Written by: Megan Bieraugle

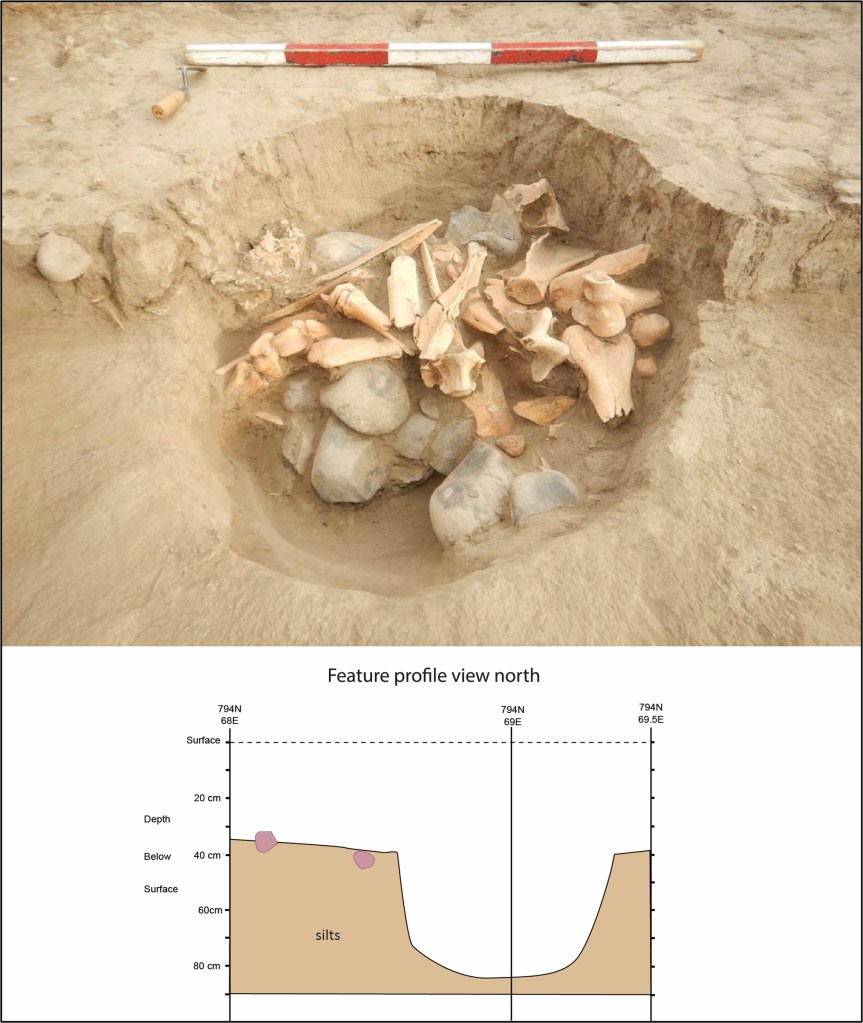

People, dogs and wolves have had long and complex relationships, ranging from cooperation to competition. Alberta’s rich archaeological record includes many canids (mammals including dogs, wolves, coyotes and foxes), and understanding canid age at death can provide insights into their relationships with Indigenous people and how they vary geographically, temporally, and by species.

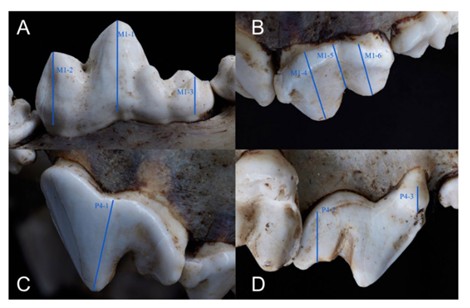

For example, assessments of dog age at death could be informative about how past people cared for their working animals as they aged beyond their prime years. In cases where dogs appear to have been kept primarily for use as food resources, ageing data could reveal how such populations were being managed, with individuals perhaps being slaughtered around 1–2 years of life once they reached full adult body size. Relationships with wolves also might be more fully understood with age-at-death information, particularly in North America, where they are often found in mass bison kill assemblages. Ageing data might reveal if whole packs were killed while scavenging human prey or if primarily young and inexperienced individuals met their fates in such settings. Finally, age-at-death information can be important for assessing aspects of canid life histories, including animals’ rates of tooth loss and fracture and their relationship to diet, but also experiences of degenerative joint disease and trauma. Despite their importance, methods for ageing archaeological dog and wolf remains are relatively limited.