni magazine. The escapade was actually the work of a group of agriculture students living at St. Stephen’s College. Turns out, the students borrowed a milk cart from the St. Stephen’s kitchen and attempted to haul the stone as far as 109 Street. Being heavier than anticipated, they only made it as far as St. Stephen’s College. To the student’s dismay, the stone was discovered just hours before the cornerstone-laying and the ceremony proceeded as planned.

The tubed fire escapes on the wings of the building were installed in 1920.

Faculty members would also fall victim to the student’s pranks. The day after Halloween one year, John Henry Riddell, the College’s first principal, saw that his buggy was balanced unsteadily on one the building’s towers. Once again, the engineering students from the University of Alberta were thought to have assisted with this feat. Although no details could be found on who was responsible, it likely would have been worthwhile for the students to see the look on their administrator’s face. Pranks such as these were seemingly all in good fun, and as one former student states, they “built character and helped form fast friendships.”

In addition to pranks, there were Glee clubs, Students’ Council and various intramural activities for students to participate in. Physical recreation played a large role in student life at the college. Friendly sports rivalries were encouraged and the students had access to the tennis courts, a gym for basketball games and even skating parties were organized. Once the college’s ban on dances was lifted in the 1940s, students were able to attend university dances, including the well-known Sadie Hawkins Dance. Dormitory life helped to foster a communal atmosphere spirit among students and many residents have fond memories of their time spent at the college. Even the brochure for the St. Stephen’s Ladies’ College noted that “the social life [was] just delightful.”

When the building was home for the students of St. Stephen’s College, it was a place where friendships were formed, bonds between students and instructors were strengthened and fun was had. The building has seen thousands of staff and students pass through its hallways and numerous tales have been accumulated. These stories help to illustrate the liveliness of the former college and show us that it is the people who make history come alive.

What can you tell us about your time spent at Old St. Stephen’s College? Let us know your stories!

Written by: Erin Hoar, Historic Resources Management Branch Officer.

Sources:

Alberta Register of Historic Places. “Old St. Stephen’s College.” (Accessed September 10, 2014).

Designation File # 132, in the custody of the Historic Resources Management Branch.

Elson, D. J. C. “History Trails: Faith, Labour, and Dreams.” University of Alberta Alumni Association. (Accessed September 23, 2014).access

Schoeck, Ellen. I Was There: A Century of Alumni Stories about the University of Alberta, 1906-2006. Edmonton, Canada: The University of Alberta Press, 2006.

Simonson, Gayle. Ever-Widening Circles: A History of St. Stephen’s College. Edmonton, Canada: St. Stephen’s College, 2008.

“The Caper.” New Trail: The University of Alberta Alumni Association, 2008, 26-28 (Accessed September 13, 2015).

University of Alberta. “University of Alberta: St. Stephen’s College.” (Accessed September 10, 2014).

[1] A note on naming: the institution was initially known as Alberta College South. ACS and Robertson College were amalgamated in 1925 and renamed the United Theological College. The name St. Stephen’s College was chosen in 1927. It became known as Old St. Stephen’s College in 1952 when a new St. Stephen’s was built directly south of the existing college.

“Erin go Bragh” in Alberta

“What is the matter with the Calgary Irishmen?” asked a frustrated correspondent to the Calgary Herald in March 1916. The writer, who identified themself as ‘F. Fitzsimmons,’ was complaining about the city’s apparent lack of enthusiasm for St. Patrick’s Day, with no public events planned to celebrate the day. Fitzsimmons conceded that people were likely distracted by the war effort, but lamented that Calgary’s leading Irish citizens had gotten “cold feet” and failed to plan any celebrations. “If all Irishmen were like the Calgary bunch” closed the writer, then “‘God Save Ireland.’”

The language used by Fitzsimmons in this letter is highly suggestive. By stating that Calgary’s Irish leaders had gotten ‘cold feet,’ he/she was implying that they lacked the courage to publicly celebrate their ethnic heritage. Further, ‘God Save Ireland’ was an explicitly nationalist slogan, associated with the last words of three Irish revolutionaries executed by the British in 1867. In short, Fitzsimmons was calling for an open celebration of Irish identity that did not shy away from nationalist politics. What Fitzsimmons saw as a simple issue, however, was much more complex for the majority of Irish people in Calgary and across Alberta. The often turbulent politics of the Irish homeland, and the campaign for Irish autonomy from Britain, raised difficult questions about what it meant to be Irish in Canada in the early twentieth century. Did public expressions of Irish identity automatically imply support for Irish nationalist politics, or could the two issues be separated? Could a person support Irish nationalism and still affirm loyalty to Canada and, by extension, the British Empire? What was the best way to frame St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in such a way as to affirm devotion to both the Irish homeland and Canada? The stakes of these questions were heightened after 1914, as supporters of Irish nationalism were accused of threatening British imperial unity during a time of war, and again after Easter 1916, when Irish nationalists launched an uprising against British rule in Ireland.

The uneasy relationship between Irish politics, identity and citizenship are reflected in the history of St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in early twentieth century Alberta. The general picture that emerges is of an Irish population that celebrated its ethnic heritage in ways that emphasized loyalty to Ireland, Canada and the British Empire. At particular times, such as the Great War (1914-18), this balancing act proved to be too difficult, and St. Patrick’s Day celebrations largely disappeared from public view. With the emergence of Ireland as an independent state in the early 1920s, Alberta’s Irish once again organized into associations dedicated to celebrating Irish heritage and St .Patrick’s Day soon emerged as an important event in the province.

The population boom of the early 1900s set the stage for significant St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in both Edmonton and Calgary. The 1916 census enumerated 58,068 Irish people in Alberta, of whom approximately 63% were Canadian-born descendants of Irish immigrants; 25% were American-born descendants of Irish immigrants; and 12% were direct immigrants from Ireland (most of whom had arrived in Canada between 1905 and 1914). The diverse origins of the province’s Irish population were reflected in the decorations chosen for the 1908 St. Patrick’s Day banquet at St. Mary’s Hall in Calgary – the platform was decorated with Union Jacks and American flags, over which hung a silk banner with the phrase “Erin go Bragh” (‘Ireland forever’). Toasts were delivered to ‘The King,’ ‘Canada,’ ‘Alberta,’ ‘The United States’ and ‘Ireland’s Future,’ and the event closed with a rousing rendition of “God Save the King,” leaving little doubt that the guests’ vision of ‘Ireland’s Future’ involved its continued association with the British Empire.

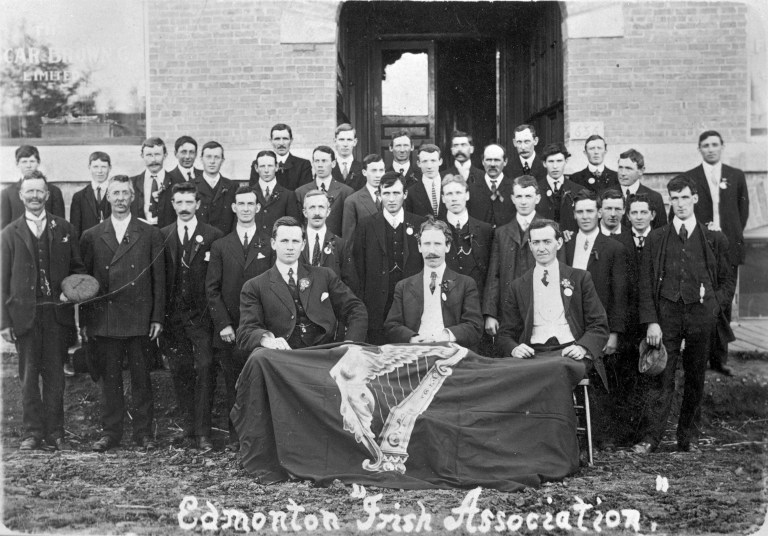

Similar scenes played out in Edmonton, where St. Patrick’s Day events were organized by the highly successful Edmonton Irish Association (EIA). Founded in 1909, the EIA grew to approximately three hundred members by 1911. While primarily a cultural and literary organization, the EIA also sponsored a number of sports teams, including the Irish Canadian Amateur Athletic Association, the Hibernian Football Club and the Irish Canadian Baseball Club. A 1911 profile in the Edmonton Capital stressed that the EIA was “non-political and non-sectarian in character,” and had “from the outset avoided the controversial.” This emphasis echoed the celebrations in Calgary, and indeed reflected a broader pattern across the Prairie West, where explicitly non-political and non-sectarian Irish associations emerged in the early 1900s.

With the worsening Home Rule crisis in Ireland in 1913-1914, it became increasingly difficult for Alberta’s Irish to continue to celebrate their ethnic heritage in an explicitly non-political way. In April 1914, for example, the Edmonton Capital advertised a meeting for those interested in forming an “Imperial British-Irish Association,” suggesting that some of the city’s Irish were no longer satisfied with the Edmonton Irish Association. The outbreak of World War One added another layer of complexity, as the British government put Ireland’s political future on hold for the duration of the war. By the end of 1914, the Edmonton Irish Association had dissolved. Similarly, there is no evidence of any Irish fraternal or benevolent societies in Calgary during the war years. Despite the non-political and non-sectarian nature of pre-war St. Patrick’s Day events, there appears to have been little appetite for Irish organization and celebration during the Great War or the subsequent Irish War of Independence (1919-21). The one exception is a short lived organization called the Irish Glee Club, which emerged in Calgary in 1919 to organize small concerts on St. Patrick’s Day. These events, however, were on a considerably smaller scale than those held prior to World War One.

With the end of the Irish War of Independence and the emergence of the Irish Free State in 1922, the province’s Irish citizens once again organized to publicly celebrate Ireland’s patron saint. Potentially awkward questions about how to reconcile devotion to Ireland and loyalty to Canada and/or Britain faded, as Alberta’s Irish honoured both Irish independence and service to Canada during the Great War. At the 1924 St. Patrick’s Day banquet, for example, the St. Patrick’s Society of Calgary celebrated Irish independence, but placed equal if not greater emphasis on Irish service, “loyalty and allegiance” to Canada during the Great War. The evening’s keynote speaker refused to take a political stance on the divisive civil war in Ireland, commenting only that “the Irish had settled the matter for themselves,” and that whether it had been settled “rightly or wrongly” was irrelevant to him as a Canadian. In place of politics, the new St. Patrick’s Society focused on the celebration of Irish folk culture, arts and crafts. A similar situation emerged in Edmonton, with the founding of the new St. Patrick’s Society of Edmonton in 1927. Like its Calgary counterpart, the society emphasized culture and avoided politics – a safely depoliticized way to honour Ireland. By the mid-1920s, Alberta’s Irish had found a comfortable balance between celebrating their Irish heritage and their contributions to Canadian growth and development.

The history of St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in Alberta thus yields significant insight into the province’s early Irish community. St. Patrick’s Day events represented an important point of intersection between the ethnic community and the rest of the population. It was a holiday intimately associated with Ireland, but widely observed by mainstream society – as such, it offered Irish organizations the opportunity to represent their heritage and their community’s values to a wide and receptive audience. The nature of those celebrations (or the absence of any organized events) is a reflection of what image Irish community leaders wanted to project to the larger population. At times, the tense situation in Ireland complicated those efforts and made it difficult for Alberta’s Irish to publicly embrace and celebrate their ethnic heritage. By the 1920s, such concerns had faded and St. Patrick’s Day celebrations flourished once again.

Written by: Allan Rowe, Historic Places Research Officer.

Further reading:

Cronin, Mike, and Daryl Adair. The Wearing of the Green: A History of St. Patrick’s Day. London & New York: Routledge, 2001.

Where is Rock Creek’s missing rock?

Introducing a guest blog post from Monica Field, one of our colleagues at Historic Sites and Museums.

My story begins in the spring of 2013, when I received a phone call from Hugh Dempsey. He, writing an article for Alberta History, hoped to learn the whereabouts of a rock, a particular rock … a missing rock.

Why did he call me? If you could see my house, my yard, my desk, my office and the view outside my window, you might understand. I work at the Frank Slide Interpretive Centre, and live in a landscape surrounded by rocks of all shapes and sizes. Some follow me. Many, found hither and yon, have fallen into my pockets and been liberated within my office. Others have invaded my home. There, a glacial erratic—it’s a 4,000 kg boulder—anchors my living room to the rocky edge of Rock Creek, a tributary of the Crowsnest River.

I laughed when Hugh told me the story behind the article he was writing. Why? The tale was too unbelievable to be true. But amid its far-fetched elements, there were many profoundly compelling components and juicy aspects of alluring intrigue. I was mesmerized. Within seconds, I was hooked.

If you wish to read the full article, you’ll find it in the summer, 2013 edition of Alberta History. Look for “Count di Castiglione in the West.” Here’s a synopsis:

In 1863, Count Henri Verasis di Castiglione was sent by the King of Italy to explore North America and bring back exotic specimens for a zoo. The Royal Italian Expedition, after traversing the Porcupine Hills, camped at the mouth of Rock Creek near the stream’s confluence with the Crowsnest River. There, not far from Lundbreck Falls, Castiglione and Major Ezeo di Vecchi climbed a nearby ridge and carved their names, the date, and some other information on a slab of sandstone (two feet wide by two and a half feet long).

This was the sandstone slab sought by Dempsey.

Dempsey, following the captivating story of Castiglione, had been trailing the Italian count for more than 40 years. He knew that in 1941, three Smith brothers from Lundbreck had found the inscribed sandstone slab. (Back in 1956 a local writer—and a former neighbor of mine—had heard the story and got the Smith “boys” to take her to the rock. She could read the names and date, but was puzzled over the inscription, which had weathered. No one from the local scene seemed to know more).

Armed with Dempsey’s insights and a picture of the missing rock, I contacted numerous people in an attempt to see if anyone knew of the Smith boys. I also tried to determine if the local writer—who is no longer living—had left insightful notes. I spent hours looking at rocks while exploring the ridges near the mouth of Rock Creek, but struck out on all counts. Castiglione’s inscribed rock seemed to have vanished.

Then I hit pay dirt. It happened when I stopped to talk with an elderly landowner, a man living in close proximity to the missing rock’s described resting place. He told me he’d found the rock years ago and, believing it to be a tombstone, taken it home. Later, regretting his actions, he returned the rock to the place where he’d found it … on a south-facing hillside amid scattered limber pines.

Years passed until one day, in the early 1980s, employees from the Nikka Yuko Japanese Garden in Lethbridge were granted permission from the landowner to excavate limber pines from the same sandstone ridge. When the landowner, returning to examine the site of the tree excavations, looked for the inscribed “tombstone,” he discovered it was gone. (This observation was made roughly three decades ago).

Fast-forward to 2013. I, curious, contacted the Japanese Gardens to see if I could learn more. I received a response indicating that the missing rock couldn’t possibly be in the Japanese Gardens because their rocks had been collected from an area farther west.

I wrote back indicating that, while I knew the bulk of the Japanese Gardens rocks had come from other locations, it seemed likely this particular rock, unusual due to its inscription, could have been collected at the time the Rock Creek limber pines were excavated.

I haven’t found time to visit the Japanese Gardens to see if I might learn more, but I’m mindful that a good sleuth leaves no stone unturned.

The Japanese Gardens are beautiful and well worth a visit. Perhaps, too, the gardens are the key to an elusive sandstone mystery?

My thought: The answer is out there …

Written by: Monica Field, Manager of the Frank Slide Interpretive Centre.

The War Years at (Old) St. Stephen’s College

The faculty and students of Old St. Stephen’s College were not immune to the impact of war. When the First World War broke out in 1914 and the Second in 1939, a number of the college’s own enlisted, while many others assisted on the homefront. The war years were a difficult period for the people of Old St. Stephen’s, but there are several accounts of compassion that emerged during this time. Two people in particular, Nettie Burkholder and Cylo Jackson, showed that those who were affected by the wars were not forgotten.

This article will look at the St. Stephen’s building that converted space to accommodate soldiers, veterans and nurses and the people who stepped in and offered their services when it was needed the most.

(City of Edmonton Archives, EA-63-115).

Throughout most of its history, St. Stephen’s College functioned primarily as a teaching facility and a dormitory for students.[1] This changed during wartime. Injured soldiers returned home from the First World War in large numbers and space for convalescent homes became vital. In 1917, the Military Hospitals Commission set up a hospital within the college to care for some of Alberta’s wounded soldiers. The converted hospital housed up to 300 soldiers and for the next three years, the hospital treated soldiers who were physically injured or afflicted by nervous diseases from the war. According to one veteran, the convalescent hospital was “second to none in the whole of Canada.” Throughout this time, the college continued to operate by offering courses, although much of the classwork was moved to Alberta College North or to other buildings on the University of Alberta campus.

There are stories that indicate the compassion of the college’s educators and show the close ties that formed between students and staff during the wars. Nettie Burkholder was the principal of the Alberta Ladies College, which was located in the north wing of Alberta College South and served as a residence and teaching college for women. During the First World War, she corresponded with the students who went overseas; soldiers stationed overseas sent over 302 letters and cards to Nettie from the battlefront. Nettie also led the college’s initiative to send comfort packages to the soldiers, which were carefully packed with soap and vermin powder, along with treats. The extent of Nettie’s care shows the strong relationships that she maintained with the students of the college and the compassion she demonstrated during wartime indicates her dedication to the school and to the war efforts.[2]

In the early 1920s, the college made the decision to commemorate the students and instructors who served in the Great War with two plaques. The names of more than 80 students and graduates from the Methodist College who enlisted to fight in the war, as well as the eight who died in battle, are inscribed upon it. A second plaque is dedicated to the eight students of Robertson College who lost their lives. These plaques were erected in the college’s chapel where they have remained to the present.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, enrollment and residency declined as more students enlisted in the armed forces and departed for overseas. This created plenty of extra space in the building and St. Stephen’s College offered the use of their northern wing to students in the Canadian Officer Training Corps, who used it as a barracks. The college also leased a portion of the building to the University of Alberta hospital as a dormitory for their nurses. In 1943, Principal Aubrey Stephen Tuttle allowed an additional 45 nurses to room in the building’s west wing, resulting in the number of resident nurses to surpass resident students. Many of the male students who resided at St. Stephen’s College at this time said that there was no issue in sharing the residence with the nurses. D. J. C. Elson, a former Dean of the college, noted that an unusually high number of United Church ministers married nurses around the time of the Second World War and shortly thereafter.

By early 1941, five pupils from the college’s theological program had enlisted in the Second World War. The first student casualty was Royal Canadian Air Force Observer, Flight Sergeant Alexander Granton Patrick. Patrick was killed on January 28, 1942, at the age of 22. Just days later, the college held a memorial service for the fallen soldier in its chapel. The death of a student impacted the members of the college, as shown in the correspondence between Dean Cylo Jackson and Patrick’s mother. Jackson wrote that Patrick was “a kindly lad, upright with a directness in his look and speech which made him engaging…I am very sorry for the loss which the church sustains in his passing.” The Dean’s personal words indicate the relationship that existed between staff and students, which was clearly visible during a time of tragedy.

Throughout both of the wars, when news of casualties reached St. Stephen’s, it affected the students and staff. Wartime proved to be a difficult period, but also illustrated how the people of St. Stephen’s College stepped up and supported their fellow Albertans. The college gave their space, services and whatever else they could to contribute to the war efforts. The stories of compassion from Nettie Burkholder and Cylo Jackson demonstrated how strong the bonds between students and instructors could be. The history of the college during the war years highlight an important era in St. Stephen’s history.

For more information on the history of Old St. Stephen’s College, refer to the previous post: The First Heritage Landmark Built on University Grounds.

Written by: Erin Hoar, Historic Resources Management Branch Officer.

Sources:

Designation File # 132, in the custody of the Historic Resources Management Branch.

Elson, D. J. C. “History Trails: Faith, Labour, and Dreams.” University of Alberta Alumni Association. (Accessed September 23, 2014).

Schoeck, Ellen. I Was There: A Century of Alumni Stories about the University of Alberta, 1906-2006. Edmonton, Canada: The University of Alberta Press, 2006.

Simonson, Gayle. Ever-Widening Circles: A History of St. Stephen’s College. Edmonton, Canada: St. Stephen’s College, 2008.

University of Alberta. “University of Alberta: St. Stephen’s College.” (Accessed September 10, 2014).

University of Alberta. “University of Alberta: University Facilities, Departments, and Faculties During WWII.” (Accessed January 29, 2015).

[1] A note on naming: during the First World War, the institution was known as Alberta College South. ACS and Robertson College were amalgamated and the name St. Stephen’s College was chosen in 1927. It became known as Old St. Stephen’s College in 1952.

[2] Special thanks to Adriana Davies for providing the information on Nettie Burkholder. For further information on Nettie, refer to Davies’ essay “The Gospel of Sacrifice: Lady Principal Nettie Burkholder and Her Boys at the Front” in The Frontier of Patriotism: Alberta and the First World War, edited by Adriana A. Davies and Jeff Keshen, that is soon to be released.

African American Immigration to Alberta

In the early twentieth century, hundreds of African Americans crossed the border in search of land and opportunity in the Prairie West. Many of these immigrants ultimately settled in Alberta, establishing communities such as Wildwood, Keystone (now Breton), Campsie and Amber Valley. The story of these settlers is one of perseverance on both sides of the border – driven out of the United States by persecution and violence, African American migrants had to overcome racist hostility and other barriers on the road to successful settlement in Alberta.

In the minds of many African Americans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Canada was a land of freedom and opportunity. As detailed by historian Sarah-Jane Mathieu, this positive view was rooted in several factors, including Canada’s status as a refuge for runaway slaves in the mid-nineteenth century, and a general perception that African Americans would enjoy fairer treatment under Canadian than American law. This idealization of Canada was heightened by the harsh reality of life for many African Americans, as promises of land and equality in the Reconstruction Era (1865-1877) gave way to segregation, violence and legally-sanctioned discrimination. By the late nineteenth century, many African Americans viewed migration to Canada with increasing favour.

This view of Canada as a haven for African American settlers would prove overly optimistic. A sharp increase in African American immigration to western Canada in 1909-1910 sparked a severe backlash across the region, including several cities in Alberta. The Edmonton Board of Trade prepared a petition calling on the federal government to act against the “serious menace” of ‘negro’ immigration, warning that it would result in “bitter race hatred” if left unchecked. The petition was endorsed by the Boards of Trade for Fort Saskatchewan, Strathcona and Calgary, and was signed by over three thousand citizens of Edmonton, at a time when the city’s population was only twenty-four thousand. Newspapers printed sensationalist stories about the impending “invasion of Negroes,” and while some voices were raised in support of the rights of African American settlers, the federal government came under intense public pressure to take action.

This pressure placed the Government of Canada in a very awkward position. The government was reluctant to openly admit that its immigration policy was dictated by considerations of race (even though that precedent had already been set with the passage of the Chinese Head Tax in 1885). Specifically barring African Americans from entry into Canada at a time when the government was working hard to attract white American homesteaders would create a glaring inconsistency in Canada’s immigration policy. Further, the Canadian government did not want to risk a public dispute with the American government over the issue by explicitly banning the free movement of some of its people across the border.

Instead of enacting an outright ban, the Canadian government took other measures to try and restrict African American immigration. For example, medical examiners stationed at border crossings were instructed to scrutinize African American immigrants for any medical condition that would justify their exclusion, quietly offering a financial bonus to doctors for each African American immigrant rejected at the border. Inspectors were also told to make certain that African American immigrants had adequate cash on hand to successfully homestead – at least two hundred dollars – even though such agents had the power to waive such a requirement for white immigrants. Frustratingly for the federal government, these measures were met with limited success – African American immigrants proved to be healthy, prosperous and well prepared for the challenge that met them at the border. The influx of African American immigrants thus continued through 1910 and 1911.

Facing continued pressure to act, Minister of the Interior Frank Oliver drafted an Order in Council in 1911 that banned “any immigrants belonging to the Negro race” from entering Canada for one year. The Order in Council was approved by Prime Minister Laurier, but the government continued to stall, fearing that enacting an open ban would harm Canadian-American relations at a time when the two governments were negotiating a major trade agreement. Instead, the Canadian government made one final effort to cut off African American immigration at the source by deploying agents to warn potential immigrants about Canada’s harsh and unforgiving climate. The hypocrisy of this strategy was remarkable – at a time when the Canadian government was working hard to assure white Americans that rumours of Canada’s cold climate were exaggerated, other agents were telling potential African American immigrants that Canada was a barren, arctic wasteland. These measures, coupled with the hostile reception already given to African American immigrants, worked to discourage potential migrants and African American immigration to Canada declined after 1911.

To some degree, this legacy of hostility dictated the settlement patterns of those African Americans, about one thousand, who did make it across the border to settle in Alberta in this period. Rather than accepting the best available land as individual homesteaders, they tended to settle in somewhat isolated rural areas where land was plentiful, if somewhat marginal, and they could establish self-sufficient, independent communities. The isolation that allowed such cohesive communities to form also worked against their survival, however, as the children of the first wave of immigrants tended to move on to Alberta’s urban centres in search of better economic opportunity. Of the early settlements, Amber Valley proved to be the most durable, surviving through the Great Depression and World War Two as an important centre of African American settlement in the province.

The story of early twentieth-century African American immigration is an important chapter in the broader history of agricultural settlement in the Canadian west. African Americans sought land and security in Canada at a time when the federal government was eager to attract homesteaders with farming experience. There was little question that the African Americans fleeing Oklahoma possessed the qualifications that the Canadian government prized in immigrants – even the Edmonton Board of Trade’s petition did not deny that “these people may be good farmers or good citizens.” However, the backlash against them, at a time when they comprised up a miniscule proportion of the population, illustrates the extent to which considerations of race entered into immigration policy and what constituted, in the public mind, a desirable settler for Canada. Approximately one thousand African Americans managed to find a home in Alberta between 1909 and 1911, but the public reaction and sustained effort to keep them from entering Canada speaks volumes about the challenges they had to overcome on the road to starting a new life in Alberta.

Written by: Allan Rowe, Historic Places Research Officer.

Sources:

Mathieu, Sarah-Jane. North of the Colour Line: Migration and Black Resistance in Canada, 1870-1955. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Palmer, Howard, and Tamara Palmer, eds. Peoples of Alberta: Portraits of Cultural Diversity. Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1985.

Winks, Robin W. The Blacks in Canada: A History. 2nd ed. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1997.